Back in November 2021, the Rewriting Rory blog was launched, aimed at shining a positive light on the later years of Rory’s career – years that have often been overlooked or misrepresented in previous accounts of his life.

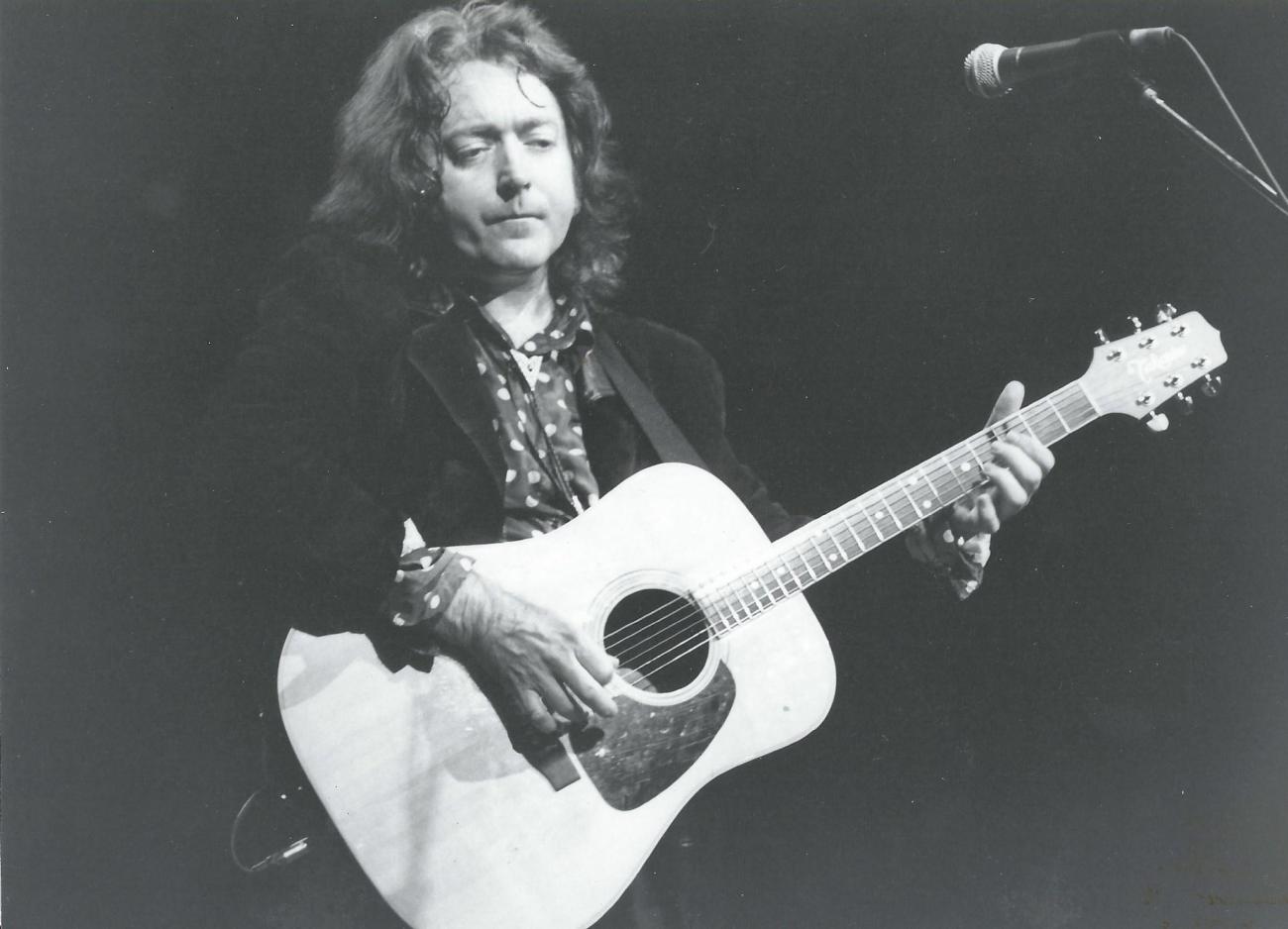

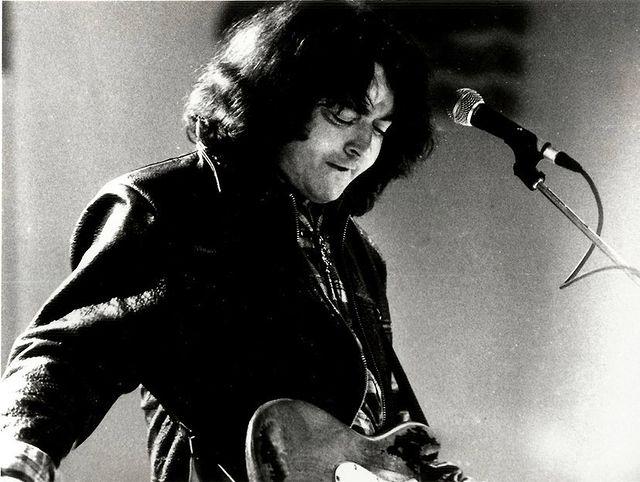

Now, almost three years later, I am thrilled to be celebrating the release of Rory Gallagher: The Later Years today, compiled from almost 200 new interviews and extensive archival research across 15 countries.

If you haven’t yet purchased a copy, you can do so through Wymer’s website.

The book seeks to bridge the popular and the academic. It serves as a general interest music book intended to resonate with both long-time Rory fans and those new to his work, as well as contributing to the fields of Irish musicology and cultural history, where Rory’s influence remains neglected.

In line with this mission, I was recently interviewed about the book by two prominent representatives of each area: MJ Steel Collins, poet, publisher and self-confessed Rory enthusiast, and Professor Gerry Smyth from Liverpool John Moores University. To celebrate the book’s release, I am sharing edited transcripts of the two interviews below. Hope you enjoy them!

Interview with MJ Steel Collins

MJ Steel Collins (hereafter, MJSC): Why did you start the Rewriting Rory blog, and subsequently, the book?

Lauren Alex O’Hagan (hereafter, LAO): It might sound a bit strange, but the Rewriting Rory blog was actually born out of great frustration! For many years, I’d been a member of various Rory groups on Facebook and was dismayed to see such negative comments whenever photos from his final decade were shared. What upset me most was how these comments were often focused more on his appearance than his music, with countless rumours circulating about his health and ‘problems’ with alcohol, etc. I often found myself acting like a bit of a keyboard warrior, rushing in to defend Rory, but eventually, I decided that I wanted to do something more meaningful and proactive.

