Magic for the Ears

Directly from the magic of the musician’s fingers. The start of his pathway to the blues. The best magicians never reveal their tricks. And the longer the introduction, the better the magic.

More than 50 years have passed since Deuce was released, Rory Gallagher’s second solo album, and as if the passage of time was the long presentation of a great magician, that album is unbeatable magic. To celebrate such a huge achievement, we contacted Gerry McAvoy and Rory’s brother Dónal Gallagher.

Before the battered Sunburst Stratocaster, Gallagher’s fingers started to settle on an Elvis Presley model ukulele. Gallagher was nine years old, and he had preferred to have the Lonnie Donegan model, the most famous figure of the popular folk movement known as skiffle. In the Gallagher household, they lived and breathed music. There was their Irish heritage, of course, and a musician father who had a band, the Inishowen Céilí Band. Dónal Gallagher, Rory’s younger brother and manager, producer and friend, guardian of the legacy, tells us in 2022: “It was Chris Barber and his band who introduced jazz to Ireland. The only person who played the banjo was none other than Lonnie Donegan. And Chris Barber’s band went to the United States, above all to soak up the environment, and also to do a few concerts. And it was in the United States where Lonnie Donegan discovered skiffle and brought it over here. And it was largely the type of music that people played in the community: concerts that took place in local areas to help, for example, a neighbour to pay the rent. Things like that. Something that grew from a very strong sense of community. Music to make you happy, to make you dance. And the connections are really interesting because part of Lonnie Donegan’s ancestors came from Ireland. That is a connection. And, for example, in Ireland the mark of the Basque Country is enormous (Dónal remembers his concert in Irún with Rory at the Frontón Uranzu). We are Celt populations who come from the same branch. And it is something that you can tell in the music. When you travel, how natural everything feels. There is a common heritage that unites us. And when in 1955, Lonnie Donegan had a big hit with ‘Rock Island Line’ (recorded before prisoners in Arkansas in 1934, and by Leadbelly in 1937), he became Rory’s hero.”

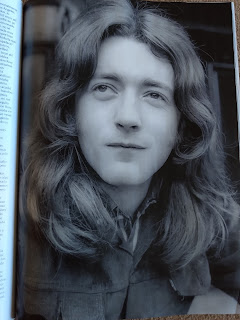

At 13 years of age, Gallagher plugged into electricity: a Rosetti Solid 7 with a four-watt Little Giant amp. When he was 15, he got his 1959 model Strat, without a whammy bar, but with a perfect neck to play slide. Dónal Gallagher reveals to us that: “Rory’s debut as a professional was in Spain, with a Cork showband, the Fontana. He was 17 years old. He had just finished his exams. They were playing at an American base in Madrid. It was very strange because they arrived there at the same time as The Beatles. Rory wanted to go to the bullring to see The Beatles, but he didn’t know how to drive and none of the others, who were older than him, were interested in the Beatles. Another thing that Rory had to do to travel to Spain was cut his hair. There were rumours that you couldn’t get into Franco’s Spain if you had long hair. So, the others in the group told Rory that he had to get his hair cut. And it was the first time that Rory had had his hair cut in years! He wasn’t happy at all when they took a photo of him getting onto the plane. He didn’t want anyone to recognise him with his hair like that. He was thrilled to play in another country with a group, and above all, to play for Americans. It was almost like going to the United States itself. In Ireland, when we lived in the North, near to Derry, Rory had got to know lots of music thanks to the American base that was there. He would tune the radio, which captured the signal really well, and that’s where he discovered jazz, primal blues, people like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, all those troubadours.”

After forming Taste in 1966 at the same time that Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience came out, and splitting the promising and powerful trio (with them, he performed at the Isle of Wight in 1970, along with Hendrix, and did a US tour with Clapton’s Blind Faith), Gallagher rehearsed with Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, Hendrix’s old mates, but ended up with Gerry McAvoy and Wilgar Campbell, two Irish musicians from the band Deep Joy who had opened for Taste on numerous occasions.

