Today we continue our exploration of the Rory Gallagher Band’s performances at four European festivals in the summer of 1994. Last month we covered the Pistoia Blues Festival (July 2) and the Montreux Jazz Festival (July 12). In Part One, we established two aims we hoped to achieve by posting this article: firstly, creating a definitive account of Rory’s appearances at these four festivals, which has been absent in past Rory literature; and secondly, resisting the familiar narrative that Rory’s musicianship declined alongside his physical decline. For Part Two, we apply these aims to our analysis of Rory’s appearances at the Festival interceltique de Lorient in Brittany (August 9) and the SDR3 Festival in Stuttgart, Germany (August 21). In preparation for this post, we had the opportunity to speak with Breton musician Dan Ar Braz and photographer Nathalie Simon, as well as concert attendees.

FESTIVAL INTERCELTIQUE de LORIENT (Inter-Celtic Festival of Lorient), 9th August 1994

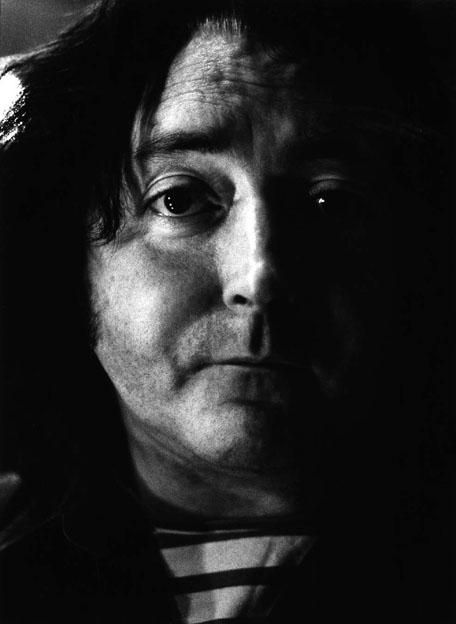

The above photograph was taken minutes before Rory took the stage in Lorient 1994. I admit that it is a difficult photograph for me to look at, and at times I might avoid clicking on it if I see it on the Internet or scrolling through social media. When writing this article, I forced myself to confront this image, and in doing so realised the source of my unease. It’s not the photograph itself, but rather the contrasting emotions when watching the concert. Onstage, Rory is all smiles, brimming with vitality, even joking between songs (for instance, his endearing introductions in broken French). Meanwhile, offstage, this photograph shows a portrait of a man who has lost his smile, overwhelmingly tired – even confused – and haunted with sadness and vulnerability. When researching about this show, three different perspectives of Rory represented through media and first-hand accounts stayed with me. All three sources build the image of what a complex man Rory was, from compassionate and respectful (first), to crippled with physical ailments and exhaustion (second), and finally the robust presence he left his audience with (third).

The first is from Nathalie Simon, an official photographer for the Inter-Celtic Festival from 1992 – 1996. “When I [took] pictures [of] Rory Gallagher, I was young [and] starting my job,” Nathalie told us, “and so certainly [that was] the most incredible highlight of my career.” She described the scene backstage for us, including the array of reporters, photographers, and journalists waiting in the hallway for Rory to leave his dressing room. When Rory personally chose Nathalie to take his picture, “the other photographers and reporters were furious, and were pushed back to the hall.” Although Nathalie spent a short few minutes with Rory, she revealed, “He took time to tell me some kind words to support me in my job. He seemed attentive to encourage me on my way […] [These are] words that I kept preciously in my memory.”

The second perspective comes from one of the many volunteers at the Inter-Celtic Festival. Patrick Kerihuel began volunteering for the festival in 1973, continuing to do so for another thirty-seven years. A 2010 article in the Breton newspaper Le Télégramme gave Patrick the opportunity to share some of his memories about the Inter-Celtic Festival, including seeing Rory in 1994. “His manager, who was also his brother, demanded that there should be no one between the stage and backstage when he performed. [Rory] had to be carried to the stage. He played for two hours flat out. Had to carry him when he came off.”