I ended up putting together a long piece of writing expressing all my frustrations and shared it with my friend Rayne – whom I had met through the Rory Instagram fan community. At the time, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with it – I just needed to get some things off my chest – but Rayne really liked it and encouraged me to start a blog about Rory’s final years. I asked if she’d join me on the venture, and in November 2021, we launched the Rewriting Rory blog with that piece.

To our surprise, things took off quickly as we found that many others also shared our frustrations. We began developing regular blog posts and, as you know, our website grew, along with our presence on social media. Soon, it became clear that the next logical step was a book. We had gathered so much new information from interviews and archives that we felt it deserved to be shared in a more permanent form to showcase all the amazing things that Rory was still doing.

After drafting an introduction and a book proposal with chapter outlines, we sent them to Dónal and Daniel Gallagher, as we didn’t want to proceed without their approval. Once they gave us the green light, we reached out to publishers and were delighted when Wymer immediately picked it up. And now, here is Rory Gallagher: The Later Years, finally out in the world!

MJSC: What do you want people to take away from the book?

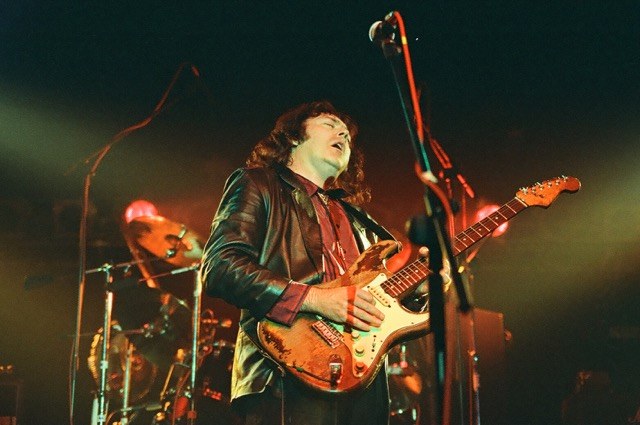

LAO: That’s a big question! I guess, above all, I want people to see that Rory remained an incredible musician and never ‘lost it’, as some have claimed. To me, he only got better and better. His musicianship and songwriting evolved, he was exploring all kinds of interesting musical avenues and had so many exciting plans for the future. And all of this was in the face of significant personal challenges, from his worsening physical and mental health to the departure of long-term band members Gerry McAvoy and Brendan O’Neill, and everything in between! It’s truly remarkable.

