Rory Gallagher

“Success, failure, honour or oblivion. None of that means anything to me.”

Irish Tour ’74 is a live album that is liked even by people who typically dislike these types of recordings. In 2024, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of its original release, another gigantic version will be released, which is the perfect excuse to remember that incredible moment in the history of rock music and its creator – the great and never praised enough, Rory Gallagher. In the words of Paul McGuinness, manager of U2, “The first Irish rockstar and an example to follow.”

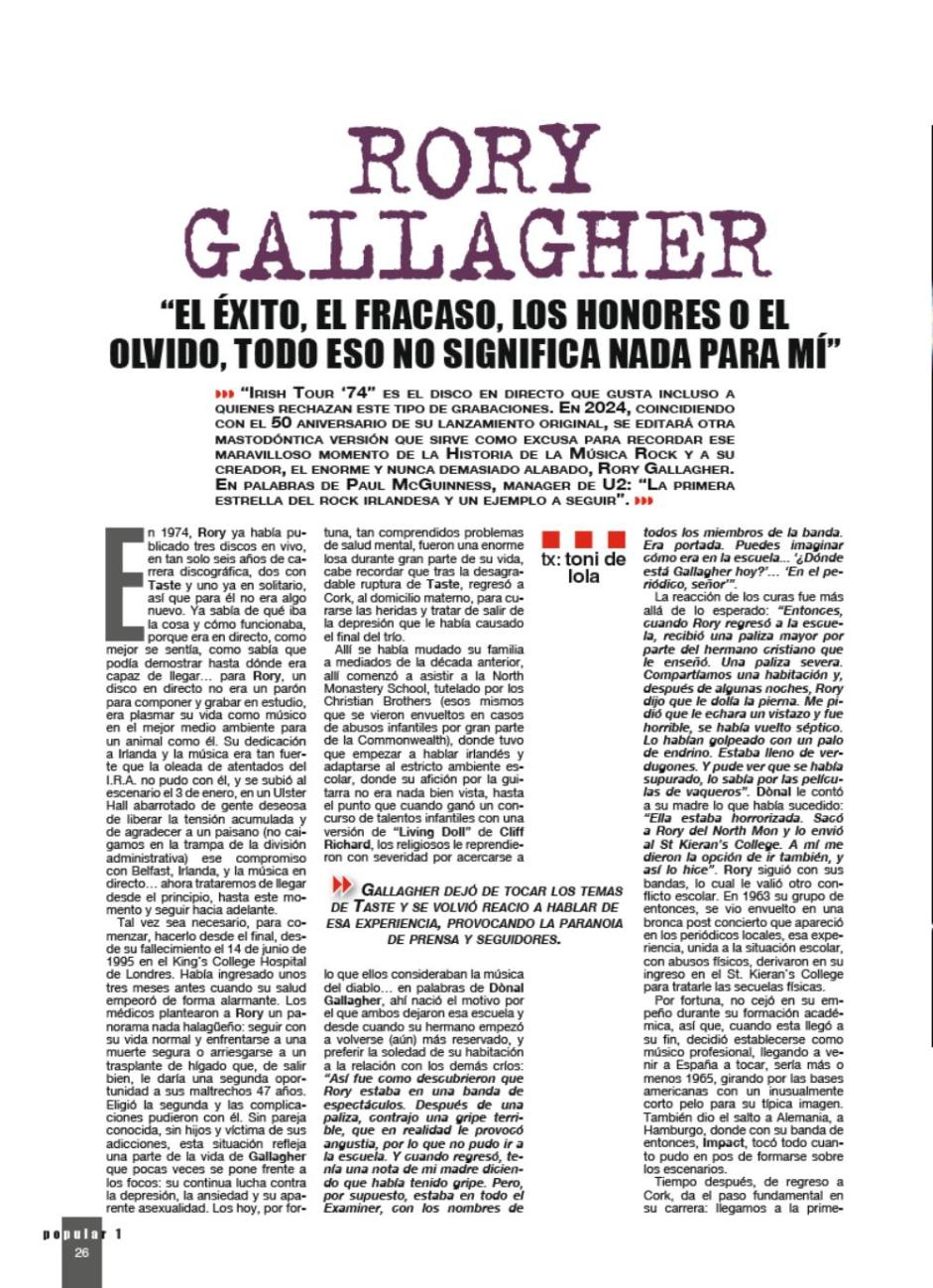

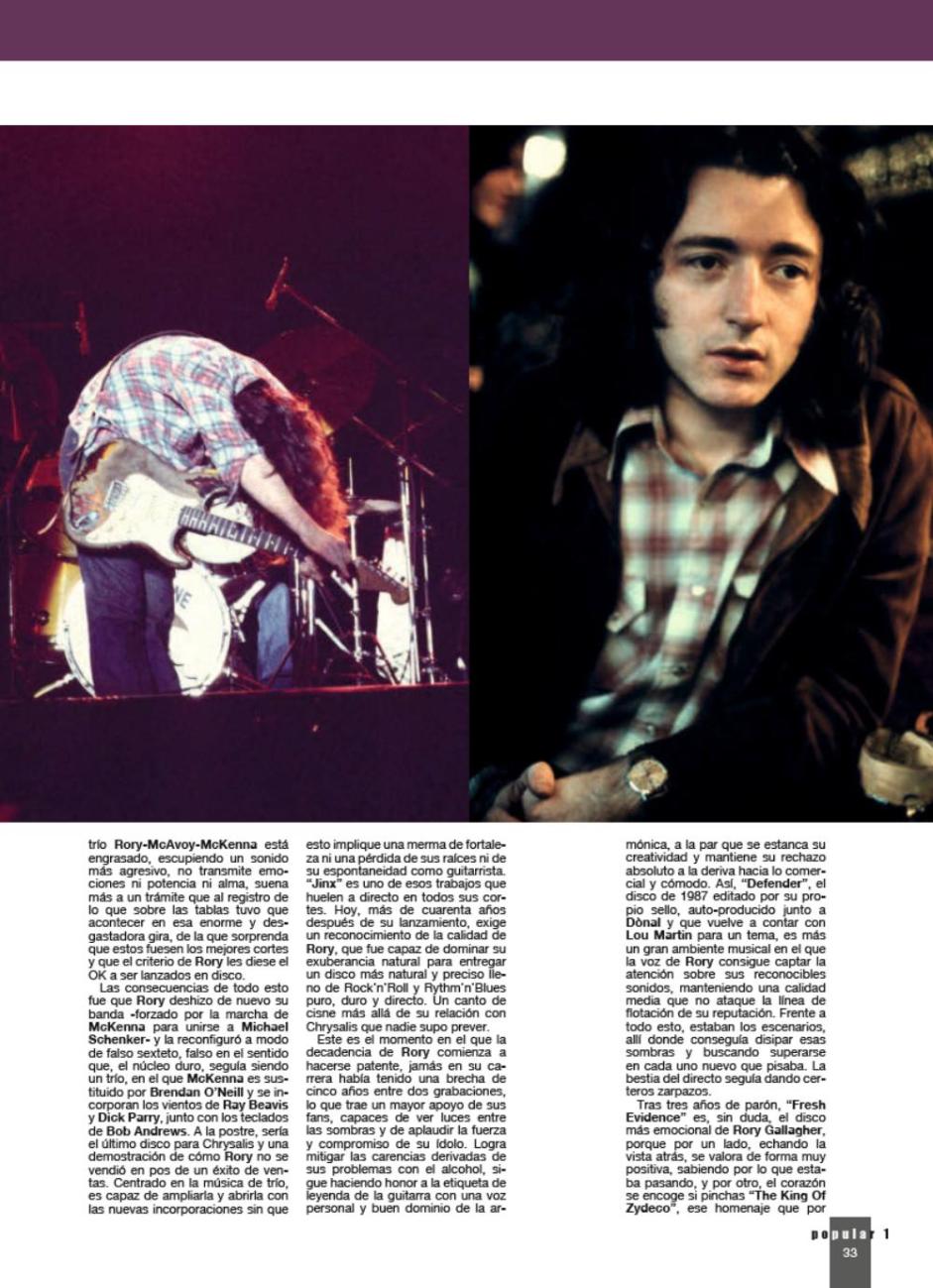

In 1974, Rory had already released three live albums in just six years of his recording history: two with Taste and one as a solo artist, so it was nothing new for him. He already knew what it was like and how it worked because it was live that he felt most comfortable, where he knew he could demonstrate his full capabilities… for Rory, a live album wasn’t a stopgap to make time to compose and record in the studio; it was a chance to display his life as a musician in the best environment for an animal like him. His dedication to Ireland and music was so strong that the wave of IRA terrorist attacks couldn’t stop him and he went on stage on 3 January [sic] in an Ulster Hall packed with people anxious to be liberated from the pent-up tension and to appreciate a fellow countryman (let’s not fall into the trap of administrative divisions) for his commitment to Belfast, Ireland and live music… now we will try to start from the beginning to reach that moment and then go further on.

Perhaps it’s necessary to start from the end, from his death on 14 June 1995 at King’s College Hospital in London. He had been admitted three months earlier when his health alarmingly worsened. The doctors presented Rory with a rather unpleasant panorama: continue his normal life and face a certain death or risk a liver transplant which, if it went well, would give him a second chance at his damaged 47 years of age. He chose the second option and complications brought his end. No known partner, no children and victim of his addictions, this situation reflects a part of Gallagher’s life that is only seldom brought into focus: his continual struggle with depression, anxiety and his apparent asexuality. These mental health problems that are, fortunately, better understood today were a humongous millstone throughout most of his life. One only has to remember that after the regrettable break-up of Taste, he returned to Cork to his mother’s house to lick his wounds and try to come out of the depression caused by the end of the trio.