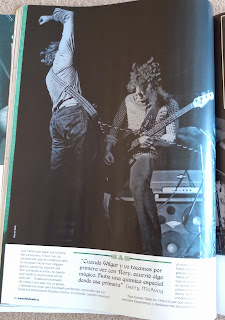

Here, Gerry McAvoy joins us, talking to This is Rock in 2022: “I was a fan of Taste. I went to see them in Belfast and with Deep Joy, we opened for Taste in London, and in other cities in different countries. But when Wilgar and I played for the first time with Rory, something magic happened. He helped me to be a guitarist too because from the start, I sensed a little where Rory wanted to go. And that was mutual. He also guessed my intentions. It was strange. There was a special chemistry from that first time that the three of us rehearsed together. It was a rehearsal, improvisation, I don’t know. It was always easy for me to work with Rory. That first time was, above all, playing all the famous blues and rock & roll tunes, a bit of a test, but in my mind, I remember something magic: being there in that small studio with my friend Wilgar, playing with no one less than Rory Gallagher!

As soon as he went solo, the cards in Rory’s hands had all sorts of different and changing suits. They were not gambler’s tricks, but magic stemmed from curiosity. Of course, there was the blues of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, of Leadbelly and Lonnie Mack. The blues that came after with Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton. Jazz. And there was also roots of skiffle: linking Lonnie Donegan with the North American tradition of Woody Guthrie. There was some classic heritage, the name of Andrés Segovia being particularly noteworthy. And like Tony Iommi, Gallagher had huge admiration for the Gypsy guitarist with the damaged hand, Django Reinhardt. Something curious behind Gallagher’s very unique use of the plectrum with the nail of his thumb and index finger: he had an accident, around 1965, where he shut his hand in a car door and his thumb nail never grew back normally again.

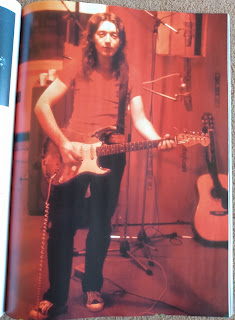

As for equipment, there were variants and additions: first, the Vox AC-30 amp (the same as The Shadows), also the Stramp (German, used by Leslie West). The Sunburst Stratocaster with the Fender Twin Reverb was consolidated at the start of the 1970s, as well as the Fender Bassman and the Deluxe (in those years of rock with the Marshall pyramids). Guitar, hand and amp, with Fender Rock & Roll strings and Herco Heavy plectrums. For acoustic, for those folkie moments, a Martin D-35 and a National steel guitar to play slide.

On Gibsons, Gallagher told Steven Rosen in 1974: “I don’t feel that at home with them. I’m obviously a very Fender musician. I love the metallic clarity that you can get with a Strat. Even playing with a small amp in a huge band with brass, though a Fender might not be loud enough, it always peaks through.”

“The naked guitar”, basically, with minimal effects, playing with the volume and the tone control, and with the plectrum and finger, to create harmonics from which unexpected sounds emerge, the result of the geniality between strings: with sounds that are hard to define, sometimes close to loops and synth samples, that you can get lost listening to.

Deuce

After an interesting debut in 1971, the homonymous album Rory Gallagher, a much more experienced trio recorded their second album Deuce just a few months later. On the first album, Rory Gallagher had played the sax like in Taste, and his brother Dónal had invited Vincent Crane from Atomic Rooster (a band that Dónal represented) to leave his organ aside for a moment and play a few songs on the honky tonk piano. However, the LP Deuce was completely centred on the power trio made up of Gallagher, McAvoy and Campbell. Dónal Gallagher tells us here: “Deuce was very important for Rory. Largely because he recorded it in a studio that was falling apart, Tangerine, in a very dangerous area too. But Rory didn’t care about this at all. Rory practically specialised in playing in studios that were on the point of falling down. It was the same with Olympic Studios, where the Rolling Stones recorded, and which in its day rivalled Abbey Road in terms of fame, and then Against the Grain was recorded in Wessex Studios, which George Martin built. After, Chrysalis bought it. That time, they were going to refurbish the studios and Rory insisted and insisted to Chrysalis that he wanted to record there. The recording stretched on and the people who were going to install the new equipment arrived, and Rory hadn’t finished! He had the idea that he couldn’t lose the energy of those places just like that, that you couldn’t let them tear out all that old equipment just like that. Six or seven studios closed after Rory was the last to use their installations. In the case of Deuce and Tangerine, he knew the guitarist from The Tornados, who had recorded Telstar, a huge hit for Joe Meek. And he was absolutely captivated by the stories he heard of Meek.”