I hope even long-term fans will learn something new about Rory from this book. There are so many musical achievements in his later years that aren’t discussed in other works because they tend to focus heavily on his health problems during this period. For example, his civic reception with the Lord Mayor of Cork in 1992, his role in the Nelson Mandela birthday concert in Dublin in 1988, his collaboration and friendship with Roberto Manes… and so much more!

Ultimately, I want people to stop depicting Rory’s life as a cliched rise and fall and instead view it as a continual rise – one that is still ongoing today with his growing young fanbase.

MJSC: What do you think the book will offer to the overall Rory narrative?

LAO: It might be a big ask, but I truly hope that it will encourage people, both within and beyond the fan community, to think differently about Rory’s later years and view them more positively in terms of his musical achievements. Yes, of course, we can’t change the sad ending to his story, but we need to shift the focus. It’s not about denying or ignoring his struggles; on the contrary, it’s about framing them within the context of all he continued to achieve against the odds, which deserves immense respect.

Dónal has never shied away from discussing Rory’s struggles, and he seems to have become even more candid in recent years, especially if you watch the latest Rory documentary and Dónal’s interview with Dave Fanning at Ballyshannon. I think it’s so important to have these open conversations today as many musicians struggle with their mental health and wellbeing. I remember you and I had this very conversation last year after Lewis Capaldi’s Glastonbury performance and how fans’ reactions differed compared to what happened to Rory at the Town & Country Club in 1992.

Going back to Rory’s music, during research for this book, I was amazed at how many people made negative comments about Rory’s later years, yet hadn’t actually listened to Defender or Fresh Evidence, or who simply refused to watch his later concerts. I think the Gallagher estate’s decision to release All Around Man in 2023 [a double live album compiling Rory’s two 1990 concerts at the Town & Country Club in London] really set us on the right path as it demonstrated his continued musical greatness and surprised a lot of people. It made me so happy to see positive comments about the album in the fan community and the music press. I hope the book continues to shift perceptions in this way.

MJSC: Who are the key players in your view in Rory’s final decade?

LAO: Well, of course, you can’t talk about key players in Rory’s life without mentioning his brother Dónal – there for him throughout his career, not just in the final decade. In those last years, Dónal assumed so many additional responsibilities for Rory under very difficult circumstances that really couldn’t have been easy. I can’t speak highly enough of him. On the family side, I must also mention Rory’s mother, Monica, who was always a solid support and a source of solace for him back in Ireland.

Then, there’s the wonderful Mark Feltham, not just for his musical contributions to the band, but also as a friend who stood by Rory until the end, even being at his side when he passed away. The new band members, David Levy and Richard Newman, also deserve recognition for injecting Rory’s music with a new burst of youthful energy. They also really looked out for him onstage if you watch those later concerts.

Two other individuals who haven’t been spoken about much before are Shu Tomioka and Roberto Manes. Rory formed friendships with both men in his later years in London. They truly are lovely people who made a positive impact on his life at a difficult time, and Rayne and I have such fond memories of speaking with them throughout the writing of this book.

MJSC: What is Rory Gallagher’s legacy?

LAO: That’s another big question, MJ, which we talk about in depth in the final chapter of the book. Well, I think it’s safe to say that Rory’s legacy is definitely in good hands, what with Daniel largely taking the helm from Dónal and putting out some excellent releases in recent years.

I think we’re at a really exciting time as Rory fans because his fanbase continues to grow, particularly amongst young people who have discovered him thanks to YouTube, Spotify and other platforms. There’s so much on the horizon like the new BBC release coming next week, the Marquee concert in Cork for his 30th anniversary next year, the Cork Person of the Year award and a statue outside the Ulster Hall in Belfast. People are also starting to appreciate Rory beyond his undeniable guitar virtuosity and live performances, and reconsidering his songwriting, studio work and pioneering approach to the blues. From the academic side, I hope to make my own contribution by continuing to research areas of his life that have been previously overlooked or by coming at them from new angles based on my own background in sociolinguistics and media and communication studies.

