A Bad Day for the Blues

It seems like yesterday, but it has already been 25 years since Rory flew away. Let’s remember him together.

The decision came many years ago. Better not to remember how many, I would get too depressed. The undersigned, who had Mephistophelically turned a passion into a job, who had long believed in what he had read and heard, threw in the towel. After tonnes of interviews that were always substantially the same, although I tried in any way to vary the approach, to find new topics, to throw myself into alien territories – for the interviewees I mean – to hope to obtain pearls of wisdom or illuminations on a new way of listening, of interpreting if not a lot of music at least the music produced by those in front of me, I decided that I would give up the pleasure of hearing myself answer trivially about what only rarely, in a very modest percentage, I was able to snatch from some lucid and well-equipped minds.

The problem was basically always the same: just as footballers, sportsmen with a gift, an immense dowry, always and only used common stereotypes in useless post-match interviews, musicians also hardly had that flicker which, during a chat, could lead you to learn something about the mental process, the culture, the meaning of life, the meanders of thoughts that led them to compose a great song. Because the gift of knowing how to play and compose rarely coincided with a clear, ready mind ironically; or at least in a few, exceptional cases, which I remember with affection and nostalgia, to tell the truth.

It was the same syndrome – which for some reason never affects sports journalists and their passionate readers – that surrounds those who interview footballers. The questions are horribly predictable and foreseen, not even predictable, but even when they shouldn’t be, the answers you get back are always the same … never a flicker of irony, a leap of the fence, the pleasure of letting us know that, beyond a great talent there is also a brain. Not at all: once nominated “the Coach” three or four times, the interview can be considered closed.

To me, with musicians, even with those I had loved for a long time, interviews almost always ended up being the same, obvious, promotional chat, where the purpose ended only with being there for the duty of signing, to obtain the cover or occupy as many pages as possible in the newspaper in question. So, I chose to keep the best memories of those who really had made me get up from that richer and more open armchair than the half hour before when I had placed my austere ass in front of the rocker in question and gave up, from that day, the pleasure of hope to many others.

This is not the place to make a list of those who I still love to remember today when I throw myself into the rare musical chats with friends who want to listen to me, nor to disappoint many who certainly would not want to be told that their idol was often not who they thought and sometimes you often change one of their sentences to something more logical in order not to make them look a freak, given the absolute inconsistency of the contents.

But thinking of Rory Gallagher, I am honoured to remember that the three times I found him in front of me I felt the thrill of talking to a musician as mythological as he was simple, accessible and unappreciated and who shared passions, interests, a real desire to speak to any of the passionate journalists he was talking to.

My first memory of Rory dates back to my youth, when in my city there was a place called Piper, a square building, a very low building that lies in ruins today and object in the following decades of a hundred projects never realised, located on the seafront of my town Viareggio. It was substantially more like a new nightclub than a concert club. But it was exactly on the opposite side to where I lived and from where, like it or not, it was easy to hear the notes of the rehearsal of whoever would play in the evening. And going to peek through the draped windows or listen to that evidence was a cost-effective habit. Especially since if you were lucky and the room had become too sultry inside, I remember that they opened a double emergency door on the sides and from there you could have a good view of the tiny stage where the older boys provided with the budget for the purchase of the ticket, in the evening would attend the real concert. We had a limited budget and our mothers didn’t always trust us to mix with those long-haired ones, but every now and then, when the figure was important, we tore the ticket to officially cross the waterfront boulevard.

I remember that with Rory the door was opened after a while and the volume was incredibly loud. But what came out of the amplifiers, that blues rock, the hoarse voice and never able to put the soloist in trouble … because playing and singing don’t always get along … prompted me, the next day, to buy my first record by Gallagher: Live in Europe.

But my first close encounter took place eight years later, in Reading, a charming university town where an annual festival was one of the unmissable appointments in musical England. In 1980, after midnight, when Rory closed the first day of the three-day festival, where he first exalted, then destroyed with his physical participation, finally silenced the sixty-five thousand fans of what in those days was called ” the new wave of English heavy metal “. Before him, in fact, we had seen Ian Gillan Band, Krokus, Nine Below Zero, Praying Manthis, Hellions and Fischer Z… a brilliant group that has never sold a record here. And in the days to come, all the cream of the current English metal scene would appear on the big stage of rock and roll.