Gerry McAvoy describes to us more about that moment: “It was just a few months after recording the debut that we went back into the studio. The big difference with Deuce was that we went from a luxury studio in London to another one that was pretty dilapidated. We recorded in Tangerine, set up by Joe Meek, the eccentric ex-producer, and that’s because Rory wanted somewhere more homely and down to earth. That’s why we went there. On the debut, Rory Gallagher, just after Taste, Rory was finding his way a little, and he put on all the music that he liked, all those different facades of blues, jazz, folk and rock, even some pop. When he composed the songs for Deuce, I think that Rory had a new confidence, after what happened with the debut. And he created some songs that sound incredibly fresh today.”

“Deuce was recorded while they were touring and doing concerts. On that album, there was only the three of them. And Rory wanted to promote this message: a trio playing good songs. And part of the album, we recorded after doing a concert that very night. We went in the middle of the night to the studio and we played with the adrenaline of the concert. The energy of the album comes from that. We recorded as if we were playing on stage.”

The first song on Deuce, ‘Used to Be’ was not too different from the dynamic start to the debut with the instant classic ‘Laundromat’. The second song didn’t take long to show Rory’s acoustic and folkie side, as he had done on the debut with ‘Just the Smile’. Although that was a very nice song, ‘I’m Not Awake Yet’, the second on Deuce, is even bolder. Rory Gallagher starts playing and singing as if he were in a dreamworld (curiously, Joe Meek was said to visit those oneiric worlds to create impossible sounds), half awake, and when the agile bass lines of Gerry McAvoy start up, we don’t know if they are saying to him, “Wake up!” or if perhaps they are asking Gallagher to continue towards a fantastic, brilliant world. Whatever the case, it is a magic moment.

Gerry McAvoy explains to us: “The chords for ‘I’m Not Awake Yet’ are very folk. G minor, but what is very interesting is how the song was recorded. Rory was in the booth with the acoustic, when he was usually outside, and he started to sing with that somewhat whiny, calming timbre, you know (sings the chorus). On the other side, the drum was in the room. They were like two parallel jams. The rhythm section, us, playing very powerfully, and on the other, Rory there, singing more peacefully. Like two opposing forces. On the one hand, that more folkie part of the 12-string acoustic, and on the other hand, a sharp hard rock rhythm section, but that strangely ends up amalgamating with each other. Something strange. I don’t exactly know what Rory was intending, but that’s how it came out.”

Rory Gallagher’s acoustic side continues with ‘Don’t Know Where I’m Going’, reinforcing his image as a troubadour on Deuce. Alone in the face of danger, he is accompanied by the harmonica. For someone who embraces music so fully as Gallagher does, the sound of the harmonica or the sax was a sort of intermediary with the instrument of the guitar: like a musician who blows on his fingers to create magic. Those fingers that played notes that knew how to speak, guitar notes with that same hoarseness as Gallagher’s voice. Gerry McAvoy: “On the first album, Rory was trying things out. With Deuce, he had passed that test of the debut, but he still wasn’t clear on where he wanted to go. He knew more clearly what his path was, but I think that with that song ‘Don’t Know Where I’m Going’, he meant that he still didn’t know his destiny. He had an objective with Deuce, but he didn’t know if his ideas were going to work or not.”

“Like Bob Dylan, Rory was not a harmonica virtuoso, but it was all about being expressive. Do you invite someone to play this part? I think it is more sincere, more direct, if you add that harmonica arrangement instead of a piano or another instrument. As a saxophonist, Rory was pretty amazing, to tell you the truth, but for him, the main thing was always transmitting emotion. He didn’t ever try to be a virtuoso with the sax or the harmonica. He always played from the heart.”

‘Maybe I Will’ starts with some chords that are raw emotion. Alternative rock that prefigures the alternative rock that would come some years later. And the magic of Rory Gallagher’s trio is that, when the rhythm section kicks in, instead of something closer to Neil Young, we are hit with something that flows with jazz. But it is not a style or a musician asking you to remember his name because he is so good. Rather, here, the musicians meld into the feelings that a song like ‘Maybe I Will’ transmits.

Although the young Rory Gallagher was upset about receiving an Elvis model ukulele and not the one of his idol Lonnie Donegan, as his brother Dónal says: “He had the idea that rhythm should be like heartbeats, like the Buddy Holly song ‘Heartbeat’. And who he focused on a lot for this was Elvis Presley. Rory said that Elvis’s drums always went a little behind, propelled by Elvis, giving life to everything. Rory changed drummers several times and I think that this was very important for him: that the rhythm section was something that flowed like that, with him propelling it.”