His family had moved there at the end of the previous decade and it was there that he started to attend North Monastery School, run by the Christian Brothers (the very same people who have been involved in cases of child abuse all over the Commonwealth), where he had to start speaking Irish and adapt to a strict school environment, where his love for guitar was not viewed well, to the point that when he won a children’s talent contest with a version of ‘Living Doll’ by Cliff Richard, the priests reprimanded him severely for playing what they considered to be the devil’s music… according to Dónal Gallagher, this was why they both left the school and this was when his brother started to become (even) more reserved and preferred the solitude of his bedroom than interacting with other children: “That was how they discovered that Rory was in a showband. After taking a beating, he caught a terrible flu, which was actually anxiety, and couldn’t face going back into school. And when he returned, he had a note from my mother saying that he had had flu. But, of course, it was in The Examiner with the names of all the band members. It was on the front cover. You can imagine what it was like at school… “Where is Gallagher today?”… “In the paper, sir.”

The priests’ reaction was even worse than expected: “So, when Rory returned to school, he received an even bigger beating from the Christian brother who taught him. A severe beating. We shared a bedroom and, after a few nights, Rory said that his leg hurt. He asked me to take a look and it was horrible. It had become septic. They had hit him with a blackthorn rod. It was full of welts. And I could see that it was infected. I knew from the cowboy movies.” Dónal told his mother what had happened: “She was horrified. She took Rory out of North Mon and sent him to St Kieran’s College instead. They gave me the option of going too, so I did.” Rory continued with his bands, which led to another school conflict. In 1963, his group at the time were involved in a post-concert brawl that appeared in the local papers. That experience, along with the situation at school, the physical abuse, led to his admission at St Kieran’s College to try and heal the physical consequences.

Luckily, throughout his schooling, he didn’t give up on his goal, so when he got his leaving certificate, he decided to establish himself as a professional musician, going on to play in Spain around 1965 and touring the American bases with an unusually short haircut for his typical image. He also hopped over to Germany, to Hamburg, where with his band of the time, Impact, he played all he could in order to learn his trade on the stage.