I remember when the group walked offstage for what seemed like a mid-show interlude, Rory showed up with a stool and an acoustic guitar and played three songs in sequence. There was silence over Reading, except to hear the choruses yelled at the top of their lungs by studded rockers … and I too found myself yelling the chorus of Out on The Western Plain … Like a cow-cow … yicky, like a cow- cow..yicky yicky yeah …

Minutes after the end of the concert, backstage, a trailer was waiting for three idiots who were convinced they could really talk to Gallagher after such a tiring set. I for one was very doubtful, but I was wrong. Dripping in sweat, half-destroyed, attached to a couple of bottles of Four Roses and a bottle of ice water, Rory not only answered but went above and beyond any request, expanding and citing topics that no one would have dared expand on given the late hour that it was for fear of being thrown out abruptly. I only remember that a German spilled something on a tape recorder visibly cursing in his own language and that when I, a teetotaler, was offered a bourbon, I politely declined and got a box of orange juice instead. Gallagher looked at me with suspicion and amazement at first. Could there be a teetotaler rock lover? Yes, in my case.

Photographer unknown

I remember that the Irishman waited for the German to finish cleaning his recorder in order to continue speaking; a surprising gesture of courtesy. And I remember my 90-minute recording partially occupied by a few lines with Nine Below Zero’s Dennis Greaves before Rory almost apologised to tell us he needed to go and shower. I left that trailer with the certainty of having talked to a double, who one puts there to tell us about his passions, about the latest records bought, about the ones he liked and why, about the instinct… the only one … revitalizing punk that had pushed him to recover a rought trio, of the stimuli that these new heavy groups were also giving to his playing, but above all to his infinite passion for acoustic music, for the blues, for the greats with whom he had played and which he felt grateful for learning something and with those with whom he would personally pay to play. A 32-year-old boy with the passion and impetus of a sixteen-year-old; a real and tangible passion for music, very rare to feel so alive and emerging in an irrepressible way, especially if listened to by those who have been on stage for decades. And Rory was not drunk, despite the bourbon, nor under the influence of any kind of substance. Lucid and attentive, he only mumbled with that strong Irish cadence that often made it difficult for me to immediately grasp what he was telling us. On stage the speech was much more English, more effortlessly understandable …

And here it always comes to mind a consideration that only native speakers can express and that was told to me one day, at a U2 concert. A Scotsman told me: “It pisses me off that all those who sing do it in American, as if it were an international language… and when they find themselves in interviews or between one song and another, they speak with the accent of the place where they come from!. A reflection that I had never realised. And that since then has surprised me every time I happen to notice the two inflections of the Anglo-Saxons … an example I often remember, just the few words of introduction by Bono to Live Aid to his Bad and the accent with which he then sings the entire song. Funny.

The second time I spoke to Gallagher at length was at a festival, a few years later, but my last time is a nostalgic memory that my enthusiast’s mind refuses to recreate with clarity, as it was almost a long goodbye, which lasted part of the afternoon spent with him, his brother and half the band negotiating the arrangements for the television shoot in what was certainly the last Italian appearance of Rory. I remember that the first impression, the first little shock, was not so much seeing him not dressed in his characteristic plaid shirt, but covered by a black leather jacket, with a very normal blue shirt underneath, but seeing how the man had got fat and had the swollen face typical of those who have serious health problems and are taking large doses of cortisone. Exactly what was wrong with him, with reticence, I was told in passing after a first, quick interview. I remember that I always saw him attentive and precise in his requests – they were preparing the stage for rehearsals just as the crew was setting up the cameras – but his gaze was sometimes absent. A matter of moments, but a bad sign for a man of only 47 years old. And I still remember that since there was some problem precisely with the positioning of the cameras and that the director was momentarily walking around, to break the ice a little, I threw myself into telling about the meeting I had in the trailer in Reading with him and Donal, his brother/manager … to him, who must have seen hundreds of faces of young self-styled interviewers … But I was amazed when, after some initial uncertainty, Rory remembered the German who had spilled something on the tape recorder and it started to drip and of that guy who drank no alcohol but orange juice … ‘I don’t speak German, very well,’ he said, but since I often played in Germany, I remembered at least some of the bad words, and that man was saying really bad words!”