‘Whole Lot of People’ sees the first irruption of the slide. In this song, Rory Gallagher starts like a sort of stowaway on a night train of the blues. He hasn’t paid the ticket, but when he slides along the neck of the guitar, he has turned into the train driver. Gerry McAvoy tells us: “When we rehearsed that song, Rory’s chords surprised me a lot. It is not exactly blues, rather pop. They remind me a lot of 1960s US rock songs. I think that Rory has not been recognised as he should for his slide playing. He was fantastic. One of his idols was Muddy Waters, and on the albums that we recorded, he always liked to put some slide in. On Deuce, there are a few songs. He liked to do it. And on ‘Whole Lot of People’, Rory never came in with papers, nor did he tell you what you had to play. He let you make it up as you went along, and I added some rock lines into this song, which seemed to me the way it was going. It was my first attempt and Rory liked it. But, on the other hand, that song could have been a folk one. I also imagined it very clearly with Rory composing it alone on the acoustic, with those classic folk chords (hums). When he took the song to the studio, the folk mixed with the rock of my bass, the drums of Wilgar, and then Rory added the blues slide. We were doing something pretty new and, as I said, without any previous clear plans, no sheets of music. Everything emerged from that first moment. There was trust and excitement. That pushed us forward.”

In the following track ‘In Your Town’, the trio melded together until they all practically became a train. A machine that arrives in your town on a “Saturday night”, as the lyrics say. And that above all, carry a message: if you get on this blues train, if you start to wiggle to the music, you can escape here. Gerry McAvoy: “Yes, that song is like a train. It is great, when Rory showed it to us, he started to play the intro, that has that boogie rhythm, and that time Rory continued, continued with the intro and he didn’t stop. You should have seen Wilgar’s red face, not knowing when the change was finally going to come! (laughs). But it comes, and when it does, after all that initial tension, it has that point of liberation, of breath. And it is an invitation to dance, yes, and to leave the place where you are, physically and mentally. Because you have entered into the song. It was fundamental that the song transmitted something like that. And it become one of the most requested songs at concerts, one that fans particularly liked. Everyone got up and started to dance. An infectious song, a very good song.”

Dónal Gallagher adds this about his big brother’s composition: “‘In Your Town’… it’s interesting because that song inspired ‘Jailbreak’ by Thin Lizzy. Phil Lynott got the idea from hearing it because he speaks about this, of escaping from prison, referring to those 16 or 17-year-old guys who they were putting into internments in Northern Ireland. Rory absolutely hated special effects or lighting, but with ‘In Your Town’, we always put on a spectacle to finish the concerts. Very suspicious that our light technician then went to work for Thin Lizzy! (laughs). Rory and Phil were friends, and Rory felt flattered.”

As for the next two songs on Deuce, Gerry McAvoy – bassist on all Rory Gallagher’s albums – tells us: “Deuce is a very varied album, also very rocky on the one hand. With ‘Should’ve Learnt My Lesson’, Rory wanted to compose a slow 12-bar blues, and that’s what he did. A return to his roots. I think the song was a message to the record companies, about how things were handled before. ‘There’s a Light’ is stranger. I see it as psychedelic jazz, with that intro… Rory was a big fan of Love, Arthur Lee’s band. The drums are very jazzy, with a constant pounding, creating a background hum.”

The end of Deuce is a fertile contrast of extremes. The character that Gallagher has developed on these songs, with music that tells you about history, has many twists and turns. We could look at the titles alone, where Gallagher is looking for something very expressive: the acoustic ‘Out of My Mind’ indicates a solitary bluesman who can get lost on introspective journeys. Dónal Gallagher speaks about the reflections that his brother had as a lyricist, someone who was always looking to the sky, and who poured out feelings and stardust onto paper, like Antonio Vega: “Brother Guy, the Vatican astronomer, is a big fan of Rory. He saw him live in 1969. A while ago, I sent him the lyrics to the song ‘Follow Me’ because reading them again, I got very emotional. It is as if Rory was talking from the other side, almost predicting his death. And in another like ‘Moonchild’, there is a really special link with the cosmos.”

Compared to the intimate and solitary penultimate song, the final track ‘Crest of a Wave’ is the band pulling out all the stops together at once because if you want to ride on this “crest of a wave” of the title, you need the band. Gerry McAvoy: “Rory chose the songs right at end. He did things with deliberate intention. In this case, to finish the album, you have two songs that could not be more different. ‘Out of My Mind’ is simple, folkie and blues. ‘Crest of a Wave’ is very good pop and rock. It is going from one extreme to another.”