Finally, I turn to a review in Le Télégramme from 1994, which starts with a description of the anticipation from the audience’s perspective:

A control screen behind the scenes at Kervaric broadcasts a static shot of the door to dressing room no. 4 on which is affixed a sober inscription: Rory Gallagher. This door will soon open and on Wednesday, around 10PM, the roan bull storms onto the scene.

It is the storming “roan bull” metaphor that I latched onto the most during research for Part Two, and it’s what I immediately see when I watch Rory walk onto the stage at Palais Des Sports De Kervaic, his fists pumped and teeth gritted, immediately energised by the crowd’s affectionate welcome.

“The Irishman is King”: A background to Rory and the Inter-Celtic Festival

As we outlined in Part One of our introduction, information regarding Rory’s appearance at the 1994 Inter-Celtic Festival is scarce. This absence of acknowledgement is not only unfortunate in terms of Rory’s professional history, but also personal history, because being the proud Irishman that he was, we believe performing at this festival would have been a significant milestone for Rory. Despite the wide collection of academic documentation about the importance of the Inter-Celtic Festival for the Breton people, none of these sources mention Rory’s performance, and so we hope to contribute to the growing literature regarding Gaelic music culture. The Celts have inhabited Brittany since 6 BCE and survived many challenges, such as the Romanisation of its land and culture by Julius Caesar in 56 BCE, the British invasion across the 5th and 6th centuries, and retaining duchy against Frankish empires. In 1532, Brittany finally became part of France, igniting a struggle to retain Breton culture, language, and customs against the French. Music and dance was heavily centred towards Parisian traditions, resulting in a number of Celtic revivals since the Second World War. The establishment of the Bodadeg ar Sonerion in 1943 was highly important in the resurgence of Breton musical culture. Six members of the Institut celtique de Bretagne (Celtic Institute of Brittany) founded the organisation. (Note: this overview is terribly brief, and so we encourage those who are interested to research more about Brittany’s history, and particularly the work of the Bodadeg ar Sonerion).

In 1971, one of the members, Polig Monjarret (1920 – 2003), suggested the Fete des Cornemuses (a pipe band festival held in Brest since 1953) move to Lorient and be re-named the Inter-Celtic Festival. The festival offers the chance to embrace Celtic musical traditions and customs through events such as the Grand Parade of Celtic Nations; the Kan ar Bobl (or Song of the People), a contest inspired by Ireland’s Fleadh Cheoil; as well as concerts of traditional music and dance. The festival is celebrated across ten days at the beginning of August, and “is currently the most frequented folk festival in western Europe”, attracting musicians and audiences from Australia, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, and the Asturias and Galicia communities in Northern Spain.

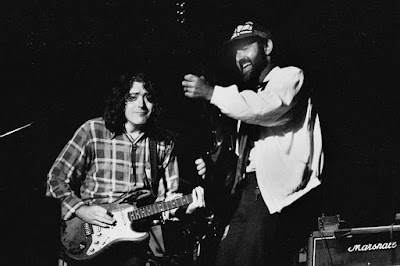

Photograph by Fanch Hémery

“What became of Rory Gallagher?” asked journalist Françoise Rossi in an article detailing Rory’s return to Brittany in 1994. Ten years had passed since Rory toured any of Brittany’s major cities (Brest in 1975; Quimper in 1980, 1982, and 1984; Rennes in 1980, 1981, and 1983; prior to 1994, Rory had never visited the town of Lorient). Rory’s frequent appearances in Brittany during the early eighties was particularly significant for Breton musician Dan Ar Braz, who had the lucky opportunity to befriend, as well as share the stage with, his musical hero. Dan has been a fan of Rory’s work since the days of Taste, and first met him in Montreux in 1975. Dan recalled his first impressions of Rory to be of “immediate kindness and simplicity,” and that to “be yourself” was “the lesson I shall never forget from that meeting with Rory.” In 1982, Rory played Quimper (Dan’s hometown), which would also be the place that Dan first joined his idol up onstage.