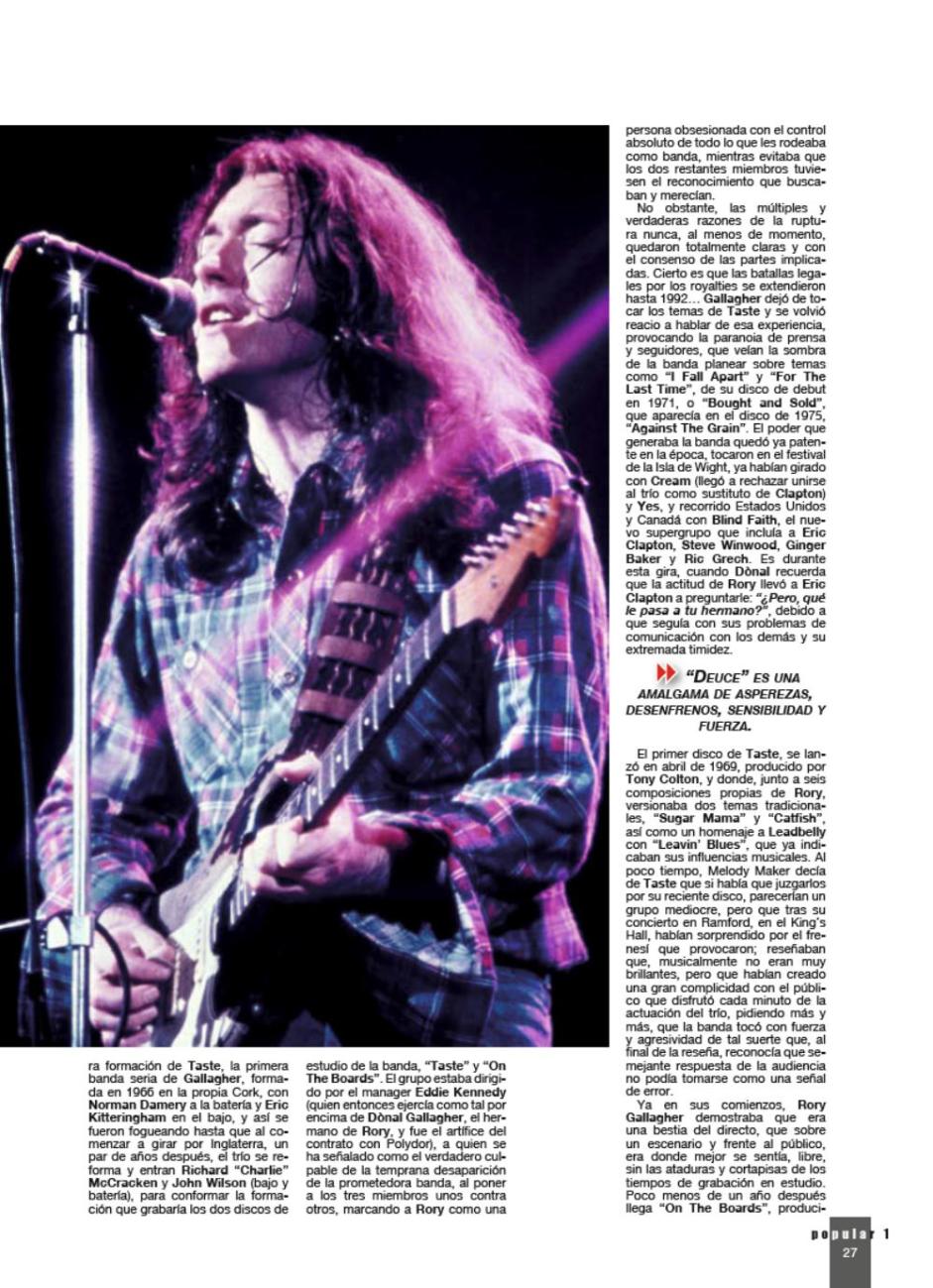

A while later, when returning to Cork, he took the fundamental step in his career: the first formation of Taste, Gallagher’s first serious band, formed in 1966 in Cork city, with Norman Damery on drums and Eric Kitteringham on bass. And there they slogged until, when starting an English tour a few years later, the trio reformed and in came Richard ‘Charlie’ McCracken and John Wilson (bass and drums) to form the trio that would record two studio discs: Taste and On the Boards. The group were managed by Eddie Kennedy (who then served above Dónal Gallagher, Rory’s brother, and was the architect of the contract with Polydor) who was the person truly responsible for the swift end of the promising band by pitting the three members against each other, framing Rory as a person obsessed with having absolute control over everything concerning the band, while not allowing the other two members to have the recognition that they craved and deserved.

However, the multiple and real reasons for the break-up have never, at least for the moment, been completely clear and agreed by all those involved. One thing is for sure – the legal battles for royalties went on until 1992… Gallagher stopped playing Taste songs and became reluctant to talk about the experience, causing the press and fans alike to see the shadow of the band clearly in songs like ‘I Fall Apart’ and ‘For the Last Time’ on his 1971 debut album or ‘Bought and Sold’ which appeared on his 1975 album Against the Grain. The power of the band was already evident at the time; they played the Isle of Wight Festival, had already toured with Cream (Rory refused to join the trio as a replacement for Clapton) and Yes, and toured the United States and Canada with Blind Faith, the new supergroup that included Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker and Ric Grech. It was during this tour that Dónal remembers that Rory’s attitude led Eric Clapton to ask him, “What’s wrong with your brother?” due to the fact that Rory had problems communicating with the others and was extremely shy.

The first Taste album was released in April 1969 and produced by Tony Colton. Together with six compositions by Rory, it saw covers of two traditional songs, ‘Sugar Mama’ and ‘Catfish’, as well as a homage to Leadbelly with ‘Leavin’ Blues’ which already indicated Rory’s musical influences. In a short time, Melody Maker said that if Taste were to be judged on their recent album, they would seem a mediocre group, but after their concert in Ramford, in the King’s Hall, they were surprised by the frenzy they generated; they argued that Taste were not musically brilliant, but they had created a huge rapport with the audience who enjoyed every minute of the trio’s performance, asking for more and more, and that the band played with force and aggressivity in such a way that, by the end of the review, they admitted that the similar response from the audience couldn’t be mistaken.

Already at the beginning, Rory Gallagher showed that he was a beast when playing live, and it was on stage and in front of an audience where he felt best, the most liberated, without the ties and limitations of recording time in the studio. A little less than a year later, On the Boards came out, produced again by Colton. This time, there were no longer covers or homages, and the ten songs came from the genius of Rory. It reached number 18 in the charts in the UK. It had great critical success to such a point that the legendary Lester Bangs said of them in Rolling Stone, “Taste is evolving into much more than just another heavy voltmeter trio (…) Gallagher has digested his mentors, be they blues bards, jazzmen or the Rolling Stones. He is his own man all the way. It may seem unfair to concentrate almost exclusively on Gallagher, but the group is really his own vehicle in every way (…) The compositions are all excellent (…) Taste have arrived.”

Well, Taste came, saw, conquered… and disbanded at the end of the same year; their last concert was on New Year’s Eve 1970 in Belfast. Posthumously, two live albums from that era were released: Live Taste from 31 August 1970 in Montreux with ‘Sugar Mama’ and ‘Catfish’ that were already familiar from their first album, two covers, ‘Gamblin’ Blues’ by Lil’ Jackson and the powerful ‘I Feel So Good’ by Big Bill Broonzy, topped off by ‘Same Old Story’, Rory’s composition, also from the homonymous debut. The second live album was recorded during their earthshattering concert at the Isle of Wight, an example of the absolute power of the trio and above all of Rory Gallagher live.