And away from music, I want to highlight Rory’s legacy as a thoroughly decent human being—a true role model, gentleman and example to all. That’s part of the reason he is so deeply loved and sorely missed. I quote it all the time, but I just love what Gordon Morris once said about him: “If you were to write down every attribute you could ever think of to make up the perfect person, you would probably look at the list and think that nobody could quite match up. But in fact, you would have listed something only just approaching the gentle man that was Rory Gallagher.”

MJSC: Where do you go from here as a Rory fan and researcher?

LAO: [laughs] My work is never done when it comes to Rory! I have so many more plans and ideas on the horizon, and I’m very grateful that my job as a research fellow at the Open University allows me to explore them professionally. I’m just about to begin a six-month pilot project focusing on music memorabilia and its role in parasocial relationships, particularly in navigating death and memorialising life. I’m using Rory as a case study, so readers, expect to hear from me soon as I reach out for interviews!

Depending on the findings, I then plan to apply for funding for a larger three-year project that will examine Rory’s significance specifically in the context of Northern Ireland through a material culture lens. The recently acquired Carol Clerk scrapbooks at the Oh Yeah! Music Centre sparked this idea. You know, they include the wrapper of chewing gum she offered Rory during his concert at the Ulster Hall in 1972!

Outside of my research, I’m heavily involved in Sheena Crowley’s campaign to bring the Strat home to Cork. That has been taking up a lot of my time lately! Who knows what will unfold on 17 October, but I’ll definitely be there! I also plan to continue my work with Rewriting Rory and maintain our social media presence.

Interview with Professor Gerry Smyth

Gerry Smyth (hereafter, GS): Can you expand upon the ‘rise and fall narrative’ as applied to popular music, especially the broad family of rock ‘n’ roll?

LAO: I think the rise and fall narrative is a recurring trope in popular music, particularly in rock ‘n’ roll. You only have to look at recent biopics like those about Elvis Presley, Elton John and Amy Winehouse to see it. Such stories typically follow a similar arc of a person from humble beginnings overcoming obstacles to pursue their dreams, achieving breakthrough success and fame, and then facing some kind of struggle or challenge, be it personal issues, substance abuse or public scandal, that ultimately leads to their decline or obscurity. Sometimes, these narratives conclude with the artist finding redemption through a comeback, while other times they end tragically, with the artist only receiving posthumous approval. While these types of stories seem to resonate with audiences, I think they oversimplify the complexities of an artist’s life and reduces them to clichés. I guess that is the key principle behind Rory Gallagher: The Later Years – to provide a nuanced account of Rory’s life that does not fit neatly into this ‘rise and fall’ narrative. We try to show that his story is rich and multifaceted, focusing on the many musical achievements in his latter years that have often been disregarded.

GS: How can we resolve the tension between Rory’s hesitancy regarding contemporary music trends – and much of the time his disdain for those trends – and his anxieties relating to his ‘outsider’ status?

LAO: Yes, this is definitely an interesting tension. As you rightly say, Rory was always reluctant to conform to trends; he famously avoided releasing singles, appearing on Top of the Pops and always stayed true to the music he wanted to play. However, in his final decade, he became more vocal about his feelings of being overlooked. I do believe this was partially a reflection of his worsening depression at the time. There are some interviews where he expressed real feelings of hopelessness, even suggesting that he might as well give everything up and go fishing, as he found no satisfaction in music anymore. Certainly, the blues ‘revival’ of the 1990s was upsetting for him, especially seeing albums like Gary Moore’s Still Got the Blues have great success when he had remained loyal to that music throughout his career.

I think, after years in the industry, Rory simply wanted some form of acknowledgment for his musical contributions. I don’t mean in terms of fortune, fame or even popularity; rather, he sought recognition beyond his guitar work. He wanted to be seen not just as resilient or loyal to the blues, but as an artist who pushed its boundaries and constantly evolved. It was also important for him to have his contributions as a songwriter and studio artist acknowledged, rather than being viewed solely as someone who used lyrics as a shortcut to long solos. Additionally, he hoped to be recognised as a collaborator and champion of younger musicians.