Rory played the “Salle Omnisports”. My friend Jean Théfaine, [a] journalist, wanted to have an interview with Rory and asked me to come to help for translation. So I did and took my new guitar with me to show it to Rory. So [we] went [to] the interview and, in the end, I dare [ask] Dónal if [there] could be an opportunity for jamming with Rory at the following concert. He said, “We will see then how it goes”. So I took my guitar just in case and [left] it [in] my car outside the place. The concert was warm and great and, towards the end, Dónal came to me and said, “You’re on” …

I had then to jump outside quickly to get my guitar that was so cold being in the car for so long. Got on stage and honestly I just remember being so happy to be on Rory’s side. I don’t remember how I managed sound wise and music wise, but I did my best … my playing was probably so weak compared to the fire set up by Rory. [But] yes I was so happy and so [was] the audience I hope.

Two years later, Dan and Rory played again onstage in Quimper, this time at the Stade de Penvillers. “We got to meet in Rory’s dressing room, [and] had a drink, two in fact!” Dan shared with us, “And later here I am once again onstage with him. That [show] was much easier for me, my guitar was warm enough this time!” As we have mentioned, following this 1984 concert date, Rory never travelled to Brittany again until 1994. “The 80s were not an easy period,” Dan said, reflecting to us about his “daily struggle from club to club” while continuing to practice and write music as much as he could. Eventually, his hard work led to the creation of the Héritage des Celtes, a fifty-piece group of musicians playing and celebrating Celtic music, their self-titled debut record (1994) selling one million copies. Meanwhile, we refer back to the question: “what became of Rory Gallagher?” We certainly know the answer (and the answer can be found on every post on this blog site), but according to Rossi’s 1994 article, the only things noteworthy is that Rory has “put on a lot of weight”, “doesn’t seem to be particularly well”, “hasn’t recorded for a long time”, “his bassist Gerry McAvoy is no longer at his side,” and “has remained loyal to his Canadian lumberjack shirts”. Although some aspects are negative and conform to the “people’s guitarist” theory (refer to Lauren’s paper on the mythologising of Rory in the music press), other points in the article are complimentary (“He is a musician who lets his instrument talk just as he has done since the beginning of his career” and “In the Celtic country, the Irishman is king”). The article concludes with comments from Dan Ar Braz, and his hope to join his idol onstage for just one last time (“this evening I am absolutely desperate to throw an amp and guitar in my car and get to Lorient”).

“He carried the torch of Celtic blues”: Rory at Lorient

When we watch Rory return to the stage for his third encore at the Inter-Celtic festival, dressed in his third shirt for the evening – which thirty seconds into “Messin’ With The Kid” would be absorbing more sweat – it’s hard to picture the man “[being] carried to the stage”. He bows for the crowd, he jokes with them, embraces the chanting of his name. The reviews from fans and critics alike are consistently positive, both from a past and contemporary point of view. This performance was not only significant in terms of being Rory’s first time in Lorient at the Inter-Celtic Festival, but that his appearance at the Kervaic generated a crowd of 4,500 people, a record breaking figure for the stadium, as reported by the newspaper Outset-France on August 12th 1994. “For the return of Rory Gallagher on the Breton scene … [it was] a hard, strong concert, built on rock, which we wish we heard more often.” From a twenty-first century perspective, other milestones achieved in this performance are mentioned, such as how Rory’s playing at that time fits into his career and life (as well as the epoch overall), as demonstrated by the analysis from a tribute blog post by user ‘Zantrop’ off the site Mediapart, “… we find a breathless and slightly puffy Rory … but who still has the energy and passion of unfailing virtuosity.” The author interprets Rory’s version of “Shadow Play” here as the blues man’s “swan song”, and which has the most “flavour of the nineties”.