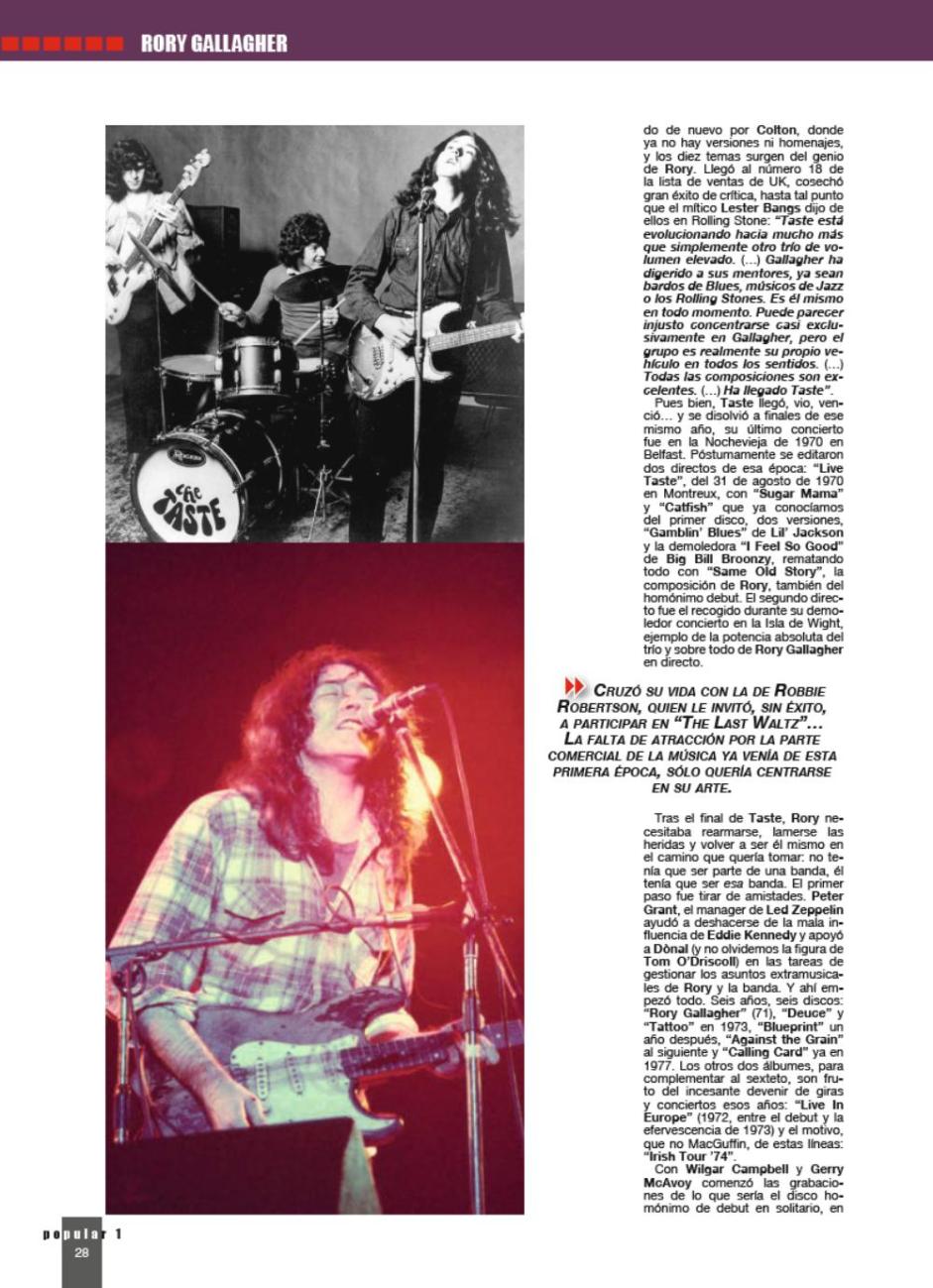

After the break-up of Taste, Rory needed to take stock, lick his wounds and go back to being the one in control of which path to take: he didn’t have to be part of a band, he had to be that band. The first step was to make use of friendships. Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin’s manager, helped to get rid of the bad influence of Eddie Kennedy and supported Dónal (and let’s not forget, Tom O’Driscoll) in the task of managing the extramusical responsibilities of Rory and the band. And everything started from there. Six years, six albums: Rory Gallagher (71), Deuce and Tattoo (in 73), Blueprint a year later, Against the Grain the year after and Calling Card in 1977 [sic]. The other two albums, to complete the sextet, are fruit of the incessant array of tours and concerts those years: Live in Europe (1972 between the debut and the effervescence of 1973) and the non-MacGuffin motive of this article: Irish Tour ’74.

With Wilgar Campbell and Gerry McAvoy, Rory started the recording of what would be his homonymous debut solo album in Advision Studios. To totally break the emotional burden with Taste, he started to produce the albums himself, supported by Eddy Offord as sound engineer, and with whom he had worked on the last Taste album – a fact that demonstrates Rory’s ability to overcome his emotions. For a first album, it appears both varied and solid, grounded in an exceptional stylistic cohesion which, with the passing of time, would go on to be influential in the career of artists as different as Joe Bonamassa and Slash. Even the most predictable song ‘It Takes Time’ has its point, although, let’s face it, it pales next to the jazzy power of ‘Can’t Believe It’s True’ or the delicateness of the trio in ‘I’m Not Surprised’, ‘For the Last Time’ and ‘Just the Smile’ or the fury of ‘Hands Up’, ‘Sinner Boy’ and the magical ‘Laundromat’, which accompanied Rory immutably throughout the first years of his career as a solo artist. The whole album shows a Rory far from the spectacular solos, almost as if he was taming an inner beast that is struggling to come out and which he knows is still not the right moment to let it run amok.

Half a year later, Deuce arrived – an amalgamation of roughness, wildness, sensitivity and force. It features songs that could be considered rehearsals for the future, such as ‘I’m Not Awake Yet’ or ‘Don’t Know Where I’m Going’. And then there is ‘Crest of a Wave’, the absolute closer, a song that almost seems like it’s going to explode, but doesn’t need that artifice to rise almost by itself. An album that still today goes somewhat unnoticed by most fans, but which contains gems like ‘Used to Be’ or ‘There’s a Light’. Here, we do see Rory demonstrating how he has to play a guitar solo that not only puts the focus on the guitarist, but also serves as a binding element of the song. It’s an album that gathers the previous era of Gallagher, compresses it, expresses it and starts to distil it for what was to come in the following years.

1972 opened with the incandescent Live in Europe. Rory opted to air some of his new compositions directly on stage, leaving space only for ‘Laundromat’ and ‘In Your Town’ as songs from the earlier albums. The general opinion was that it was the first of his great albums, outshining those released by him until then. He pays homage to Junior Wells (‘Messin’ with the Kid’), Blind Boy Fuller (‘Pistol Slapper Blues’) together with the traditional ‘Bullfrog Blues’, while he introduced ‘I Could’ve Had Religion’, which starts off with a delicate harmonica before a slide enters that makes the audience fall silent with just one instrument, leaving them in that state until the band enters subtly, slowly, even delicately… The other new song is ‘Going to My Hometown’ and here everything topples down, the audience explodes along with the band and all that’s left is to let yourself be crushed by those three guys on stage.

Blueprint appeared in 1973 with two significant changes. On the one hand, the replacement of Campbell on drums with Rod De’Ath and the inclusion of Lou Martin as keyboardist. Just like that, that magic blues trio formation disappeared to give way to a big four that would open Gallagher’s music to a more creative universe that he had as an artist. ‘Daughter of the Everglades’ serves as an example, where the fusion of Martin and Gallagher is a great example of how two musicians can gel in such a short amount of time together. With the passing of time, this album seems more like a practice run, more like a piece with great moments, some almost unbeatable like ‘Seventh Son of a Seventh Son’, surrounded by other songs in which Rory seems to be rehearsing the possibilities of the new formation on the basis of the blast of most standardised blues rock, passed through the Gallagher sieve. But they’re not to be seen as fillers, but rather learning, experiments, tests… More than an excess of creativity, Gallagher is urged to create something big, something imperishable that could be played live over and over again without wear and tear, without a sensation of weariness. Tattoo was the work that stood on tiptoes and stretched its arm to reach the moon… and Rory almost managed it.

They returned to rehearse for the first time in Ireland. Rory was happy to return to his beloved Cork. He couldn’t even go out on the street, so Dónal hired a boat club on the river, where they could rehearse and eat home-cooked food without the continuous interference of fans. The quartet was now established, the pieces fit, above all Lou Martin who was that element that gave some extra quality to Rory’s compositions, who absolutely opened them up every time that Rory wrote a line. They returned to London and there Gallagher was back to himself, full of introspection (or rather, all that his shy demeanour allowed him to dive into himself); there is bitterness, forcefulness (is there anyone capable of finding triviality in the album’s lyrics?), melancholy and a sincerity that can even lead the listener to reflect.

