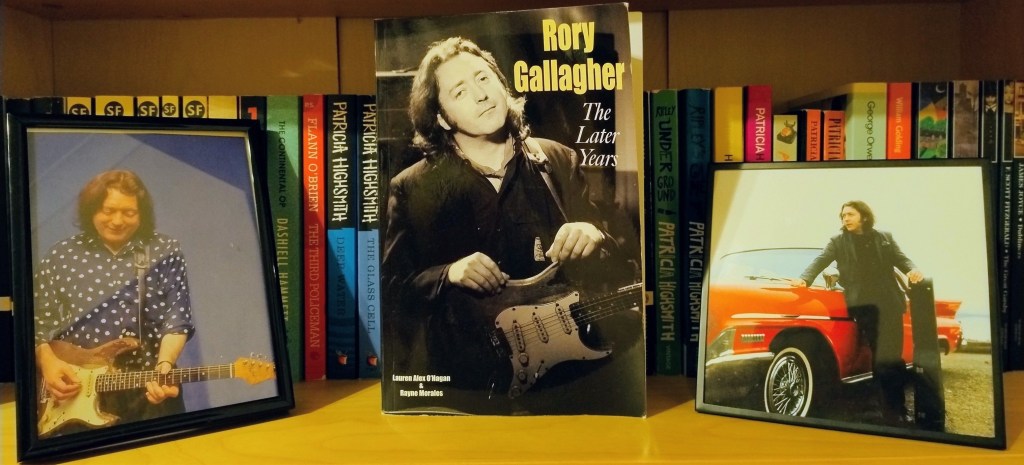

Today marks one year since the publication of Rory Gallagher: The Later Years. The book was truly a labour of love – an attempt to do justice to the final decade of Rory’s life and everything he continued to achieve, despite immense personal and professional challenges. I’m so delighted by how warmly the book has been received by Rory’s family and friends, as well as by fans and the academic community.

On this anniversary, I wanted to share with you an edited version of a conference paper that I delivered earlier this year. It’s much heavier than my usual Rewriting Rory posts, but I hope it might be of interest to those who want to know more about the writing process behind the book and the decisions made along the way.

Introduction

In his final television interview, Rory Gallagher was asked what he ultimately wanted from life. His reply was simple: “to do well for others.” Those five words have stayed with me ever since. They perfectly encapsulate Rory’s humility, his quiet generosity and the deep care he had for those around him.

When Rayne and I embarked upon our book project, Rory Gallagher: The Later Years, we took that quote as our ethical compass. We wanted to do well for Rory. For his family. For his fans. We felt a huge weight of responsibility on our shoulders—not just as academics but, more profoundly, as fans—and that responsibility grew with each passing day.

While much of my previous academic work had focused on portraying the lives of others, this was the first time I would be writing about a famous person. The gravity of the situation was enormous, knowing our words had the potential to affect Rory’s legacy, especially as he continues to accumulate new fans.

But what do you do when those lines between academic and fan blur? When the person you’re writing about isn’t just a subject, but someone whose music has meant the world to you for years? How do you tell their story truthfully and respectfully without crossing personal boundaries? And how do you keep your emotions out of the storytelling or, indeed, do you need to? These were questions we constantly grappled with.

Rory Gallagher: The Later Years was a bold endeavour that built on the success of our Rewriting Rory blog. The idea arose from a deep sense of frustration with previous Rory biographies (in print and visual format) and the way in which they depict his life as a “rise and fall.” This familiar yet incomplete story celebrates Rory’s prolific 1970s output, only to be followed by a supposed downward spiral in the 1980s and early 1990s. This narrative often glosses over—or completely ignores—the rich musical contributions Rory continued to make in those later years.

Yes, he faced serious challenges—health issues, industry pressures and a growing fear of flying—but we felt strongly that these struggles didn’t define him, and certainly didn’t diminish the power of his music. In many accounts, even the circumstances of his long illness and tragic death have been oversimplified, oversensationalised or distorted, feeding myths that do a disservice to who he was as an artist and a person.