I think we try to do this in the book by emphasising these aspects of Rory’s career, while also focusing on his legacy and how he is viewed today because, unfortunately, much of this recognition did not come during his lifetime. However, saying that, there are some accolades from his final decade that often go unrecognised that we do mention, such as his civic reception at Cork City Hall in 1992 and the Fender/Arbiter Hall of Fame Award he received that same year.

GS: In the book, you say that later negative reviews prompt us to consider the extent to which contemporary opinions on Rory’s later recordings are influenced by hindsight rather than actual album quality. Isn’t the ‘quality’ of all music actually an intensely subjective issue? Where is the court in which the ‘quality’ of Rory’s music will be (or could be) finally judged?

LAO: Yes, I completely agree that the ‘quality’ of music is highly subjective, and fans will naturally have their favourite periods in an artist’s career. My fundamental concern – and the reason we first set up Rewriting Rory – is that many views on Rory’s music from his final decade are often based not on the music itself but rather on his physical appearance at the time.

Knowing what we know now about his struggles with depression also seems to have influenced how his later albums are interpreted. Take Fresh Evidence, for example, which we discuss in Chapter 1.3. While it certainly addresses themes of illness and death, it also explores themes of redemption and forgiveness and includes tributes to Rory’s favourite blues artists, while songs like ‘Alexis’ and ‘The Loop’ are pretty experimental, but these aspects often get overshadowed by the ‘fall’ narrative. Even Jinx from 1982 is now often framed through the lens of Rory’s personal ‘jinx’, as we show in Chapter 1.1.

If someone were to tell me they disliked Defender simply because they didn’t like the music and preferred Rory’s earlier four-piece band, I might disagree, but I would accept their opinion. Ultimately, I would like to see judgements based on the music itself rather than on how Rory looked or his personal struggles during this period.

GS: What do you think it is about Rory’s music that has won him a new following in the years since his death?

LAO: I think there are many factors at play here. The role of Rory’s brother Dónal certainly can’t be overlooked as he has dedicated his life to promoting Rory’s legacy, curating thoughtful releases that align with Rory’s desires and doing everything possible to spread the word about him. It was down to Dónal’s hard work and dedication that Rory’s entire back catalogue was remixed and re-released in Europe in 1998-1999 when Capo Records partnered with BMG. These albums were reissued again in 2010-2011 under Eagle Rock in the US, in 2012-2013 under Sony Music in Europe, and in 2018 under Universal worldwide, which introduced so many new people to Rory’s music. Dónal was also instrumental in making sure many of Rory’s filmed performances, including those at Rockpalast and the Montreux Jazz Festival, were released on DVD in the early 2000s.

Then there’s Rory’s music itself, which possesses a timeless quality. Ironically, the aspects for which he was critiqued during his lifetime – such as his resistance to trends and fashions – have ultimately benefitted him, making his music more relevant today. In fact, for the conclusion of our book, we spoke to a group of young people about what resonates with them in Rory’s music. They said that having grown up in an era dominated by computerised music, they craved analogue music for its breadth, body and richness. They wanted to reconnect with the ‘human’ element in music, and Rory’s authenticity offered just that. Others mentioned feeling scared about the future and searching for hope, which they found in Rory’s music. They identified with many of his own struggles and his ability to produce something beautiful and enduring out of them.

GM: Brothers in rock music tend to have a pretty bad reputation, by and large. What is it about Dónal that made him such a boon to his brother, both during and after his life?

LAO: I always say that Dónal was the perfect yin to Rory’s yang. Outgoing, sociable and always ready to fight Rory’s corner. I think he recognised a certain vulnerability in his brother from an early age and sought to protect him. When the teenage Rory was spat at in the streets for having long hair, for example, Dónal would jump in to defend him, and during the Taste years, Dónal even ran away to Belfast to be by Rory’s side after hearing that he had been beaten up. Dónal possessed a tremendous work ethic and went on to manage all Rory’s business affairs, which allowed his brother to focus solely on performing. This dynamic was crucial to Rory’s success. Dónal also assumed responsibility for much of Rory’s personal life, knowing how challenging it could be for him off the road. For instance, when Rory lived at the Conrad Hotel in his later years, Dónal had meals delivered to his door to ensure he was eating properly.