The recollections of this concert that we encountered were all warm and loving. One YouTube commenter described watching Rory at Lorient as “the best concert I have ever attended,” making note of Rory’s “great generosity for his audience” and wonderful guitar playing on the night. Photographer Nathalie Simon (who we mentioned earlier in this post) had similar reflections. “Although it was quite noticeable that Rory seemed tired,” she began, “he gave a lot physically to give the best and this show was a great success.” Nathalie emphasised the crowd’s atmosphere, and how “particularly touching” it was to see Rory “delighted and grateful for” the “happy” and “heartfelt” response from the audience throughout the entire set. One of the best depictions of the unique interplay between Rory and his audience at the festival comes from a review in Le Télégramme de Lorient:

From now on it will be hand-to-hand combat. New encore, this one longer, and a frenzied rock with the sound raised to the limits of bearable, brings the floor to a trance. This hard core of fans aged 15 to 50 years old wants to push the singer to his last entrenchments but also to exceed his own defence limits.

Jumping to the present day, and I remember watching Rory’s 1994 Inter-Celtic Festival performance when I was just a new fan and not entirely familiar with his catalogue or life yet. “Continental Op” starts off the show with a bang rather than a whisper, the musical energy like a surge that feeds off the crowd wonderfully well. It’s a strong beginning to the hour and a half set, and I recall when first watching this concert with my father, sometimes we would just rewind this song over and over because it was such a captivating opening. Despite some tuning difficulties, the lively mood carries over into “Moonchild”, mainly due to the tight rhythm section provided by David Levy, Richard Newman, and John Cooke, before the tempo slowing down for “I Wonder Who”. Blues is more than just good guitar playing, but rather about creating an overall mood, and by this stage in his life Rory had mastered the art of story telling to sculpt that mood. He can paint an image for the audience with more than just his guitar, but also with his words, and similarly to Rory’s lyrical improvisation in “I Could’ve Had Religion” at this show, critics and biographers fail to take notice of his live musical progression. Again, the band is exceptional at following Rory’s every cue, from Cooke’s piano fill (like teardrops, so emotive) after “she pounce, and she cries”, to Mark’s harmonica work, which offers a nice contrast to Rory’s occasional notes on the harp during the introduction of this tune.

The mood turns upbeat and fiery with “The Loop”, followed shortly by “Tattoo’d Lady”. Then we get to “I Could’ve Had Religion”, which in my opinion is the highlight track from the electric portion of the show. Rory’s retelling of a corrupt preacher behind a swampy blues instrumental almost leaves a bad taste in your mouth – but in a very good way. Through adjustments in his voice, he’s able to encapsulate both the preacher (“I left my bible behind, left my suit and clothes behind”) and also the arresting officers (“They said, ‘Hey, preacher, why are you running in your skin? We’re gonna give you ninety nine days detention, we’ll rule out bail. Don’t mess with that girl again.”) His slide solo here is blistering, every note like a strike of defence; critics had similar descriptions, with Le Télégramme de Lorient’s review comparing Rory’s musicianship to warfare (he is able to create an “artificial hell”, and “his attacks are precise and powerful”). The Inter-Celtic version of “I Could’ve” is gritty and raw and, quite frankly, fucking rules, and so we find it highly disappointing that Ian Thuillier juxtaposed this version in the Ghost Blues documentary with anecdotes of how poorly Rory was physically and mentally, which only inferred to the viewer that Rory’s music was therefore poorly at this time too. It is twenty-first century accounts such as these that feed this weed in Rory’s legacy. We at Rewriting Rory have been dedicated since day one to putting on the gloves, removing (or rather pulling out) the rumours and the judgement (weeds) in order to cover (or mulch) the exposed ground with the truth – the balanced narrative. Moving on, the song “Ghost Blues” maintains this bluesy groove established in “I Could’ve”, and showcases brilliant solos from Mark and Rory respectively.