As fans with a particular preference for Rory’s later music, we were adamant that there was far more to his story than a man “sinking into oblivion” in the 1980s. He deserved a biography that looked upon his final decade with a much needed fresh and empathetic understanding. We did not want to sugarcoat or shy away from his many struggles, but we wanted to show that his later years should not be defined by them. Ultimately, we sought to reframe discussions and draw attention to all that he continued to achieve musically, despite these struggles, thereby countering many of the previous accounts of his life.

Of course, this kind of project came with its challenges. It was never going to be easy to separate our roles as academics from our identities as fans. In fact, we began to wonder: did we need to separate them at all? Maybe our emotional investment wasn’t a weakness—it could actually be a strength, helping us write with depth and honesty.

But balance was everything. We constantly asked ourselves: How much is too much? What should stay private, and what serves the story? How do we contribute something meaningful to the conversation around Rory’s life while also respecting his legacy and his family’s wishes?

These questions stayed with us throughout the three years it took to write the book. And while we don’t pretend to have all the answers, we hope the end result reflects the care, thought and deep admiration that shaped every word.

Double Positionalities and Fannish Sensibilities

Writing a biography always involves tough choices. But when you’re both an academic and a devoted fan of the person you’re writing about, those choices get even tougher. In our case, writing Rory Gallagher: The Later Years meant walking a very fine line—between truth and loyalty, between private respect and public record, between academic rigour and personal emotion.

Biographical writing comes with its own set of moral obligations. As sociologist Jerome G. Manis reminds us, academic work is bound to a “dictum of truth,” which must be upheld through careful documentation, interpretation and ethical responsibility. But Manis also warns against letting ethics become a cover for self-interest—or a form of censorship. These tensions played out daily in our research.

We wanted to tell Rory’s story truthfully—but also respectfully. We aimed to honour his legacy, without turning our admiration into censorship. And we constantly wrestled with how much to share about his private life. Was it essential to understanding his music? Or did it cross a line?

Interestingly, fan communities operate with their own kind of ethical framework too. Henry Jenkins describes this as a “moral economy”—a shared understanding of what’s valued, what’s taboo and how fans interact emotionally and culturally with the figures they admire. As we saw it, we weren’t caught between two conflicting roles, but rather trying to find where they could align.

Media scholar Matt Hills argues that the roles of fan and academic can coexist “positively and productively.” The fan brings passion and depth of knowledge; the academic brings critical perspective. Scholars like Cécile Cristofari and Matthieu Guitton go further, suggesting that the boundary between these roles is often artificial. Knowledge production, structure and dissemination happen in both worlds—just with different languages and expectations.

That said, academia still tends to value detachment. Kristina Busse and Karen Hellekson warn that emotional proximity can devalue research. But others, like Roger Silverstone, offer a more nuanced view. He introduces the idea of “proper distance”—not cold detachment, but a space for imagination, empathy and ethical judgment. It’s about creating room for the “other” while maintaining a duty of care.

This “double positionality” we occupied—fan and academic—has become increasingly central to fandom studies, particularly through the lens of affect theory. Sara Ahmed’s work was especially influential for us. She argues that emotions aren’t just personal responses—they’re cultural and social practices that shape how we interpret the world. “Theory can do more the closer it gets to the skin,” she writes. For us, that meant acknowledging our emotional connection to Rory not as a liability, but as a resource.

An affective approach to biography asks not just what we know, but how and why we know it—and how our feelings inform those processes. Traditionally, academic writing hides the struggle behind tidy conclusions. But affect theory invites us to reflect on those tensions and use them productively.