The extremes don’t just end with Deuce. They also characterise the entire career of someone so special and unclassifiable as Rory Gallagher.

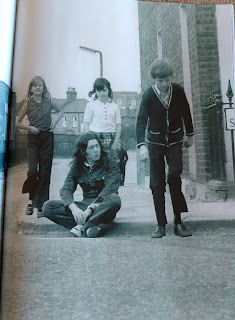

The Long-Haired Rebel

Dónal Gallagher: “In the beginning, when he grew his hair long, people picked on Rory in the street. They told him off and even spat on him. Once, I couldn’t take it anymore and I hit a guy. I knocked him to the ground. I was expecting Rory to join in. We loved play fighting, boxing. But that day, Rory shocked me. He told me that I was flying off the handle, that it was just what those troublemakers wanted.”

Some of the decisions that Rory Gallagher made in his career unsettled many. Incorruptible artist? Owner of an otherworldly wisdom, more connected with the underground waves of music? Or perhaps simply a long-haired rebel who wasn’t going to play by the rules. The maximum example of this came in January 1975, when Rory Gallagher was offered an opportunity to join the Rolling Stones. Keith Richards had stated before, when setting up the Stones’ own label, that there were two artists that they were clear that they wanted to sign up: Peter Tosh and Rory Gallagher. In addition, Gallagher’s profile was similar to that of Mick Taylor, who they needed to replace. An added bonus in the Irishman’s case was his special affiliation with country, which was something that Richards was particularly interested in delving into further.

Gallagher went to Rotterdam, where the Stones were camped out. And he got into their limousine, took part in the sessions where they played tunes like ‘Start Me Up’ and ‘Hot Stuff’ and he knocked many times on the door of Keith Richards’ suite. Keith was comatose over those days, and although he eventually woke up, he didn’t utter a single word to Mick Jagger, as the two sides were at odds. Rory Gallagher was signed up to do a tour in Japan (where the Stones were banned, and at that time, Gallagher and the Stones’ global sales were not that different). Dónal Gallagher tells the whole story today with a nostalgic and humorous exasperation, from his perspective as brother and manager: seeing an artist refuse to enter through the open door which possibly would have resolved his life. Dónal specifies Rory Gallagher’s final word in the Stones’ episode: “respect”. Respect for his Japanese fans. Rory said that he would not let them down, that he would not cancel the tour because he was considering joining the Stones. He left with the experience of having played with them and that was that!”

Rory Gallagher treated his fans with a folkie familiarity, inherited from skiffle. On the same level, looking directly in their eyes, at the same height. To then play music that makes you levitate, but all in step. And Dónal tells another anecdote that perfectly paints Gallagher in the Rolling Stones circus: “Rory was a big fan of the Stones. Especially of Brian Jones, also because of the link with Alexis Korner, with that blues tradition. It’s funny: he said no to the Stones or let the opportunity pass him by. But he ended up becoming good friends with Alexis Korner. They often met up to play and I remember once in Germany in a place that was packed. And the two of them went out onto the street because there was a lot of people who had gathered outside, and they started to play there, to prevent any altercations. They plugged into a streetlight, and they started to play skiffle and blues. In the end, many people came out into the streets. It was magic.”

Another legendary and surprising moment for Rory Gallagher came in January 1978. When he attended the last Sex Pistols concert in San Francisco Winterland. After that concert, the guitarist decided to throw away what he had already recorded, an album that was going to be the follow-up to Calling Card, an LP that had marked a change in the Irishman’s trend: he had hired an external producer, Roger Glover, to start. In those sessions in San Francisco, Gallagher was being produced by Elliot Mazer. He had the full backing of the multinational Chrysalis. But the whole project was aborted. And the definitive impulse for the drastic decision was Gallagher seeing the Sex Pistols. His brother Dónal shines a light on this legendary anecdote for us: “The possibility of working with Elliot was something that came up at the end of the 1970s. The singer Jake Holmes came from the United States and he opened for Taste (Holmes, composer of the original ‘Dazed and Confused’, also on that tour too was Stone the Crows with the ill-fated Les Harvey, electrocuted in 1972). Holmes was accompanied by Elliot Mazer, who was his producer. Rory and Elliott got on very well. Rory also liked the group Area Code 615, who Elliott was involved with, who did very good country. For contractual reasons, the plan to record with Elliott in the United States was postponed. Then Elliot coproduced ‘Harvest’ by Neil Young and the idea continued… When he was finally available, Elliott had dismantled his studio to record ‘The Last Waltz’ by The Band, and although he tried to put it back together for Rory, things just didn’t click in those sessions. Rory got quite upset. He could see that it was all taking too long…”