Photographer unknown

Almost heartened by the fact that he was discussing rights with someone he already had a car deal with, he said to his brother in a very thick dialect something that sounded a lot like a request to reach an agreement. Which happened regularly. During the afternoon he disappeared several times to return only in the middle of the evening, but every time we met, we were able to exchange about ten minutes of speeches on the blues which was the best music in the world but which, ‘like a wave of the sea’, came and went in the interest of enthusiasts. And it was a shame, from his shareable point of view. I had brought with me a couple of records that I wanted to have him sign, but seeing him so young and in such bad shape made me give up on the idea. I was a little ashamed and I felt like I didn’t want to be the vulture who asked for an autograph from someone who was about to leave us, as it happened.

Telling who Rory Gallagher the musician was now becomes superfluous; not only does his music speak for him, but you can find thousands of pages on the web to understand it. I can only tell you that Rory was one of those who lived to go on stage and that for the rest of his day he spent the time listening to music, talking about music, studying music. I don’t know if the legend behind Hendrix’s famous question is true … “How does it feel to be the greatest guitarist on Earth” … with the abrupt answer: “I don’t know: ask Rory Gallagher!”. It was in Wight, in 1970, a few days before Hendrix also flew away too soon, but one thing is certain: they both lived and breathed music and blues. Both were kind, respectful, sensitive and shy people, all characteristics that you will not find in many of their colleagues. Both have left a groove that, after more than fifty years, many guitarists still try to cross today. Taking up their songs and trying to give as best a version as possible, respecting who will be listening to the result.

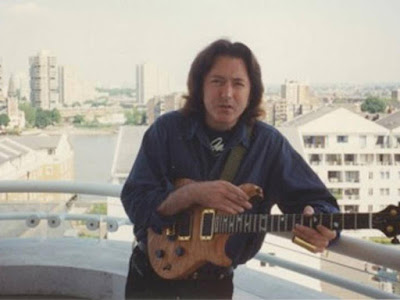

It is not important to tell you to get your hands on the few Taste records, or to listen carefully to the beauty of all his solo records; much more important is understanding the image of man. Because Rory was really a gentleman, despite being a provincial boy, rough enough not to love the manias of rock stars, but seasoned enough to understand what he should carefully avoid so as not to take that turn. A kind and courteous man who always spoke in a quiet voice and smiled broadly when the topic became particularly interesting for him. A public figure who didn’t pay much attention to appearance or haircut. A man who was always ready to suggest you something to listen to first if by naming a group or an artist your expression showed that you did not know what he was talking about, also giving you ample motivation. A genuine music lover, with the same approach that so many keyboard artisans should possess. One who in the last months of his life had left his Ireland to stay in the city centre, in London, where he had a house in Earl’s Court and from where he dreamed of returning to meet friends again.

Photographer unknown

The image of Rory in his last months is that of a lonely man, made even more shy than usual by his liver disease and medicines, a man who had lost confidence in what he loved to do. A man who lived close to Donal’s house, avoiding his own, sleeping in a hotel and using a false name. He who had loved Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler’s hard spy tales, was now experiencing them in real life. For some mysterious reason, he never returned to Ireland while making generous appearances on a number of Irish artists’ albums: the Dubliners, Phil Coulter, Samuel Eddy and Davy Spillane among others. Rejecting numerous concert offers, cancelling tours at the last minute and bonding in a binding relationship with Martin Carthy, a musician he called “Mr Positive”. With him and with Bert Jansch he planned to make an acoustic record. Jansch who remembered when Rory wanted to make a record with Anne Briggs, a legendary traditional Irish singer who, however, had declined the proposal, thinking she was wrong to confuse herself with what she considered a pop star. Rory, who for his entire career had almost always and only played his very battered and well loved Stratocaster.

Rory who loved Dylan and was impressed when he learned that his idol wanted to record a version of If I Could Have Religion with him on guitar. And it was a biography of Dylan given to him in hospital by Mark Feltham, his harmonica player, the last thing he read but who would have been honoured and amazed to learn that Bob Dylan owned all of his records, as Donal later discovered.

Rory recorded an interview for Irish television shortly before ending up in the hospital, destroyed by medication, according to his brother. On that occasion, he spoke of Belfast, of Taste, of the best years of his life. He talked about Bert Jansch, Davy Graham, Martin Carthy and ended the chat with a splendid “Celtic” arrangement of Elvis’s That’s Allright Mama.

Closing the circle and bringing it all back to Presley, where everything rock started. It was a bad day for the blues, that 14th June 1995.

The original article can be found here: https://www.rockaroundtheblog.it/ricordo-di-rory-gallagher/

Leave a reply to Posthumous Articles – REWRITING RORY Cancel reply