Many terms have been used to describe this double positionality, such as scholar-fans, fan-scholars, aca-fans, fan researchers and fan-experts, but I intentionally choose the term “academic fangirl” to describe myself in order to take back ownership of a derogatory term and rid it of its negative aspects. As Rosemary Hill has shown, women in rock and metal fandoms are often written off as “groupies,” while their deeper, more personal fan practices—intimate listening, emotional responses, everyday acts of fandom—are overlooked. Hill’s work expands the idea of fandom from something performative to something phenomenological: a way of being in the world. Reappropriating the “fangirl” label is about pushing back against those hierarchies. It’s also about valuing the affective, emotional and situated knowledge that often gets dismissed in academic discourse.

Of course, our specific positionalities—gender, age, nationality, language, mental health experiences, digital literacy—all shaped how we approached Rory’s story. In contrast to previous biographies, largely written by older male journalists, our background opened up space for new perspectives—particularly around wellbeing, technology and the emotional resonance of his later music.

We also drew heavily on the “fannish methodology” proposed by Sophie Hansal and Marianne Gunderson, which helped guide our work:

- Critically reflect upon and question the dichotomous and oppositional conceptualisation of emotion and rationality and its hegemony in academic thought (i.e. use emotion as a resource)

- Accept that academics write from a specific position, where they oftentimes are both researchers and fans, both participants and observers (i.e. embrace and critically reflect upon your double positionality)

- Employ a collectivist and community-based approach based on the premises of cooperation and reciprocity (i.e. seek to add value to both academia and fandom)

- Be irreverent towards authority and canons and bring together resources in new and unexpected ways (i.e. move beyond disciplines and engage in ‘textual poaching’)

This approach allowed us to write a biography that was both emotionally engaged and intellectually rigorous—one that respected Rory’s complexity without reducing him to myth or tragedy.

Ultimately, being an academic fangirl wasn’t a liability—it was the very thing that helped us see Rory’s later years more clearly and tell a story that had yet to be told.

Establishing Boundaries

We were clear from the start that, in telling the story of Rory’s final decade, we didn’t want to fall into the familiar traps of pathography or hagiography. That is, we didn’t want to dwell morbidly on the difficulties Rory faced, nor did we want to present the final years of his life with undue reverence. Instead, we aimed for something more grounded: a realistic and non-judgemental portrayal that put Rory’s career in the foreground, while still acknowledging the personal and physical challenges he faced.

The question, of course, was how to begin.

Over many long Zoom sessions, we brainstormed what a book titled Rory Gallagher: The Later Years should include. We eventually settled on 19 chapters arranged across four sections:

- Part 1 – In the Studio

- Part 2 – On the Road (1985–1991)

- Part 3 – On the Road (1992–1995)

- Part 4 – Ireland

These would be framed by an Introduction, an Interlude and a Conclusion. Unlike previous Rory biographies, we opted for an essay-style format, designed to disrupt conventional chronologies and invite readers to explore the book non-linearly—gravitating to chapters that piqued their curiosity. In another conscious departure from tradition, we chose not to end with Rory’s death, but with his posthumous resurgence—his “rise and rise” in the 21st century among a younger fanbase. This decision was part of our broader challenge to the “rise and fall” narrative that dominates many artist biographies.

One of our biggest editorial dilemmas was whether to include Rory’s final tour in January 1995—a brief run of dates in the Netherlands that was cut short due to his declining health. This tour has long been shrouded in discomfort and speculation, with persistent (and unsubstantiated) claims that Rory collapsed onstage during his final concert. Contemporary commentary on the tour has been overwhelmingly negative; even Rory’s brother and manager, Dónal, noted in a 2000 interview with Aardschok that “it’s painful that such a dedicated artist had to say goodbye to the stage in this way.” We debated: would including this chapter do a disservice to Rory’s musical legacy? Or would omitting it erase a key moment in his career, especially given that his live performances were central to his identity as a musician?