And then, after a Christmas break back home, when he went back to the United States, the guitarist saw the Sex Pistols and decided to take a huge swerve in his career: no outside producers, back to the trio format of Deuce, change of drummer. What Rory told his brother about that concert was the following: “I don’t know if I saw the best or worst concert of my life. But I loved the attitude that the Sex Pistols had. As for the music, it was terrible, but the energy, the way of performing to the public, it was like going back to garage music.”

The task that Rory left to his brother Dónal was tremendous: he had to appear before 53 executives who had gathered in London to tell them that the album they had sold as “Rory’s American disc”, the one that was going to help him triumph à la Harvest had ended up in the bin (literally, as Dónal told us). Then, Dónal had to make a lightning trip to San Francisco and back to tell Elliot Mazer face to face that Rory wasn’t going to carry on with the album and pay him the bill. To top it all off, Dónal then received a phone call from London telling him that Rory was in hospital, without giving him any more details. After a few minutes of worry, Dónal found out the almost comical truth, all in accordance with Rory’s unique character: whilst his brother was trying to put out the fire with the record company and travelling kilometres across the world, Rory had gone to the cinema to see the film Renaldo and Clara by Bob Dylan. And, after, he had ended up shutting his hand in a car door, in this case, a taxi. He had broken his thumb. Now, Dónal had the extra task of telling the record company that, as well as having their album investment thrown in the bin, they had to wait a few months before the guitarist would be able to play again.

A little after that Sex Pistols concert, Rory Gallagher and Johnny Rotten shared beers flying to the Macroom Festival in Ireland. But then there was a scandal created by the music press, particularly NME, where they tried to present Rory Gallagher as a symbol of the “old guard”, an anti-punk. As Dónal says, “It was disgraceful. At least people like The Clash spoke up and said that if Rory was anything, he was the king of punk.”

Years later, a last tail end of punk was the explosion of Nirvana. Looking from the outside, the attire of check shirts and the obsession with battered guitars carried a bridge to the “king of punk” that The Clash had spoken about. But, above all, when Kurt Cobain presented ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night?’ by Leadbelly on Unplugged, there was a connection with Rory Gallagher performing ‘Out on the Western Plain’, also by Leadbelly (Taste had already recorded ‘Leavin’ Blues’). His brother Dónal talks about this link: “The two drank from the same cup. And Kurt had saw Rory in Seattle. Cities like Portland and Seattle, being so far to the Northeast, were left out of many important tours. But Rory always went to play there, and the people really appreciated that. Once I read that Courtney Love said that Kurt had gone to see Rory several times, that he liked him a lot. And of course, if you see the check shirts… and there is a coincidence. My eldest son, Eoin, is a huge Nirvana fan and I remember that when he was little, Rory often to come to ours for Sunday lunch and the topic of the conversation once was Nirvana. My son told him all excitedly how brilliant he thought Kurt Cobain was and Rory had that connection with him because he understood. For my son, Rory was a different adult because of that. ‘Will the circle be unbroken’, like the Johnny Cash song.”

Scenes of War and Peace

The first album strictly played by the Rory Gallagher two was Deuce (“two”, “draw” and even “peace” in slang). Immediately after, in 1972, his first live album came out, Live in Europe, and then Rory the composer practically disappeared, limiting himself to two of his own songs, ‘Laundromat’ and ‘In Your Town’ and the others were jumping on the stage and the trio losing themselves in the blues, in folk. Rory Gallagher always rejected being a purist, a blues academic. He didn’t care so much about credits on an album as capturing emotion. When he started up the traditional ‘Goin’ to My Hometown’ on the mandolin in Live in Europe, the crowd breaks out accompanying him with claps and foot stomps. It is a magic moment of blues and folk, of skiffle (the style encouraged creating rhythms with kitchen utensils so that the music was not far away, but rather something very similar to what you had on the table, the harmony of a life of work and union). On this, Rory Gallagher said to Beat Instrumental in 1971: “I have always listened to the blues, and not a day goes by when I don’t put on a blues album. For me, Lemon Jefferson or someone like that is like a plate of food on the table. I feel a huge emptiness inside me if I don’t listen to that music. It is impossible to overstate the importance of those masters because they created music that we listened to in those days.”