There’s an interview with Paris Move where Dónal mentions how it was always just the two of them, especially after their parents’ separation, which created a very close bond. He also said that he felt Rory never got the credit he deserved for his music and, as a result, he’s made it his life’s work to rectify that. Although Rory didn’t speak of Dónal often in interviews, when he did, he described him as a “gift from God,” acknowledging that he wouldn’t have persevered without him. Their relationship was truly beautiful.

GS: Rory was a great champion of creativity, imagination and the power of music to mitigate the worst aspects of the human condition. Yet he’s thriving in a medium (digital technology) and on a forum (the internet) that seems intent on problematising, if not entirely erasing, the human propensity to create. Is there a contradiction there?

LAO: That’s a really interesting point, Gerry. We talk in the book about the irony of Rory’s aversion to technology and yet it’s thanks to technology that he thrives today, but this aspect, which you’ve highlighted, adds a layer I hadn’t fully considered. As I mentioned earlier, digital platforms have significantly enhanced accessibility and reach for Rory’s music. However, I also share your concern that they risk diluting the authenticity of artistic expression. I often find myself pondering what Rory would think of today’s technology. Would he embrace social media, for example? There’s an interview from the early 1990s where he remarks on how quickly the world seems to be spinning, so I find it fascinating to speculate how he might navigate our current digital landscape.

In this day and age, I think Rory’s music has to be available on the internet to stay relevant, but we must tread carefully to preserve the essence of his music. In the last year or so, I’ve noticed an increase in AI applications on photos of him, and I sincerely hope that doesn’t extend to his music! Beyond the internet, I’d say that these contradictions between Rory’s values and the modern world are frequently discussed within the fan community. There are debates over whether there should be a biopic, if he should be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, if there are too many releases from the Gallagher estate, even whether his beloved Strat should be put up for auction or not.

From my perspective, I appreciate the creativity that fans can bring to the table online. I see people across social media who are finding new ways to place Rory’s music in a 21st-century context, whether through memes, video montages, artwork, poetry, stories, videos of themselves interpreting his songs… I love the grassroots nature of the Rory fan community; we’re a fairly small but fiercely loyal group who often collaborate together on Rory projects, Rewriting Rory being a key example.

In the book, we include a lovely quote from Dave Fanning that I think gets to the heart of the matter: our love for music should ultimately be based on our personal connections to it, both now and in the future.

GS: What can we identify in Irish cultural history as influential on Rory’s embrace of the blues?

LAO: This is an interesting question as I conducted a study a few years ago on expressions of Irishness in the comments section of the Rory Gallagher YouTube channel. One of the recurring themes was the question of what made an Irishman like Rory excel at playing the blues. Quite often, people argued that this connection stemmed from Ireland’s long history of oppression by the British and the ensuing political turmoil. They saw the blues and Irishness as intertwined and intimately connected. This theme also comes up in press articles – unsurprisingly those outside the Anglo media – who emphasise the idea of the Irish as oppressed people. I remember one French journalist writing, “Get colonised for 700 years and see how you feel!” However, it’s worth noting that Rory himself addressed this topic in a 1976 interview and said that he didn’t consider himself an oppressed person per se; rather, he viewed the blues as a means of expressing deep emotions and sadness within him.

From a cultural perspective, Rory’s access to the blues can be traced back to his time in Derry as a young boy, where he listened to broadcasts from the American Forces Network (AFN) radio. The presence of a US Naval Base in Derry since the 1940s allowed for a unique cultural exchange as AFN provided access to a variety of music that was not readily available in Ireland at the time. This exposure played a crucial role in shaping Rory’s musical tastes. In addition to AFN, Rory’s Uncle Jimmy, who had emigrated to North America, returned to Cork in the 1950s with numerous blues, country and folk records that profoundly influenced Rory’s musical development.

Musically, I think Rory’s work showcases a distinctly Irish influence that is often overlooked. His unique approach to playing the blues reflects a Celtic sensibility, shaped by his upbringing and exposure to traditional Irish music. We give some examples of this in Chapter 4.6, such as how he blended triplets from traditional jigs and reels with 12-bar blues licks, used DADGAD tuning and frequently combined major thirds with flat sevens. His note-bending is also reminiscent of the sound of uillean pipes or vocal wailing, while his slide playing, often executed with his little finger, can be traced back to his familiarity with the mandolin.