The acoustic set is flawless, as expressed by another review: “He carried the torch of Celtic blues rock very high. A truly magical night!” The version of “A Million Miles Away” is particularly passionate, and is highlighted by user ‘Chino’ on the French Rory Gallagher forum as one that “still gives me goosebumps” years later. “It was the only time I saw Rory onstage,” Chino wrote, and regardless of how “tired” and “in pain” Rory appeared, “I was taken by the passion and emotion that emanated from this concert.” Following the closing song (“Shadow Play”), Rory then returns for his first encore (accompanied by Dan Ar Braz), for a medley of “Don’t Start Me Talking” / “Revolution” / “Treat Me Nice” / “Dust My Broom”. Here is what Dan kindly shared with us about the experience:

This time again I phoned Dónal, and he said, “come on Dan and we’ll see how it goes”. Fortunately I came because it was going to be my last meeting with him …Well again I’m not very happy with my playing [as] the delay on my pedal board was all over the place and I didn’t know how to turn it down! But the true emotion was there and it is difficult to express it with any words …

Rory was very curious about my guitar and I sent him the brochure with all the details about that “Starfield” guitar. Rory that night slept in a hotel in Quimper “The Gradlon” and this was probably his last night in Brittany … Many years before, just facing that hotel, was a restaurant were we ended up with Rory after the concert in Penvillers and Rory, knowing I was struggling to make it as a musician, told the women who was my wife then, “his day will come …”

SDR3 Festival, 21st August 1994

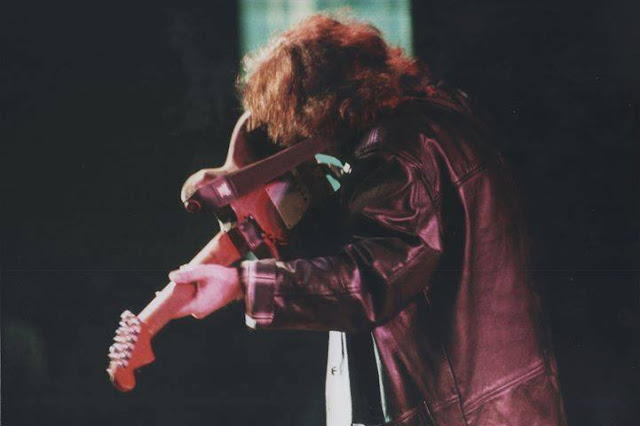

Rory’s performance at the SDR3 Festival in Stuttgart has always been close in our hearts. We briefly analysed the first song (“Continental Op”) from the Stuttgart set list in Part One’s introduction, in particular Rory’s strike towards the microphone and grazing his hand. Whenever I watch Rory in these later shows (specifically 1993 onwards), for me personally, he looks to be going through moments of mental distraction, almost as if he is caught up in the rush of the live experience. Although there are moments like this throughout all the festivals we have discussed in this article, these occurrences seem to happen the most at Stuttgart. Sometimes his solos aren’t as organised, or the improvisation is not as smooth, or the song introductions are a little disjointed. “[Rory had] also been put on steroids, which was absolutely the wrong thing for him,” Dónal Gallagher said in Ian Thullier’s 2010 documentary Ghost Blues: The Story of Rory Gallagher, “and it would swell his body, water retention, [as well as] messing his head up.” While we sadly see a few instances of Rory troubled onstage at the SDR3 festival (for example, following the first solo of “I Wonder Who” (IWW) and the beginning of “Tattoo’d Lady”), I think what significantly helps and lifts this performance is the support of the backing band. There are many musical highlights from all band members, such as the solid foundation provided by David Levy and Richard Newman on “Moonchild”. In fact, Richard’s drumming is consistently hard-driven and powerful throughout the hour set (check the drum solos on the interpretation of Ashton, Gardner and Dyke’s “Resurrection Shuffle”, and “Ghost Blues”) that it’s a shame, even upsetting, Rory fans (or critics) never seem to include him on their favourite list of drummers from Rory band line-ups – usually he’s absent altogether. When I listen to these late renditions of early Rory tunes, I don’t think of Wilgar or Rod or Ted or Brendan, I just think Richard and how he’s bringing his own flavour to the sound.