In the end, if you want to get to know the complete rhythm section of ‘Goin’ to My Hometown’ on Live in Europe, you should learn the names of all those in the audience, as well as Gerry McAvoy and Wilgar Campbell.

Dónal Gallagher: ‘Goin’ to My Hometown’, my memory is that Rory started to play the mandolin and the song emerged naturally. And the rhythm is like heart beats. A quite unique syncopated rhythm, on the other hand. Something that can’t come from anywhere but deep inside, the simplest way. And that invites you to move your body in the simplest way too. That arrangement of the traditional song is Rory wanting to amplify the range of instruments that he played. Like when he played the alto sax. He also liked Bill Monroe a lot and country with mandolin. The lyrics are very rooted in Cork. Henry Ford’s great-grandfather emigrated from Cork, and he said that when he became successful, the first factory that he would build in Europe would be in Cork. And he did. And anyone who went from Cork to the United States could find work in the Ford factories. An uncle of ours went to Detroit and working there paid for his studies. He ended up being a physicist. That’s where the line in the verse ‘I got me a job from Henry Ford’ comes from. Closing a circle, in the version of ‘Goin’ to My Hometown’ on Wheels Within Wheels, Lonnie Donegan plays. And it is skiffle in the sense that people around 1972 were not doing well in Ireland. There was a lot of poverty, a lot of difficulties. And the response to that song at concerts was tremendous. It became a sort of hymn for young people. People trembled with it. When everyone started to clap their hands and stamp their feet, it was almost military. But not to divide, but to create the feeling of a united people.”

Gerry McAvoy on ‘Goin’ to My Hometown’: “The record company wanted it to be a single because it was so popular. But Rory didn’t like the idea of releasing singles. The participation of the audience in that song is what really makes it come to life. A small mandolin, the simplest drums, bass… only those materials. A few elements, and you can perfectly hear the entire crowd playing in that song.”

A few words from Rory Gallagher himself on his interaction with the audience at concerts from Beat Instrumental in 1971: “I like people to listen and have fun too. There are some artists who get annoyed if the audience makes a racket. But I think that if you start tapping your feet, that adds to the rhythm. And when you add to the rhythm, you start to listen to different things in the music. I really like to create that.”

And about the exultant close to Live in Europe ‘Bullfrog Blues’, where Rory achieves the trick of illusion by vanishing so that the bassist and his drummer do two short but incredible solos. Gerry McAvoy tells us in 2022, 50 years later: “We never rehearsed the solos. They were things that just happened. That is the pleasure of that music. Rory started up and we just played.”

To explain the energy of Live in Europe, a disc that goes hand in hand with Deuce, a studio LP with the adrenaline of a live show, it helps to remember a concert in January 1972: when Belfast was a war zone like Ukraine is today, during the Troubles, Rory still went there to play. Dónal Gallagher: “No. No, we weren’t scared to go there. We were only scared of being kidnapped, which happened very frequently then. In our family, we knew what division was. Our father was from the north, from Derry, and our mother was from Cork. When my father tried to get work in the south, it was impossible because he was from the north. So, he went from Derry to England, Coventry and Birmingham… but my mother wanted to go back to the south. We went with her, which led partially to the break-up of the family. Meanwhile, we knew about all the problems that young people were having in the north, how they were arrested in the middle of the night and locked up. That created a lot of anger. Rory didn’t want more divisions. He went to Belfast with the force of his songs, bringing emotion to the people. And now they are going to put a statue of Rory in Belfast, and the two sides are in agreement. Actually, it was the unionists, “the others”, who asked for the statue. Rory was conscious of the role that he could play, and he acted as a bridge.”

“The situation in Ireland was terrible. We were really thankful when Paul McCartney came out with ‘Give Back Ireland to the Irish’. And John Lennon also recorded ‘The Luck of the Irish’ with Yoko in 1972. I was able to thank Lennon personally once in Los Angeles. Anyway, the most difficult thing was going there and not irritating anyone in a heated environment. And Rory achieved that. I don’t really know how. Since he was little, he always had tremendous wisdom, which astonished me.”

Gerry McAvoy, originally from Belfast: “It was fantastic to play there during The Troubles. It was dangerous, but Rory said to go. And we started to go every year. The first time, the division between Catholics and Protestants was at its worst. But at the concert, there were people from both sides. There was no hatred under that veil of music. I was very proud to be able to play there, with Rory, when nobody would play in Belfast, And the light that you saw on the people’s faces was incredible. They were hungry for music. I have fantastic memories of that concert.”