Ultimately, it was a conversation with keyboardist Kevin Breslin of Energy Orchard that shifted our thinking. Kevin offered an unexpectedly positive recollection of Rory’s energy and presence onstage on that final tour:

“His energy level onstage was off the charts, and that’s one thing that will always stick with me… his whole attitude to music and performance was definitely just Rory, and it was just so positive. When we met up on the tour, he came round backstage, down the corridor, and he was just glowing. It was terrific to see him like that… you know, when he walked into a room, he just lifted the whole room.

[When] Rory [went onstage], he just opened up with this song, and I was just shocked. He was playing these notes that I didn’t think existed. I was like, ‘Where did that come from?’ I turned to the [stage manager], and he said, ‘I don’t know what it is, but he hasn’t been playing like that until you guys arrived’.

There was a guy on crutches at the front of the stage, and [Rory] reached out and asked him for one of his crutches, and he played a solo using his crutch. It was incredible. Not one note was bent slightly wrong; it was just perfect. And then he gave the crutch back to the guy, and there was just this glow coming from him.”

This testimony didn’t just challenge our assumptions about Rory’s final tour; it reshaped our understanding of how to tell his story more broadly. It reminded us to look beyond simple binaries of “good” and “bad” and to seek out moments of light within the shadows. It also reinforced our desire to centre the voices of those who knew Rory best—fellow musicians, crew and fans—as valid sources of knowledge and meaning.

To this end, we sought an inclusive and participatory relationship approach. Drawing on friendships within Rory’s online fan communities (particularly on Instagram and Facebook), we asked what had felt missing in earlier biographies and what readers wanted to see done differently. We also combed through Amazon and Goodreads reviews to identify common frustrations. From this, seven recurring points emerged:

- A lack of focus on Rory’s instruments, gear and technique

- A reliance on archival press quotes rather than new interviews

- Neglect of Rory’s personal life

- Minimal coverage of his later musical achievements

- Simplistic treatment of his complex personality and health challenges

- Sparse information on other members of Rory’s band

- Little insight into what truly motivated Rory as a musician

By its very design, our book addressed point 4, with point 5 serving as a core motivation for the entire project. But even before this community feedback, we had already committed to highlighting the final Rory Gallagher Band (point 6), exploring Rory’s gear and playing style (point 1), and conducting new interviews (point 2). This feedback confirmed we were on the right track—and helped us refine our approach. What motivated Rory as a musician was a little more abstract (point 7), yet we endeavoured to present this as a thread running throughout the book and feeding into our presentation of notable events in his final decade and their personal significance to him as a musician.

The most ethically complex point was Rory’s personal life (point 3), given that he was an extremely private individual. Indeed, an RTÉ producer I interviewed stated how he had once wanted to make a documentary about Rory, but there were certain areas that his brother Dónal was protecting so that “we remember the right things,” leading the idea to be abandoned. Among fans, opinions varied: some wanted a glimpse of the man behind the guitar; others felt strongly that his private life should remain private. Some were comfortable with us quoting Dónal’s public stories, but not venturing further. Most simply wished to understand more about Rory’s non-musical interests because they felt that he was presented as “too one-dimensional” or to clarify the circumstances of his illness and death.

It is well documented that Rory prioritised his career and musical aspirations over personal relationships (“He lost out. He was dedicated. It was a vocation for him, so everything else was set aside,” said Dónal in a 1997 documentary). Nonetheless, it was notable that all of the fans we spoke to wanted us to stay clear of the topic out of respect for Rory’s privacy and to avoid any speculations about his life choices.

Ultimately, we chose a restrained path: we decided that we would not include anything in the book that Dónal himself had not explicitly referenced before and only focus on elements of Rory’s personal life that were relevant to our arguments. To provide a robust structure for this decision-making process, Geoffrey Warnock’s four virtues were consulted:

1. Non-maleficence: obligation to refrain from unjustifiably harming the person

2. Beneficence: obligation to refrain from inflicting emotional harm on the person

3. Fairness: obligation to determine what is morally right and wrong

4. Non-deception: obligation not to intentionally provide inaccurate or false information to subjects

These four virtues, along with the aforementioned fannish methodology, formed the theoretical basis of the biography, ensuring that everything written contributed to our broader vision rather than detracted from it.