Stuttgart, Germany.

Photograph by Michael Heuer

In spite of Rory’s poor (mental and physical) health here, he continues to showcase intuitive leadership skill, such as directing solos to the band members in “IWW”. The point may seem simple, even a little obvious, but since it is so clear how ill Rory is at this show, it’s worth repeating how instead of the music disintegrating, it is still well rehearsed, unified, and complimentary. Rory’s lyrical improvisation and soloing on this version of “IWW” have always been a favourite of mine, though retrospectively the song is tinged with painfulness knowing what a dark period Rory was going through. The soloing from Mark Feltham and John Cooke adds light to the shade of Rory’s blues in this version.

Moving on, the band’s rendition of “The Loop / Resurrection Shuffle” is particularly strong and raises the audience’s energy up following the unhurried solemnness of “IWW”. Towards the end of his life, Rory is reported to have experienced pain and numbness in his arms and hands, as evidenced in the anecdote from Eric Bell in Julian Vignoles’ Rory Gallagher: The Man Behind The Guitar (“[Eric] says Rory complained of pain in his arms. Bell, who had experience of dependency in his Thin Lizzy days, said it was alcohol related. Gallagher agreed, he says.”). We can only presume that this symptom occurred onstage as well, ultimately impacting Rory’s playing. Throughout the Stuttgart performance, we occasionally notice Rory clenching and unclenching his hands between songs, such as during the introduction of “Bye, Bye Bird / Ghost Blues”. There is a sweet harmonica exchange between Mark and Rory on their brief rendition of Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Bye, Bye Bird”, and while bursts of passion and fire are present in Rory’s slide solo in “Ghost Blues”, the song (and entire set) is weighed down with lethargy. Nevertheless, this lethargy is utilised in a beautiful way for the acoustic set. Rory’s medley of Leadbelly’s “Out on the Western Plain” and the Irish traditional “Dan O’Hara” is – in my opinion – the strongest musically Rory is in the entire show. He seems to find the ‘feel’ of the music quicker and easier here than he does in the electric portion of the set, the transitions effortless in order to create a melancholic nostalgia. Following this, Rory and Mark play a medley of the hymn “Amazing Grace”, Son House’s “Walkin’ Blues”, and Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice (It’s Alright)”. The slide on “Amazing Grace” is clear and mellifluous, created by the Hawaiian twang from the glass bottleneck (Rory spoke about his slide technique in a recently unpublished 1991 interview with Jas Obrecht, which we posted last month with permission from Jas). “Shadow Play” closes the show, with one encore (“Bullfrog Blues”), though this is not included on YouTube uploads, only bootleg DVDs.

“Irishman is still a hit”: Rory in August 1994

Early on, it was extremely difficult to source fan testimony for Rory’s appearance at the SDR3 festival. Similarly, press reports and interviews are almost non-existent. To compensate, we then tried to fill in some of the gaps regarding other dates in Rory’s European summer tour, though again, this proved to be a frustrating process with little success. We were only able to source a newspaper review about Rory’s show at the Théâtre de Plein Air in Colmar for the Festival de la Foire aux Vins d’Alsace (or the Alsace Wine Fair). This festival runs throughout early August and includes trade fairs, music concerts, and showcasing the best Alsace wines. French singer Patricia Kaas and English reggae and pop band UB40 were the headliners for the festival; publicity for Rory’s appearance seems to be minimal, and his name is even absent on the promotional poster. Nevertheless, Rory and his band were indeed there, and according to the press, “the fifty year old [sic] Irishman is still a hit.” Rory’s show at the Foire aux Vins d’Alsace was a week prior to the SDR3 festival, and in spite of “a few wrinkles” he was able to deliver a “breathtaking” performance full of “energy, mastery, and feeling.”