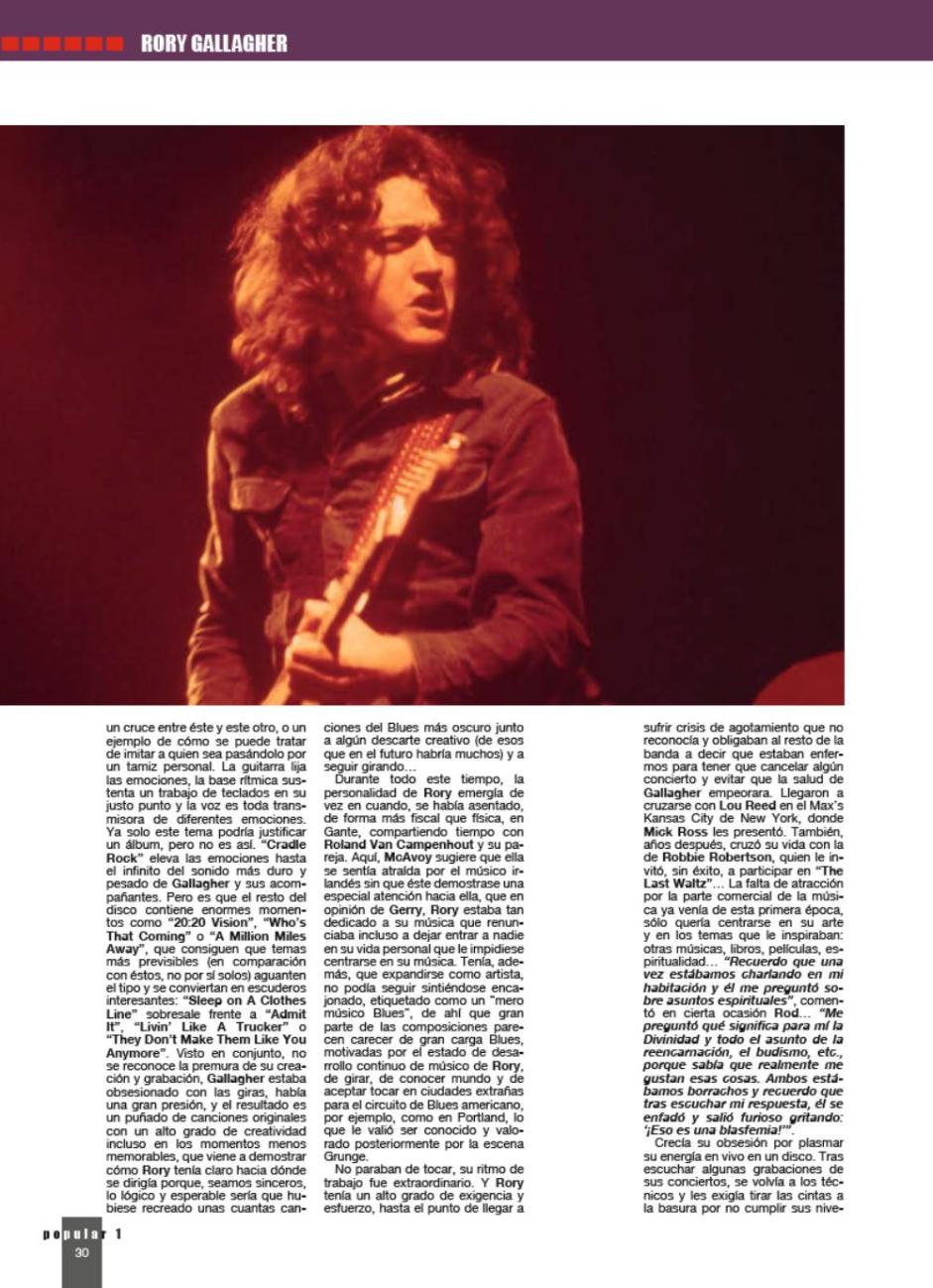

Its opener ‘Tattoo’d Lady’ is already a declaration of musical intent that goes further than those critics who claimed that the song was a cross between this and that, or an example of how Rory tried to imitate whoever and just passed it through his personal sieve. The guitar sands the emotions, the rhythm section sustains the keyboards perfectly and Rory’s voice is transmitted with a range of emotions. This song alone could justify an album, but it’s not like that. ‘Cradle Rock’ elevates the emotions to the infinitely hardest and heaviest sound of Gallagher and his accompanists. But the rest of the album also contains incredible moments like ‘20:20 Vision’, ‘Who’s That Coming’ and ‘A Million Miles Away’, that make more predictable songs (in comparison with the others, not by themselves) hold up and become interesting squires: ‘Sleep on a Clothes Line’ stands out compared to ‘Admit It’, ‘Livin’ Like a Trucker’ and ‘They Don’t Make Them Like You Anymore’. Viewed together, it’s hard to recognise the haste of its creation and recording. Gallagher was obsessed with touring, he put huge pressure on himself, and the result is a fistful of original songs with a high level of creativity, even at less memorable moments, which come to demonstrate that Rory was clear where he was heading because, let’s be honest, the logical and expected thing would have been to have recorded a few of the most obscure blues songs along with some creative discards (there would be a lot in the future) and to keep touring…

During all this time, Rory’s personality emerged now and again. He had settled – more fiscally than physically – in Ghent, sharing a house with Roland Van Campenhout and his girlfriend. McAvoy suggests that Van Campenhout’s girlfriend was attracted to the Irish musician, but that he didn’t show her any particular attention. In Gerry’s opinion, Rory was so dedicated to his music that he refused to let anyone into his personal life that would impede him from concentrating on his music. He, above all, wanted to expand as an artist. He couldn’t keep feeling boxed in, tagged as a “mere blues musician”, hence the majority of his compositions seem to lack a huge blues load, motivated by the continual development of Rory’s music, of touring, of getting to know the world, and accepting playing in strange cities on the American blues circuit, for example, like in Portland, which led to him later being known and valued by the grunge scene.

They didn’t stop playing. His work rate was extraordinary. And Rory had such a high level of demand and effort to the point of suffering exhaustion, which he refused to recognise. So much so that the rest of the band were obliged to tell him that they were sick to get him to cancel some concerts and stop his health from getting worse. They managed to cross paths with Lou Reed in Max’s Kansas City in New York, where Mick Ross introduced them. Also, years later, he would cross paths with Robbie Robertson, who invited him unsuccessfully to participate in The Last Waltz… Rory’s lack of interest in the commercialisation of music was already apparent at this time. He just wanted to focus on his art and the themes that inspired him: other musicians, books, films, spirituality… “I remember that once we were chatting in my room and he asked me about spiritual matters,” Rod said on one occasion, “He asked me what spirituality meant to me and about reincarnation, Buddhism etc. because he knew that I really liked that stuff. Both of us were drunk and I remember after hearing my response, he got really upset and left the room shouting, “That’s blasphemy!”