Before approaching publishing houses with our book proposal, we decided to speak directly with the Gallagher estate, specifically Dónal Gallagher and his son Daniel. As much as we wanted to pursue our project, we were resolute that we did want to do so without their blessing. We were also aware that some previous Rory biographers had failed to consult the estate, which had led to negative press and strained relationships.

Fortunately, both Dónal and Daniel were already familiar with and complimentary of our work with Rewriting Rory, as well as my previous academic contributions on Rory. Our blogs and papers had even been reposted across the official Rory Gallagher social media platforms, so we hoped that they would see that our intentions were honourable.

We shared our book proposal and introductory chapter with them and were delighted to receive a positive response. We vowed to keep them updated every step of the way and factcheck important information with them. As the 1985-1995 period is so poorly documented with large gaps in the narrative, having this line of contact was extremely important to the integrity of the biography.

In January 2023, our book proposal was picked up by WP Wymer, and we set about writing Rory Gallagher: The Later Years.

Dealing with Unjustified Exposure and Emotional Distress

In her thesis Ethics of Biography: What Moral Considerations Do We Owe the Dead?, Helen Syron discusses the “feeling of unjustified exposure” that arose when reading a particular biography. This discomfort prompted her to ask: “does knowledge always justify exposure?”

Syron’s question stayed with us throughout the writing of Rory Gallagher: The Later Years as we conducted hundreds of interviews with Rory’s family members and friends, as well as fellow musicians, photographers, journalists and fans. We were privileged to hear first-hand accounts of Rory’s life, but this did not give us the right to share everything that we learnt.

We had already experienced that same discomfort Syron describes when reading a previous Rory biography, which included transcripts from personal conversations that—unbeknown to Rory—had been secretly recorded by a close friend. In these conversations, Rory confesses his struggles to cope mentally, the stunted pauses and repetition emphasising his clear distress. Reading them felt like stepping into a room we weren’t meant to enter. We did not want our book to violate Rory’s privacy in the same way.

One of our most ethically complex interviews was with Toine von Berlo, who had served as Rory’s chauffeur during his final tour in the Netherlands in January 1995. Toine had spent three entire days with Rory leading up to and following his final concert in Rotterdam. Given the amount of misinformation and rumours about this concert, both in the press and fan community, his insights were invaluable in clearing up some of the mysteries.

The interview lasted over three hours and it’s something that I will never forget. Some of the things I learnt were extremely difficult to hear and underscored just how incredibly unwell Rory was at this stage in his life. At one point in our interview, I openly cried, and the weight of what I had learnt played around in my head for weeks after. I had long discussions with Rayne on how best to present this conversation in our book. On the one hand, Toine’s testimony offered much-needed clarity and could bring comfort and closure to fans. On the other, we had to ask ourselves, once again, “Does knowledge always justify exposure?”

At crucial moments like this, I turned to a broader network of trusted friends in the Rory Gallagher Instagram community. Without revealing the discreet details of the interview, I gauged their opinion on what they might expect from a chapter on Gallagher’s final tour and where to draw the line on what not to include. I also sought counsel from experienced research colleagues at my university, including an academic capacity-building coach. Interestingly, the latter also shared a personal anecdote of once reading a biography and, like Syron, being alarmed that the author had unnecessarily revealed too much, fulfilling their own individual agenda rather than that of the subject of the biography. Finally, I brought the query to an all-female academic support group of which I am a member.

Taking all their views into account, we decided that, rather than form a particular argument (as our other chapters did), this chapter would simply be a presentation of facts, with insights from Toine only included when directly relevant to our narrative. There were things that we decided point-blank not to include, while there were others that we included and then later scrapped. Of all the chapters in our book, this was the one over which we agonised the most and subjected to the most edits.