When we set out on our investigation, the immediate question we asked was: what is the SDR3 Festival? As we have outlined, Rory literature reflects a poor effort of not only taking note of what festivals he performed at later on, but also what exactly these festivals are. SDR3 (radio for the wild south) was a pop radio station for the broadcasting corporation SDR, which reached the northern part of Württemberg-Baden. In 1989, SDR3 began annual hit parades (or the ‘Top 1000XL’ as it would be referred to), ranking the best pop and rock records twenty-four hours a day for five days (read this article to learn more about SDR3’s first hit parade). The hit parade in 1994 was a unique one because of the “participation of broadcasters in Sweden, Italy, the Netherlands, and Bosnia-Herzegovina” (SDR3 moderator Günter Schneidewind told us that this was inspired by the previously ‘Top 2000D’ program for German reunification). To celebrate the final day of the 1994 hit parade, a concert was scheduled in Stuttgart’s Reitstadion (an equestrian stadium that is occasionally converted for shows), and the main act was, of course, Rory. Although Schneidewind confessed to not remembering much about the day because “as the anchor man, I was in the studio and not on site,” he was able to watch the live television broadcast, and reveals “no one could have guessed that this would be [one of Rory’s] last concerts.” In 1990, Schneidewind arrived in southwest Germany to be a moderator and music editor for the East German youth radio station DT64. Despite the fact that “there were no records by him or Taste in the GDR […] Rory Gallagher was well known to music fans in the GDR in the 70s and 80s.” Schneidewind also shared with us that, “as a schoolboy and student, I absorbed [Rory’s] music with my friends and, as a teacher in the 1980s, I was pleased to see that some of my students were also fans of Gallagher’s music.” While we may have started off unlucky, by the final stages of our research, we were able to get in touch with another SDR3 moderator, Stefan Siller. Here is his memory of the day:

In 1994, it was quite risky to book Rory because – as we all know – he was not doing well. He was unable to appear for a two-hour live interview prior to the performance […] Our music editor Jogi Rathfelder, in consultation with the police, was able to get Rory to play an encore [“Bullfrog Blues”], even though the time window had already passed. Rory literally played his fingers sore: they bled.

In 1994, it was quite risky to book Rory because – as we all know – he was not doing well. He was unable to appear for a two-hour live interview prior to the performance […] Our music editor Jogi Rathfelder, in consultation with the police, was able to get Rory to play an encore [“Bullfrog Blues”], even though the time window had already passed. Rory literally played his fingers sore: they bled.

Currently we are in the process of getting in touch with Klaus-Peter Krippendorff to know more about the forty five minute program on Rory.

Photograph by Michael Heuer

When putting together this month’s blog post, there was one Rory lyric that kept buzzing around our heads as we wrote: I hit the floor, but I got up on the count of nine (“For the Last Time”). Written in 1971 about striking back following the break-up of Taste, this lyric, in fact, can be seen as a motto that guided Rory throughout his forty seven years on earth. No matter what life threw at him, no matter how much pain he was in or how many obstacles he encountered along the way, he kept going, kept persevering against all odds.

In that summer period of 1994, at a time when Rory was feeling particularly low, he played fourteen festivals across Europe. We have just had space to look at four in this two-part blog post, but hope to cover many of the lesser-known festivals in future posts, including Langenau, Thun and Geel. What has become clear from our research is that, despite a huge series of difficulties that would have floored most other people, Rory played on. He played on, at times with numbness in his hands or breathless from his asthma, his abdomen swollen and tender, his skin covered in psoriasis, his mind troubled. And not just played on, simply going through the motions, but played on as if his life depended on it, as if music was the antidote to his pain. And we suppose in many ways, you could say that it was. Music gave Rory a purpose, gave him a reason to keep getting up every morning, a reason to live. It was quite simply his salvation. But as musician and long-term Rory fan Johnny Marr mused in BBC Radio 2’s The Rory Gallagher Story, his salvation from what exactly, we may never know.