His obsession to capture his live energy on an album grew. After listening to various recordings of his concerts, he went back to the technicians and asked them to throw the tapes in the bin as they didn’t meet his high level of expectation. If it were up to him, he would only record live. Or not even that; he would only play live. “He was a live musician,” said Lou Martin, “He didn’t like the studio because he would play against the walls and he didn’t sense the feeling of the audience. But he had to record albums for the record company that contracted him.” So, Irish Tour ‘74 came along, but let’s skip that moment for now and continue with Rory’s pathway.

We are now in 1975: change of record company. Chrysalis comes into play – in an eagerness to be able to maintain a greater level of control over his music – and the last albums of the effervescent decade of the 70s arrive… as well as the call of the Stones to come and join them. Heathrow Airport, 23 January 1975: Rory Gallagher arrives to catch a flight to Rotterdam as a consequence of the ill-timed phone call a few days before that Ian Stewart had made to his mother’s house, which put the whole family on alert when they heard the famous phrase, “My name is Ian Stewart. I’m looking for Rory Gallagher.” The first thing they thought was that the IRA had turned their attention to Rory… but no, the Rolling Stones’ keyboardist was following out the instructions of Jagger and Richards to try Rory as a replacement after the sudden departure of Mick Taylor. The band had sounded out Jeff Beck, Steve Marriott, Chris Spedding… and they kept trying to find the exact piece when they knocked on Gallagher’s door, a lover – like them – of old bluesmen like Leadbelly and Albert King. Let’s remember that Gallagher always said of himself, “I never thought of becoming a loyal interpreter of the old blues, not even a modern young bluesman. I wanted to be myself in music, yes, a fan of the blues and with a bit of Eddie Cochran and Buddy Holly.” Dónal Gallagher remembers that moment when the telephone rang at the family home at one o’clock in the morning and he had to go and wake up his brother who thought that Dónal was playing a trick on him. But he took the telephone, listened and surprisingly agreed to go to Rotterdam to see the band.

Once there, Mick was waiting when he saw a guy with a suitcase, an amplifier and a rigid guitar case containing his beloved ’61 Stratocaster. Taxi to the De Doelen hall and there started three days of work, mutual knowledge and lots of improvisation. Despite the absence of Keith for the first time, Rory wasn’t bothered, as playing with Charlie Watts was going to be a great experience for him. He had commented on multiple occasions to Gerry McAvoy that Watts was for him a drummer who knew how to dominate rhythm, get the songs and drive them perfectly.

Mick taught Rory a song, then he left him alone and the Irishman started with a riff that swiftly sent Jagger back to reality: there before him he had someone clearly capable of improvising a riff by just hearing a small segment of a song. That was ‘Hot Stuff’, and on the album it was played by Harvey Mandel, one of the “fathers” of tapping and another of the names bounced around to join the band permanently… despite everything, Rory didn’t manage to make an impression on the band, above all because of Keith’s passivity. Rory even took the trouble of going to the Stones hotel and trying to see him to clarify the situation. Gallagher was about to start his Japanese tour and he didn’t have any interest in going to Tokyo without knowing what options he had with the band. He went to Mick and said, “Please let me know what’s happening because tomorrow I have to catch a flight to Tokyo.” Mick (who, according to all the papers, practically wasn’t speaking to Keith at this point) told him to go up to Richards’ suite, but the human riff wasn’t in a state to have a proper conversation with anyone all night, so Rory decided to collect his luggage and return to continue with his tour of Japan.

Now it’s time to wonder what Black and Blue would have been like if Rory had joined them, if it had gone down like that, if his presence could have gone from testimonial to staying in the background and if Rory would have felt comfortable with that. If Keith’s attitude was no more than an excuse for a decision that was already taken, because Rotterdam brought back to Rory the memory of those times in Taste and he didn’t want to return to that situation, even if it was within a huge band like the Rolling Stones. In the following years, Rory Gallagher recorded four albums before the end of the decade: Against the Grain, Calling Card, Photo Finish and Top Priority. If the new record label was a place where he received closer treatment and greater freedom, the title of the first release for them was already a declaration of intent.

The rebellion of Cochran, Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis flourishes on one album – Against the Grain – which shows a more furious Rory, more concentrated than ever with the possibilities of his guitar, leaving space for McAvoy and De’Ath so that Lou Martin can launch all his weapons. The quartet is oiled in an efficient way and they deliver a tremendously varied album that is not far from the blues, whether electric or acoustic with ‘Out on the Western Plain’ and ‘All Around Man’, covers of Leadbelly and Bo Carter; moments with epic touches like ‘Lost at Sea’, a powerful blast like ‘Let Me In’. And this, almost on top of all, ‘Bought and Sold’, Rory’s unifier of the moment, which started to open the great doors of the US, a radio friendly, danceable and plausible song to add value to the whole album.

The second release with Chrysalis, Calling Card, was born already with some congenital wounds. Roger Glover would act as co-producer and his puritanism, his devotion to clean and crystalline sounds, clashed with Rory’s concept of recording as if he were live. In addition, Gallagher did not like the original mixes by Eliot Mazer. In fact, he was furious when Chris Wright asked for the 5 and a half minutes of ‘Edged in Blue’ to be cut to be able to release it as a single that would give its name to the album. Nonetheless, Calling Card shows Rory Gallagher’s creativity with more faces than ever, a sort of calling card in which he wants to show where he can move, insisting that he is more than just a blues musician, that he is Rory Gallagher… He had to keep looking for that way of being him, getting far away from labels and corsets. A case in point is ‘Barley and Grape Rag’, a delicious rarity that will turn many people into Gallagher fans who perhaps never imagined it. It is one of those songs that can stand in the shade of Rory’s discography until you give it the opportunity to shine away from its comparisons.

Two years after, this magic would have other protagonists. De’Ath and Martin left Rory (or rather, he dispensed with them) and he returned to the power trio formation with Ted McKenna on drums, who had played with Alex Harvey. Rory had seen the Sex Pistols on 14 January 1978 at the Winterland Ballroom, which perhaps was a jolt for his creativity. Photo Finish is an intriguing album in the sense that it is the child of speed (the title is not a coincidence, given that most of it comes from discards from Calling Card that Gallagher didn’t approve of), but it contains songs worthy of slowing down to stop and appreciate them in peace like ‘Mississippi Sheiks’, together with direct blows to the face that seem to feel the influence of the speed and crudeness of punk. ‘Shin Kicker’ is an example of that primal Rory, full of grease and willingness to take on the world. Gerry McAvoy plays as always and at the same time more rampantly, and McKenna’s style is perhaps what Gallagher had been looking for since sharing notes with Watts (give or take some obvious differences, of course). An album that has so much more than the ever-repeated ‘Shadow Play’…

The 70s are about to end, the group is about to tour the United States, and Chrysalis, that record label that Rory thought were going to look after him, pushed to take advantage of the the relative fame achieved and the band’s good form. The artist/record company divergences are reflected in the title: for the record company, it was a necessity to not let business opportunities pass by, while for Gallagher, it was to remember that he had to be a top priority for Chrysalis, he needed to feel supported in every artistic step that he decided to take. The result is a work in which the influence of blues or blues rock is more diluted than ever up until this point, despite it being the base of all on which Top Priority was constructed. It is much more than the album of ultra fans, a work grounded in the time in which it was released, modern in the positive sense of the term. If ‘Bad Penny’ is the hit that everyone knows,’ Public Enemy No. 1’ is an example of impedance and ‘Philby’ shows that Gallagher was a cultured man: “I love all that spy stuff. I thought that there were some parallels with the world of rock. It is a spy song and he (Kim Philby is the double agent on which John le Carré based Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) is the definitive spy. I added the electric sitar to give it a lightly exotic feeling and also it has a bit of mandolin. I hope to make more songs like that one, using more unusual topics.” Rory Gallagher in a pure state, right?