GS: Counter-factualism can be great fun: what would have happened, do you think, if Rory had joined the Rolling Stones?

LAO: What immediately comes to mind is Bob Geldof’s statement in the Ghost Blues documentary: that Rory “could never have put up with the bollocks of Mick or Keith” [laughs]. He goes on to say that Rory was too much of his own man – a lead player, singer and songwriter – making it hard to envision how it would have worked. I’m inclined to agree with him. Rory was notoriously independent, particularly after his experiences with Taste, which made him value his autonomy and control over his music. I think Rory’s avoidance of the whole rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle would have also made it hard for him to fit in. The Stones were banned from several countries at the time due to their substance abuse too, which would have been a problem.

However, it’s interesting to consider Rory making a guest appearance on one of their albums or concerts – he often expressed his openness to that kind of thing with other artists, seeing it as a “holiday” for him. Rory also held Keith Richards in high regard, often citing him as one of his favourite rhythm guitarists, so it would have been intriguing to see them play together. Dónal claims that Rory helped inspire the riff for ‘Hot Stuff’ – it certainly has a ‘Jackknife Beat’ vibe to it. If this is true, then it offers a glimpse into the potential for a unique fusion of their musical styles.

GS: And finally: given the extent to which ‘meaning’ in music is a function of the artist’s persona as well as the medium itself, to me it doesn’t seem to make much sense to try to dissociate them. In that regard, it’s instructive to note that the egregious sexual behaviour of many (male) rock stars from the 1960s to the 1990s doesn’t bear much scrutiny by today’s standards. Was Rory’s avoidance of that behaviour a conscious decision on his part, or was it driven by other issues?

LAO: There’s long been speculation over Rory’s avoidance of such behaviour and what might have motivated it. I don’t think there’s one definitive answer, but I’d say it was a combination of his unwavering dedication to music, his upbringing and his personal values. As his brother Dónal has often said, Rory treated music like a “vocation in the priesthood” and he devoted himself entirely to it from a young age, meaning that there was room for nothing else in his life. He was deeply serious about his craft and saw himself first and foremost as a “musician”, not a “rockstar” or any other label, so I think his passion for music and commitment to its integrity were always at the forefront of his mind.

You also have to remember that Rory grew up in a deeply conservative Ireland, shaped by traditional values. He was a devout Catholic who attended Mass regularly throughout his life, often even while on tour, and was known for his strong morals and gentlemanly behaviour. You know, he never swore, stood up when a woman walked into the room, called his mother every night before he went to bed and even changed the lyrics in blues covers if they were sexist or racy. I think his personality traits – his shyness, introverted nature and preference for his own company – also may have distanced him from the excesses typically associated with rock stardom and set him apart from many of his contemporaries. In fact, I’d say that Rory’s fundamental sense of human decency is a key reason why he continues to resonate with so many people today.

Rory Gallagher: The Later Years out now!

Biographies

MJ Steel Collins is a poet, publisher, music fan and Rory Gallagher nerd hailing from Scotland. The Rory fondness seems somewhat fated as MJ’s great granny was also born in Ballyshannon like Rory, only some four decades or so earlier. When not listening to music (Rory, of course), MJ can be found surgically attached to a Kindle hoovering Urban Fantasy novels, Tom Slemen’s Haunted Liverpool and history books. She runs a small publishing press and is attempting to put together a poetry volume. She has also written about the paranormal and music journalism. Occasionally, she might pick up a guitar. Her previous one near enough melted when trying to learn ‘Shadow Play’ and was subsequently replaced.

Gerry Smyth is Professor of Irish Cultural History at Liverpool John Moores University. His published research on Irish music includes Noisy Island: A Short History of Irish Popular Music (2005), Music in Irish Cultural History (2009), Celtic Tiger Blues: Music and Modern Irish Identity (2016) and, most recently, Joyces Noyces: Music and Song in the Life and Literature of James Joyce (2021). Gerry is also a musician and composer, and has released a number of albums of progressive folk music (mostly maritime in derivation) with various friends and guests.

Leave a reply to Jacques ”Jeck” MOUCHET Cancel reply