Adhering to Warnock’s four virtues and in line with our affective approach, we wore our heart on our sleeves, telling readers of the challenges we faced and reassuring them upfront of our intentions. As Rayne wrote in the chapter’s introduction:

“When planning out this book, we often debated on the inclusion of this chapter and, if included, what would the purpose be? Occasionally, our opinion veered towards discarding the idea—if, indeed, there even was an idea to share. Nevertheless, we could not claim to write a book about the final decade of Gallagher’s life without including the final year—no matter how brief. We do not write this chapter to put Gallagher’s fragile wellbeing on a pedestal, dissect the contents and critique. We do not present our research as a disrespectful gesture towards a man clearly plummeting deeper into the murky gulf of depression. We simply present the stories and, as best possible, the facts of Rory Gallagher on his short Dutch tour in 1995. As we gathered research for this chapter, we came across multiple versions of Gallagher’s ‘collapse’ in Rotterdam, ultimately challenging our perceptions of how the concert (and the tour overall) unfolded. As such, we hope the reader can be guided by our balanced approach to question the many speculations associated with Gallagher’s final tour.”

Naturally, interviews like the one with Toine could be emotionally draining. In fact, when I set out on this journey, I did not anticipate how much of an emotional toll this project would take on me. There were so many grown men who burst into tears during conversations and it was hard to know how to respond. Too often, I found my own emotions getting the better of me and I joined them in tears, especially if their stories resonated with my own personal life experiences. Often, their words lingered in my mind long after the conversations were over, making it hard to disconnect at times. After several interviews, I decided that putting a self-care regime in place was necessary to protect my own wellbeing and, ultimately, to ensure the success of the project.

Usually, I would turn to Rory’s music for comfort, but when his life occupied every hour of my working day, I wondered if it would be wise to listen to his albums during my downtime. I found a middle ground by turning to music from his 1970s period; this offered enough distance to detach myself from the work yet provided me with the comfort and resilience I so desperately needed. As emails and messages from contributors could come in at any time of day, I also stopped checking my phone after a certain time so that the book was not actively in my mind when I went to bed. The three aforementioned groups (the Instagram community, work colleagues and the academic support group) all acted as safe spaces, where I could vent, seek advice or simply escape for a while.

To process my emotional responses, I started a reflective diary, which allowed me to document my thoughts and understand where my emotions came from. This, in turn, helped me channel these feelings into the book itself. Additionally, I turned to autoethnography to explore my own journey as both a Rory fan and an academic. This led to two publications: a personal account of my involvement in the Rory Gallagher Instagram community and a reflection on a ‘pilgrimage’ I made to Rory’s hometown of Cork.

In addition to the emotional challenges of the interviews, another hurdle was psyching myself up to listen to a bootleg from which I had deliberately shied away for many years. The bootleg was recorded at a now-infamous concert that Rory gave at the Town & Country Club in October 1992. An adverse effect to his prescribed medication meant that he appeared intoxicated onstage and was unable to perform properly, eventually being escorted off by his brother Dónal following jeers and boos from an angry crowd. We wanted to address this gig head on in our book because it is an anomaly that is responsible for many of the negative attitudes towards the final years of Gallagher’s career. But to do so, I first had to bring myself to listen to it.

The recording sat on my desktop unopened for weeks. After several months, I finally found the strength to open the file, but my finger hovered over the play button, unable to go through with it. More weeks passed until I eventually hit play, listening to the full 45 minutes (with pauses along the way) and documenting in my diary how each part made me feel. It was just as hard as I had expected. When discussing the Town & Country Club in our book, I felt it would be dishonest not to describe my struggle to readers. After all, an affective approach must get close to the skin. “‘Dónal, take him off, for fuck’s sake’. Seven little words that make my skin crawl and blood boil every time I hear them,” I wrote, “It is heartwrenching and extremely tough to listen to, especially for a diehard fan like me.”