The 1980s began with a live album, Stage Struck, the result of the 1979 tour and a good part of 1980 promoting Top Priority. If Rory’s true force was always live, the recording of that tour pales when it comes to capturing that force and fury. An excessively clean production and a selection of debatable cuts make that album a step back in Rory’s achievement of making the perfect live album. Nothing stands out, nothing calls the attention, and although the Rory-McAvoy-Mckenna trio is heavy, spitting out a more aggressive sound, it doesn’t transmit emotions nor power nor soul. It sounds more like a procedure than a record of what happened on stage on that enormous and exhausting tour. It is surprising that these were the best cuts and that Rory – ever the perfectionist – gave it the OK to be released as an album.

The consequences of all this were that Rory once again broke up the band – forced by the exit of McKenna to join Michael Schenker – and he reconfigured it in the way of a false sextet. False in the sense that the hard nucleus continued being a trio in which McKenna was replaced by Brendan O’Neill and incorporated Ray Beavis and Dick Parry on brass together with the keyboards of Bob Andrews. It would be the last disc for Chrysalis and a demonstration of how Rory never sold himself in the pursuit of successful sales. Centred on the music of the trio, he is capable of amplifying it and opening it with new incorporations without this implying a lack of strength nor a loss of his roots or his spontaneity as a guitarist. Jinx is one of those works that seems live in all its cuts. Today, more than 40 years after its release, it demands a recognition of Rory’s quality, who was capable of dominating his natural exuberance to deliver a more natural and precise album full of pure, hard and direct rock & roll and rhythm & blues. A swansong further from his relationship with Chrysalis that nobody could predict.

This is the moment where Rory’s decline [RR: WTF!] starts to become apparent. Never in his career had he had a break of five years between two recordings, which brings greater support from his fans, capable of seeing light amongst the shade and applauding their idol’s effort and commitment. He manages to mitigate the deficiencies stemming from his alcohol problems [RR: again, WTF!] and continues to honour the tag of guitar legend with his personal voice and clear mastery of the harmonica, but at the same time his creativity is stagnating [RR: Bullshit!] and he maintains an absolute rejection of a drift towards the commercial and comfortable. So, Defender, the 1987 disc released by his own label, self-produced together with Dónal and which saw Lou Martin return for one song, is more of a great musical environment in which Rory’s voice manages to draw attention to his recognisable sounds, maintaining an average quality that doesn’t attack the waterline of his reputation. Together with all this were scenarios where he managed to dissipate those shadows and sought to improve himself in each new one he stepped on. The beast of the live shows continued delivering accurate blows.

After three years of hiatus [RR: Not true!], Fresh Evidence is, without doubt, the most emotional Rory Gallagher album, because on the one hand, looking back, it is valued very positively knowing what was going on for him, and on the other, your heart sinks if you listen to ‘The King of Zydeco’ – a homage that, despite the amount of love put into it, is clearly not at the top of even the average of his compositions [RR: totally disagree!]. Perhaps the seriousness and darkness of the songs have created that feeling with the passing of time, of a farewell disc where Rory wondered if he would return and record anything else. Perhaps that is why he spent six months in the studio until he came up with the final version of each song. “That was really hard for us, I can assure you. We took around six months to do it, which is quite a lot of time. It sounds like relatively simple music, but we were trying to create a good vintage and ethnic sound for it.”

To honour the memory of Rory Gallagher, perhaps one has to wrap up at this point, ignoring all that happened between Fresh Evidence and 14 June 1995 [RR: 🙄]. But that part of his life defines his way of being, that genetic resolve that he had to never give up, to always keep going forward with his plans: to be himself and create his own music. His mental health problems are palpable throughout his career in his lyrics. He recognised in Guitar World in 1993 that he felt exhausted and couldn’t find any reasons to be enthusiastic: “Success, failure, honour or oblivion, they mean nothing to me.” He lived, or rather he let time pass, for almost two and a half years, in the Conrad Hotel in London and gave memorable concerts at the Cork Jazz Festival, Montreux and Lorient, despite not enjoying performing like before and then suffering the consequences of the effort for days after. 10 January 1995 in Rotterdam was the beginning of the end. He struggled on stage, his liver problems no longer had a cure. He fell into a coma, they gave him a liver transplant, he contracted MRSA and, in the end, on 14 June 1995 at 47 years old, Rory Gallagher died – a death that could be reflected in the words of Jimmy Page: “Rory’s death really affected me. I learnt about it just before going out on stage and it spoiled that night. Although I can’t say that I knew him well, I remember meeting him once in our offices and we spent an hour talking. He was a very friendly guy and a great musician.”