The reviewer of the Belfast concert for Melody Maker, Roy Hollingworth, spoke about attendees who hadn’t left their homes in three weeks because of the climate of explosions, fire and violence. People who hadn’t returned home late after a concert for a long time. And it would still take a long time before they went to another concert. Hollingworth gathers statements like the following from promoter Jim Aikin: “Things like that give you feelings that nothing else does. If we can still put on a rock concert, it can mean nothing but good.”

Also, words like these of Rory Gallagher: “As soon as the moment of thanks for coming to play for them passed, they got into the music. It was a marvellous thing! They are fantastic kids, you know.”

The journalist Hollingworth: “I’ve never seen anything quite so wonderful, so stirring, so uplifting, so joyous as when Gallagher and the band walked on stage. The whole place erupted, they all stood and they cheered and they yelled, and screamed, and they put their arms up, and they embraced. Then as one unit they put their arms into the air and gave peace signs. Without being silly, or overemotional, it was one of the most memorable moments of my life.”

Before those people in the crowd who wanted to have fun, the magic was present that night on stage, with Rory Gallagher playing with his band in Belfast. From the top hat of the musician came a dove of peace. Naturally, without tricks. With courage. And the music took flight.

Folk Torch

Folkie guitarists like Martin Carthy, Bert Jansch and Davy Graham considered Gallagher someone who drank from the same spring of traditional music. This is very well represented in the compilation album that Dónal Gallagher put together in 2003, Wheels Within Wheels. Gerry McAvoy: “Rory always played the blues with an Irish touch. It had to be like that: he was a big fan of traditional folk bands like De Danann and Clannad. Sharon Shannon… even on a cowboy song like ‘Out on the Western Plain’, in the version that Rory plays, you can hear the Celt and Irish influence. That also happens with Van Morrison, Gary Moore or with a song like ‘Whisky in the Jar’ by Thin Lizzy, which is a traditional piece. There is a common thread in all those artists, without doubt. And this continues with Johnny Marr from The Smiths.” There is a funny anecdote of a teenage Johnny Marr taking advantage of his tech class to give his first guitar the “worldly” peeling finish of Rory Gallagher’s guitar and he almost caused a fire with the blowtorch. That really is carrying the folk torch!

“Jailbreak” in Spain

Dónal Gallagher: “I remember many things about our visits to Spain. The first time in 1974, Barcelona and San Sebastián, Madrid, and a few years after, Bilbao, Gijón… For Rory, tours were a sort of holiday to learn about different cultures. He really liked to try different foods, beers, talk to people, blend in. He read up so that he understood the political situation of each place, so that people saw that he understood the things they were talking about. Rory gave much importance to learning. He was fascinated with things. Like a fan, just like the fans!” Josema Martínez who organised concerts from the Centro Musical Irunés, remembers a night in Irún in 1979: “After a concert in Frontón Uranzu, we went to have dinner. It was all very pleasant, but we didn’t stop drinking. We both got extremely drunk. We stumbled our way into the Hotel Alcázar and headed to the lift. It was one of those old ones with an extendable iron bar and that opened on the other side. I remember that when we reached our floor, we both tried to get out the same way as the entrance, which was impossible. We fell onto the floor laughing and couldn’t stop. We didn’t even know why. We were lying there laughing for a long time like we were possessed. I don’t know how the story ended up or how we got out, but someone must have helped us.”

Band of Friends

Gerry McAvoy: “We are going to keep doing concerts with Band of Friends, in Germany, France, England, Ireland… we hope to go to Spain in January. A short while ago, we were at a festival in Cazorla. Very nice! The start of Band of Friends was strange. When I moved to France a few years ago, I went back to my LPs and my record player after a long time without putting them on. Of course, in my collection were Rory’s albums. And listening to those songs again, it was a music that was so alive… I felt that the next natural step was to put together a band to keep playing those songs. In 2012, I found the right people. The Dutch guitarist Marcel Scherpenzeel, the sadly deceased Ted McKenna. Now I have Brendan O’Neill, who also played with Rory between 1981 and 1991… and we also have the guitarists Jim Kirkpatrick and Paul Rose with us. We are preparing our first album to come out in February. Almost all the songs are original and a few Rory interpretations.

Leave a comment