I had a similar experience when psyching myself up to listen to a radio interview that Rory did in 1993. He sounds distressed, anxious, confused even. Again, I felt it was important to convey my discomfort to readers, explaining how the interview made me feel, and reflecting on how deeply these moments affected me personally: “It is an interview that is rather uncomfortable for me to listen to, with Gallagher clearly exhausted and audibly distressed when the topic turns to personal matters and his health.”

To process both experiences, I found myself turning to poetry as an outlet. It was deeply cathartic and offered me “an attempt at self-healing through self-empathy.” I also used social media to undertake this process of “re-storying,” using my Rory fan account to share more heat of the moment reflections.

Not all experiences were distressing, however, and along the way, we encountered much joy and optimism. It was important for us to incorporate these emotions into our affective approach too. An early interview with violinist Roberto Manes, for example, still remains fresh in my mind as he was such a warm, friendly and kind person. When writing about Roberto in the biography, we offered these more personal reflections on his character. Likewise, we acknowledged—when appropriate in the text—the sheer happiness on a personal level that certain concerts gave us. In the part of the book that covers Rory’s Australian tours, Rayne—as an Australian—also brought in her own personal perspective. We were also deeply touched by the support of those close to Rory like his cousin Jim Roche and music-photojournalist and friend Bob Hewitt. We reflected directly on their willingness to provide personal anecdotes and photographs in our narrative.

As a multilinguist, I found that accessing non-English resources was extremely valuable, offering insights into different interpretations and perspectives on Rory’s career beyond the Anglo press. This helped me balance accounts of his life and trace the reasons behind negative portrayals, as outlined in the introduction:

“Overall, when we look back over what has been written to date about Gallagher, we see that there are several components at the root of this ‘rise and fall’ narrative: the (in)visibility of Gallagher’s final decade in most publications to date and, consequently, a lack of information about his achievements; an overwhelming focus on Gallagher’s physical appearance, leading to misconceptions about his ability to perform; ‘fuzzy’ knowledge about Gallagher’s illness and death; and damage caused by shoddy journalism—both within Gallagher’s lifetime and posthumously—that often relies on selective citations, calculated framing or Irish stereotyping to perpetuate certain discourses, which have subsequently been spread by social media.”

Conclusion

At its heart, Rory Gallagher: The Later Years was a labour of love — a love for Rory and a love for his music. We felt that we owed an immense debt to Rory for his impact on our lives, but we equally owed a great deal to his family, who entrusted us with this task, and to his fellow fans—often the most passionate critics and staunchest guardians of his legacy. Our goal was to give Rory the story he deserved: one that invites a reappraisal of his final decade, while staying true to our academic integrity and professionalism.

Our approach to biography was not as a static, authoritative account of Rory’s life, but as a dynamic, emotionally engaged and ethically conscious form of storytelling. For us, biography is as much about responsibility as it is about representation. Its purpose is not merely to tell a life, but to care for it—to understand rather than expose, to humanise rather than mythologise. We also saw biography as an explicitly dialogic and community-oriented practice, one that values the perspectives of Rory’s family, friends, fellow musicians and fans as part of a broader, collective process of truth-making, rather than relying on an omniscient narrative voice.

By adopting an affective approach, we treated our emotions not as obstacles but as valuable resources. We engaged in continual critical reflection, allowing our positionality to inform—rather than obscure—our work. At the same time, we held a clear belief that academia and fandom are not mutually exclusive, but can meaningfully enrich one another. That you can be an “academic fangirl” and still write with rigour, clarity, and integrity.

And if Rory’s wish was to “do well for others,” then this book — in all its joy and sorrow, labour and love — is our way of trying to do well by him.

If you have not yet purchased a copy of Rory Gallagher: The Later Years and would like to do so, then please visit WP Wymer or Amazon.

Leave a reply to Eamon Maguire Cancel reply