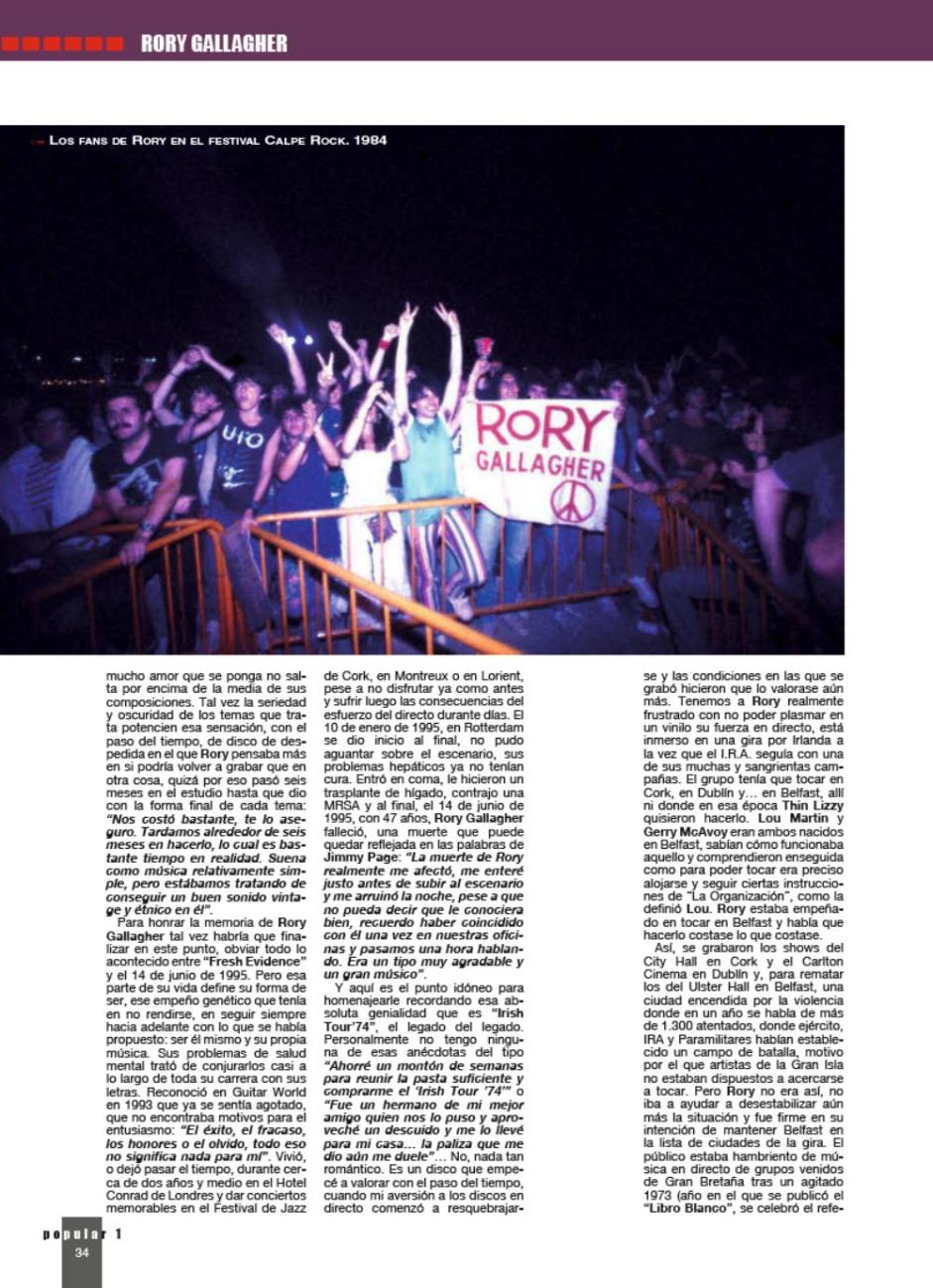

And here is the ideal point to pay homage to him remembering that absolute genius that is Irish Tour ‘74, the legacy of the legacy. Personally, I don’t have any of those anecdotes like, “I saved up for a tonne of weeks to get enough money to buy myself Irish Tour ‘74” or “It was the brother of my best friend who put it on for us and I took advantage of an oversight and took it home… the beating he gave me still hurts.” No, nothing quite so romantic. It is an album that I started to appreciate with the passing of time, when my aversion to live albums started to decrease and the conditions in which it was recorded made me value it even more. We have a Rory really frustrated at not being able to recreate a vinyl with his onstage energy. He is immersed in an Irish tour at the same time as the IRA continue with one of their many and bloody campaigns. The group had to play in Cork, Dublin and… in Belfast, where not even at that time Thin Lizzy wanted to play. Lou Martin and Gerry McAvoy were both born in Belfast, they knew how it worked and they understood immediately that to be able to play was precisely to follow certain instructions of “The Organisation”, as Lou called it. Rory was convinced to play in Belfast and he had to do it no matter what.

So, they recorded shows at City Hall in Cork and the Carlton Cinema in Dublin and to top it off, those at the Ulster Hall in Belfast, a city ablaze with violence, where in a year there had been more than 1,300 terrorist attacks, where the army, IRA and paramilitaries had established a battlefield, the reason why artists across the island were not willing to go there and play. But Rory was not like that. He wasn’t going to destabilise the situation even more and he was firm in his intention to keep Belfast on the list of cities to tour. The audience was starved of live music from groups coming from Great Britain after a troubling 1973 (the year in which the White Book was published, the referendum on the status of Northern Ireland took place and the Sunningdale Agreement was enacted…) The risk was evident and Gallagher perhaps was not totally aware that he was not only a musician, but that he could have become a potential target, for himself and because in his group there were also English people [RR: Welsh actually].

Gerry McAvoy remembers that his own family had moved to England after having been caught up in one of the many terrorist attacks in those days. Belfast wanted to see Rory Gallagher play and, whoever it was that achieved it, “The Organisation” and the others implicated had guaranteed that they would not compromise the security of the shows. So, despite the irregularity of the sound quality, due to the fact that there was no company who agreed to insure Ronnie Lane’s recording equipment (the Lane Mobile Unit), there is a connection between the audience and the band that transcends the songs, that floats above them and that turns into the heart that makes them beat. Rory and his band played from the soul at all the concerts. It didn’t matter that his mental health problems crippled him before his performances, that he paced up and down backstage, peeking at the audience through any gap, wringing his hands and perhaps drinking something more than he should, but he left them ‘A Million Miles Away’ and that commands absolute recognition.

They played for that audience because those offstage were his objective and his priority. Everything else (criticisms, musical negotiations) were mere accessories. He wanted it to be something great, so they got Tony Palmer to film the tour – he had already filmed Frank Zappa in 200 Motels and Jack Bruce and Leonard Cohen, and capture that environment visually. One must remember here that Rory considered the visual part of the music a complement, it could never be the main motive.

The band was at a point of quality and union seldom seen. The variety of emotions, of sounds, of details, of abilities are so complex that they become so simple as to pass unnoticed and it is only by listening over and over again that it reveals itself.

Behind the fiery opener ‘Cradle Rock’ hides an enormous anxiety of starting at the top, knowing that they are in Ireland gives that extra emotion that is underlined between every note, between every wink. The skill of Rory and the band is there, and as usual, it is Rory’s charisma above all else that leads. Technicans praise the tone variations of his guitar; they are a point of envy for other guitarists, and ‘Walk on Hot Coals’ is one of those examples that demonstrates it. The soul of Gallagher had a physical presence in his guitar etc. etc., in the notes that he pulled from it, like in ‘As the Crow Flies’ or ‘Who’s That Coming’. If ‘Tattoo’ Lady’ doesn’t transmit an emotional universe to you, there must be something wrong with you. This album, in its original version, has as much electric discharge as personal adventure in which the quartet of Rory, Gerry McAvoy, Rod de’Ath and Lou Martin were on the stage making Irish and musical history, without even knowing it, but what they transmit is unrepeatable.

Irish Tour ‘74 can also be seen from a more romantic point of view and why not? Less objectively, it is the album that reflects how, for a few hours, there was a handful of Irish and English [sic] musicians led by a little Irish genius, guitarist, who took the time to make all the differences between their audience disappear. The best epilogue perhaps is the words of another Irish genius Gary Moore who described Rory perfectly: “He was such a purist. He would never sell out. What people do you know in the music business who would adopt that attitude? If there were not people like Rory Gallagher to give that type of example, it would probably mean the end of quality music.”

Leave a reply to A Year in Review: 2024 – REWRITING RORY Cancel reply