It has often been said that Rory felt he had concluded his life at this time. We hear it from Brendan O’Neill and Gerry McAvoy in the Gallagher’s Blues documentary, and even Mark Feltham has said as much when asked. However, this is not a view to which we personally subscribe. Rory had so much more to offer, so many goals he had yet to achieve. He was planning to finally record that long-awaited acoustic album and release it simultaneously with a new electric one. He wanted to write film soundtracks, design his own album cover, explore different musical styles, potentially collaborate with Bob Dylan, Martin Carthy, and The Chieftains. When Rory barricaded himself away in the Conrad Hotel following his collapse in January 1995, Dónal fought his way inside and confronted him directly with the question: “Do you want to die?” to which Rory replied, “No.” Naturally, he was frightened. Perhaps he couldn’t see a way out of the situation he was in, but, as always, he maintained that boxer spirit that Dónal has frequently spoken about, that boxer spirit that’s even the subject of “Kid Gloves” – the “master to beat” who’ll “fight anything.”

Rory was on the cusps of a new stage in his life. A new stage that had the potential to see him move in all sorts of exciting musical directions. The 1990s would have been kinder to him with their blues revival and a move away from the falsity and fickleness of the 1980s music scene. Energised by the youthfulness of his new band, Rory could have continued to headline large festivals or embark upon sell-out international tours, had he wanted to. Richard Newman noted in a 2013 interview with Pennyblack Music that the “phone was constantly ringing with offers to play huge stadiums all over the world,” so there was clearly still a demand for his music. Or he could have immersed himself in the folk scene instead and moved towards more intimate acoustic gigs like the one he gave at Cork Regional Technical College in honour of his uncle Jimmy in 1993. Or perhaps he simply needed to put himself first for once, take some time off and go back to Ireland, have his dear mammy fuss over him before deciding what to do next. Whatever he set his mind to, we know that Rory would have succeeded and made us all proud – just like he always did and still continues to do today.

In a 1991 interview with Seconds, Rory reflected melancholically:

There comes a point when you ask yourself what are you doing in life? I just want to be a good player who gets satisfaction from what he does, and be a happy person […] I can’t go away and vanish like some people want. They’ll have to find a slot for me somewhere […] I think that maybe in the ‘90s I’ll find a niche; if I never do, that’s okay.

Rory’s words are difficult to read, especially given that he never lived to see the fruits of his hard work and that, thanks to the tireless work of Dónal, it is only now that he has indeed found more than a niche in the annals of music.

For many, it would seem that Rory passed twice – physically in 1995 and metaphorically ten years earlier when people started to forget about him or turned their attention elsewhere, unable to handle his change in appearance and wrongfully equating this with a decline in musical ability. Our simple concluding message for fans everywhere is be kind. Be kind and love Rory as much in 1974 as in 1994. Yes, we know it can be hard to watch these later performances, that they might make you feel sad or even shed a tear, but remember that he’s still our dear Rory, our check shirt wizard, our red-haired king (as per the Celtic origins of his name). Still the same guitar virtuoso, the same incredible performer, the same humble, kind-hearted genius that he always was; he was just a little more bruised around the edges. But when all is said and done, just let the music speak for itself. After all, as Beethoven once proclaimed, music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy; it is the electrical soil in which the spirit lives, thinks and invents. For us, Rory epitomised those beliefs and that’s what made him such a unique and incredible musician in all stages of his life.

—–

We are extremely grateful to Dan Ar Braz, Nathalie Simon, Günter Schneidewind, and Stefan Siller for their input when preparing this post. If you are interested in reading the full transcript to our interview with Dan Ar Braz, please click this link.

Thank you for reading!

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply