Click on this link if you missed our post earlier this month covering sessions from 1985 – 1991.

Today we continue exploring the topic of Rory’s session work, jumping to 1992 for our next session. In this edition, you will read comments and reflections from the many artists who worked with and admired Rory, including: Joby Fox, Kevin Breslin, Shu Tomioka, Pete Lockett, and Roberto Manes.

‘Barley and Grape Rag’, ‘Will The Circle Be Unbroken’

(recorded for 30 Years A-Greying by The Dubliners, 1992)

Since the beginning of Rory’s career, The Dubliners have closely followed. In a 1992 interview with Hot Press, Rory recalls his initial meeting with the group in his early adolescence:

We were playing a show with Dickie Rock and The Miami Showband in the Savoy in Cork. And because we were way down the bill, we weren’t even allowed to change in the dressing room. So we were out in the hall changing when Ronnie opened the door – The Dubliners were second on the bill so they had a room to themselves – and he said come on in and use our room with us. Luke was there and Ciaran Burke and all the rest and they were very nice. It was a small gesture but I’ll never forget it.

Over the years, the friendship between Rory and The Dubliners grew, ultimately leading to their 1992 session in London. The Dubliners’ 30 Years A-Greying celebrated their 30th anniversary as musicians, and similar to their 25 Years Celebration (1987), featured many special guests, such as The Pogues, Billy Connolly, Hothouse Flowers, and, of course, their good friend Rory. The first track Rory played on was a reworking of “Barley and Grape Rag”, which previously appeared on his 1976 release Calling Card. Rory adds plenty to the track, including harmonica, tambourine, and acoustic guitar, as well as sharing lead vocals with Ronnie Drew. In the 1995 documentary Gallagher’s Blues, Ronnie remarked upon the effect Rory had on him, claiming that he “didn’t have the overconfidence that the mediocre have, [rather] he had the quiet unassuming way that the great have – and he was one of the greats.”

“Barley and Grape Rag” is sloppily arranged: solos weave throughout, laughter creeps in-between phrases, and voices linger beneath the instrumentation. Instead of polished wood, the song is splintering bark, capturing the atmosphere of comrades rather than entertainers, and, as a result, us as the listeners feel personally welcomed into this wonderfully improvised moment of musical gaiety. In contrast, Rory’s harmonica playing on the country adaption of an old Christian hymn, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken”, showcases his great emotional flexibility, this time a sorrowful echo of the song’s lyrics: the funeral procession of the narrator’s mother. Rory’s use of the ‘wah’ technique imitates mournful cries, intensifying the duet between Irish singer Eleanor Shanley and Ronnie.

In his 1992 conversation with Uli Twelker, Rory expressed great passion to record a (long overdue) acoustic album, spurred on by his session with The Dubliners. “I get on with [The Dubliners] so well. Those people are so kind,” Rory added, contrasting the attitudes of the folk and rock world, “The folkies are a lot more caring about people. The rock guys have so much ego and so many bloody trips going on … Folkies are not into the big bucks.” Coincidentally, Dónal Gallagher revealed in a 2003 interview with Shiv Cariappa celebrating the release of Wheels Within Wheels, that he was supportive of the idea of Rory following “the acoustic thing” after parting ways with Gerry McAvoy and Brendan O’Neill in 1991, due to the fact that Rory’s “music tastes were changing and he didn’t seem to like the travelling element [of the rock lifestyle].” In light of this, Rory’s session with The Dubliners in 1992 gives us a strong beginning to a new musical pathway that, while prematurely concluded due to his untimely passing, showcases exciting potential, nevertheless.

‘Remember My Name’

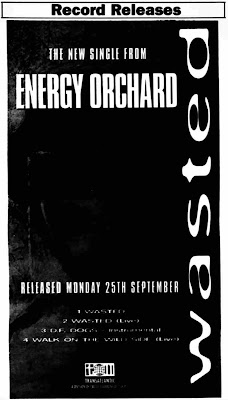

(recorded for Pain Killer by Energy Orchard, 1995)

“Rory Gallagher was a big influence in music in Belfast,” Kevin Breslin, keyboardist for Irish group, Energy Orchard, stated in our interview with him three weeks ago, “people had a great affinity with Rory, you know?”

From his brief residency in the early Taste days, to playing the Ulster Hall regularly throughout the Troubles, Belfast was a place close to Rory’s heart – and this connection was only strengthened as we delve deeper into his 1994 recording session with Belfast band, Energy Orchard. The group formed in the late 1980s, and after a few years of developing their sound through live performances around London, they released their first single titled “Belfast”, written by bass player Joby Fox. In the early half of April, we reached out to Joby to ask about Rory’s influence on the band, and he kindly shared with us his “electrifying [and] religious experience” of watching Rory perform live for the first time:

I was fourteen years of age, walking past the Ulster Hall in Belfast, and one of the security guys let me in to see what was going on and it was Rory and Gerry and Brendan O’Neill playing, and I was totally struck by the whole experience.

Three years later, Joby was part of a group called The Bankrobbers, whose debut single was, coincidentally, produced by Gerry and Brendan, an event that Joby described as “fatalistic”. When forming Energy Orchard with Bap Kennedy, Joby remembers, “Rory [being] around”, however, “I was star struck, [and] I wasn’t really able to talk to him … which is unusual for me to say the least [laughs].” Unfortunately, following the release of “Belfast” (1990), Joby parted ways with Energy Orchard, and therefore was absent on the session for “Remember My Name” with Rory.

Meanwhile, Kevin Breslin’s career in music began when he became involved in the group 10 Past 7 with Spade McQuade and Bap Kennedy. After performing around Belfast for a period of time, 10 Past 7 travelled abroad to London, meeting up with David (percussion) and Paul Toner (guitar). At this stage, Spade left the band to move to the United States, eventually replaced by Joby, this line up soon developing into Energy Orchard. Kevin recounted to us in vivid detail the DIY advertising surrounding one of the first Energy Orchard performances:

We decided to put a gig on in London … it was quite a large venue, [and] we rented it out ourselves and done our own promotion … [at first] it was just a poster, [which] didn’t say anything, it was just a poster of a waterfall … we put them everywhere and we dropped cards all over the subways, and then we let that run for a week. Then we [used] the same poster but [this second time] we put ‘Energy Orchard’ on it, and then we let that run for a week or two. By this point in time the whole of London was talking about [us]. So we done the gig … and it was packed, it was absolutely packed.

Belfast’s Sunday Life

To the group’s surprise, not only was this London show a success in cultivating an audience, but also watching the performance was musician Steve Earle. “His wife was a Vice President of MCA,” Kevin explained, “so we ultimately sang to MCA through that connection.” Energy Orchard would sign to MCA Records in 1990, achieving critical laud for their debut album and embarking on an extensive touring schedule. By 1994, the group had released two other albums (1992’s Stop the Machine, and Shinola in 1993), and as Kevin described, “we were becoming a musician’s musician band [due to the fact that] quite a few people [wanted] to play on some of our songs.”

One of these people included Rory, who, according to Kevin, “got a message through [to us] saying he would like to come in and play on one of the tracks. So of course we jumped up and down and went ‘yeah, great, brilliant!’” The sessions for “Remember My Name” occurred towards the final stages of what would be known as the album Pain Killer (released in 1995), with the entire evening dedicated to Rory to suggest and record whatever he felt suitable for the track. Kevin described Rory in the familiar high regard from anyone who had the pleasure of meeting him:

[Rory] was just a lovely guy. I call him the gentle man of rock n roll because he was. He was just such a gentleman. [During the 1994 session] he had this thing where you had to take your shoes off and the shoes had to go together a certain way, and then [he would say] ‘it’s good luck’. So I think I took my shoes off and put them the same way for him [laughs].

For most of the session, Rory stayed in the studio and made minimal visits to the control room, preferring to get as many ideas down on tape for the band to select from. Rory contributes guitar, harmonica, and Dobro to the song, each layer complimenting the initial rhythm track provided by the group. To Kevin’s recollection, the addition of the Dobro was Rory’s idea, which all members agreed lifted the song.

For the 2011 Record Collector article “The Man Who Sweated Rock N Roll”, Bap Kennedy briefly spoke with journalist Gavin Martin about the “Remember My Name” session, painting a dismal picture of Rory’s presence in the studio:

His guitar guy [Tom O’ Driscoll] turned up earlier in the day and brought a van rammed with amplifiers into the studio and arranged them in a big circle – gunfight at the OK Coral with the amplifiers. [Rory] couldn’t see over them, he just got into a circle, right in the middle of them, and went mad … bizarre.

Gavin Martin (purposely?) inserted this quote between the stories of Rory forgetting the riff to “Shin Kicker” during a rehearsal, unfavourable descriptions such as “looking like Jake ‘Raging Bull’ La Motta on his final 1994 Montreux performance,” and his ill-fated 1992 Town and Country Club show where Rory’s medication mixed badly with one glass of alcohol. As a result, if we are to rely solely on this account of the “Remember My Name” session, we as the reader (and, more disappointingly, the fan) fall trap to this negative (and misguided) portrayal of Rory as passive, inward, and even distant. Nevertheless, during our discussion of the session with Kevin, a different and – most notably – positive perspective is outstandingly evident, and the cracks within Gavin Martin’s argument begin to appear. Instead, the picture we find ourselves to be painting is of an active, collaborative, and unguarded Rory.

[Rory] took a break and came [into the control room and] started talking to me about keyboards he liked. He loved the Rhodes piano sound, and Hammond sound. He was really into that, chatting away. And then he’d go back [into the studio] and say ‘alright, let’s move onto another section’.

Although playing on another artist’s song, Kevin noticed that Rory “took a great interest in “Remember My Name”, and he wanted to make sure that what he was playing was not for the sake of playing, but that it worked out best for the song”.

gig at the Paradiso Club on 7th January 1995

Following a fruitful session, Energy Orchard crossed paths with Rory again in 1995 when they joined him on his final tour. Several months later, “the record label called me to tell me [that Rory had passed], and it was terrible. I was shocked,” Kevin recalls. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Kevin performed at the Rory Gallagher International Festival held every year in Ballyshannon, regarding this opportunity as “a great honour for me.” As we reached the end of our interview, we wanted to know what was one thing Kevin took away from his encounters with Rory during the last two years of his life, and the answer certainly makes us miss the man more than ever:

His energy level onstage was off the charts, and that’s one thing that will always stick with me … his whole attitude to music and performance was definitely just Rory, and it was just so positive. When we met up on the [1995] tour, he came round backstage, down the corridor, and he was just glowing. It was terrific to see him like that … you know, when he walked into a room, he just lifted the whole room.

‘Leaving Town Blues’, ‘Show-biz Blues’

(recorded for Rattlesnake Guitar: The Music of Peter Green by various artists, 1995)

In his official statement following Peter Green’s passing in 2020, Dónal Gallagher brought to light the bond between Peter and Rory, beginning in the Taste days, “My brother was very fond and an admirer of Peter, and they enjoyed each other’s company.” When attending a Doors gig at the Camden Roundhouse, Dónal recalled Rory and Peter engaging in conversation for most of the night, and so when news reached Rory in 1994 that Peter’s health was declining, he readily accepted the opportunity to pay tribute to an old friend. Rattlesnake Guitar: The Music of Peter Green was released in 1995 and featured an array of musical legends including Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson, Arthur Brown, the Yardbirds’ Jim McCarty, and Billy Sheehan. A portion of the profits generated from the sales of the album was donated to the Willie Dixon Blues Heaven Foundation, which was established in 1981 by the blues artist himself to help preserve the blues tradition and publications. In a retrospective review following the 2003 album re-release under the title Peter Green Songbook (A Tribute To His Work in Two Volumes), critic Michael Fremer praised the musicianship and production, claiming, “this record is not to be missed both because of the stinging performances and the superb sound.”

Shu Tomioka

As Rory always did when covering an artist, he made the songs his own. “Leaving Town Blues” originally appeared on the 1971 compilation album titled The Original Fleetwood Mac, which featured outtakes of the first line-up of the group from 1967 – 1968. The arrangement is minimal, with Peter Green’s soft vocals drifting in-between the fiddle melody and clear guitar line. In contrast, Rory updates “Leaving Town Blues” with multiple layers of instrumentation, from mandolin, to the Dobro, and electric guitar (Rory’s technique here on slide is powerfully screeching in some places of the track). Richard Newman’s use of the drum brush and prominent beat on the kick drum offers a hypnotic backdrop to Rory’s interweaving guitar lines, generating a bluegrass feel. Meanwhile, despite the maturing of his voice, Rory’s singing still showcases impressive emotional range, from a whimper (“Got the blues so bad, baby”), to a growl (“Operator, operator, operator”).

“Show-biz Blues” featured on the 1969 album Then Play On, which was the last Fleetwood Mac album with founder Peter Green. The original is poignantly arranged, with sweeping rhythm guitar, tambourine, and bass. Alternatively, in the 1994 version of “Show-biz Blues”, Rory, again, colours his version with layers of sound, including keyboards, electric guitar, tambourine and shakers, hard-hitting drums, and overdubbed vocals (3:41). Rory takes lyrical liberty quite heavily on this one, from the additional line “I swear on the good book that I’ll take no liberties” after “Baby, I would take you home with me,” to “If you wanna make this man cry, it won’t be hard to do” from Green’s original lyric “You want me to make a last cry, I’ll be satisfied”.

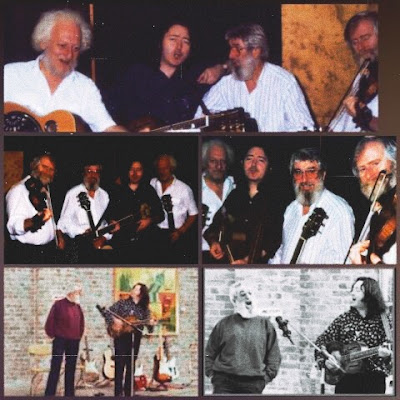

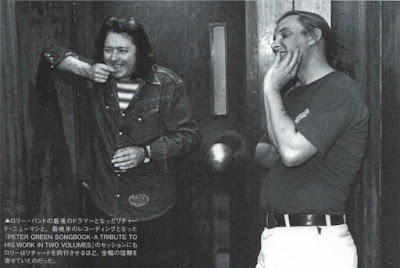

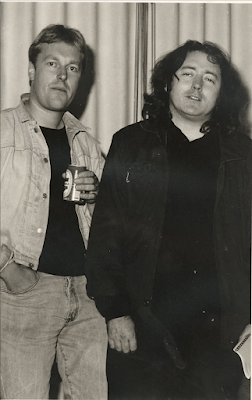

For many months now, Rory’s session for the Peter Green tribute album has been of great interest for us, but we were disheartened to find scarce information out there about these wonderful recordings. Part of the mystery was lifted when we ordered the book Rory Gallagher: 25th Memorial Edition published by Shinko Music Entertainment, which highlights Rory’s tours in Japan (1974, 1975, 1977, 1991). The final chapter of the book (‘In Rory’s Later Years’) showcases the photographs taken of Rory by his close friend Shu Tomioka, some of which – to our delight – were previously unseen images of the Peter Green tribute session. Earlier this month, we reached out to Shu Tomioka, and he graciously agreed to help us on our mission to gain further insight into these two tracks.

at the second session for Rattlesnake Guitar: The Music of Peter Green, 1994

Photograph by Shu Tomioka

Shu was born in Tokyo, Japan, and began his career as a freelance photographer in 1985. When moving to London in 1990, Shu would take pictures of many of the live acts he saw regularly, before getting in contact with the organisers of a benefit gig at the 100 club for the saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith and asking to photograph the event. On the night, Shu photographed a number of British musicians, leading to an article for Japan’s Record Collectors magazine about the show. Eventually, his own column called “Portraits in British Rock” was created for the magazine, which Shu has run since 1993 to the present day. As he shared with us, Shu’s aims for the articles are to “highlight some of the musicians who don’t usually take centre stage, yet make an enormous contribution to British rock.”

Through the benefit concert for Dick Heckstall-Smith, Shu made friendships with many names in the music world, including Cream’s Jack Bruce and lyricist Pete Brown. When Pete Brown was producing the Peter Green tribute album, Shu was appointed as the official photographer of the sessions. According to Shu, Rory came in on the second session for the album, which occurred at the Roundhouse venue in London.

On 30thMay, 1994, I met Rory face to face for the first time. Because he loved Japan we clicked immediately and had a nice chat. He was friendly and even invited me to visit him in [the] Conrad Hotel in Chelsea Harbour to make an article [for the “Portraits of British Rock” series] … In the dark area of the studio there was his beloved Stratocaster, white Telecaster, Dobro, 12 string Stella acoustic, old Japanese TEISCO guitar, and a flat mandolin. Rory kindly let me play his Stratocaster. That was like my dream came true … Later I became a good friend of [Rory’s long time roadie] Tom [O’Driscoll], [and] he told me that he was watching me playing the Strat closely in case I made a scratch on it!

Rattlesnake Guitar: The Music of Peter Green, 1994.

Photograph by Shu Tomioka

On the initial session, drummer Richard Newman joined Rory in the studio, and as Shu remembers, they were musically a “strong [and] powerful unit.” The second (and final) session was a month later on 18th June, and was primarily devoted to completing overdubs. On this occasion, keyboardist John Cooke was brought in, as well as two female vocalists. Shu recalled the name of one, Deborah Welch, who was on the chorus. On the official release, Rory did not include the female voices, though it is interesting to note Rory experimenting with vocal textures here, absent in his earlier studio work.

This session was harder and took a long time. Pete Brown and the co-producer John Mackenzie took Rory to a nearby pub for a break. Rory asked me to come along and I took the pictures of them chatting together at the bar. Rory also chatted to other customers at the bar who were keen to talk to him about his music. He was always happy to talk about his music with his fans whenever they approached him.

Also present in the studio was cameraman and close friend of Rory’s, Rudi Gerlach, who filmed parts of the session. On his website (now run by Volker Grupe), Rudi has mentioned that the session lasted well after he retired to his hotel room, with Rory slipping a note underneath his door that read he had just returned from the studio at 5:45 AM.

‘Falsely Accused’

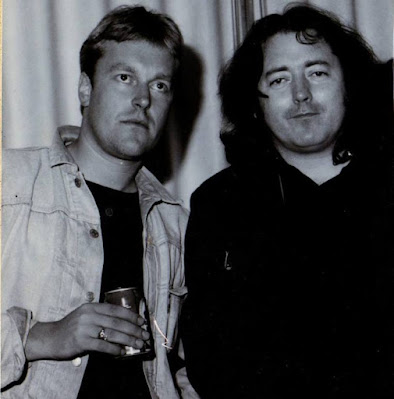

(recorded for Strangers On The Run by Samuel Eddy aka Eamonn McCormack, 1995)

As we began our research for this particular session, we discovered Rory’s impact on Eamonn McCormack to be undeniably clear, with the majority of his interviews mentioning Rory at least three or four times. Eamonn became an immediate fan at eleven years of age when he came across a Rory concert playing on television, “and I was blown away.” He first met his musical idol backstage at the 1982 Punchestown Festival in Ireland, with the two establishing a proper relationship a few years later when Eamonn was touring around America and bumped into Rory in Los Angeles. Later reflecting in December 1995, Eamonn admitted that “[Rory and I] became closest throughout the last six months of his life,” and between long phone conversations, Rory participated in one of his final recordings, which would be released in September of that year on Eamonn’s album, Strangers on the Run (later re-released on 2012’s Kindred Spirits under his given name).

concert in Bremen 1992, Photographer unknown

Strangers On The Run was Eamonn’s second release under his stage name of Samuel Eddy, and helped to establish himself as an artist in Ireland after touring across the Continent and America for many years. The first mention of collaboration between Eamonn and Rory surfaced publicly in Eamon Carr’s column for Dublin’s Evening Herald, where Eamonn recalls a rare day off from his band’s busy touring schedule in December 1992. “We crossed paths with Rory Gallagher in Bremen. We went to his gig and he was great,” Eamonn said. The two friends hung out following the concert, where Rory brought up Eamonn’s recent work with guitarist Jan Akkerman (both as a support act and in the studio) and teasingly asked “what about me?” The idea was left up in the air (“We might get together in Ireland, [but] we’ve got to sort things out,” Eamonn confirmed to Carr at the conclusion of his 1993 article), until a session was scheduled for January 1995, shortly after New Year’s Day.

In “Falsely Accused”, Eamonn coolly talks us through the injustice of “Billy Ray”, a man at the wrong place and wrong time during a hold up in a gas station and, as a result, becomes “suspect number one” to the police, despite the fact that “Billy Ray did nothing wrong”. The lyrics and mood allude to the many plot lines from some of Rory’s favourite detective stories and, therefore, it isn’t too surprising to us that he agreed to collaborate on this particular track. In a Rory interview from December 1994, journalist Jip Golsteijn conjures up a sensitive portrait of a man in physical decline (“a bit uncertain on his legs,” “difficulty composing a swollen face into a smile,” “his eyes don’t join”). However, on “Falsely Accused”, for someone clearly fighting a physical (and mental) battle, there is not a trace of evidence to suggest that Rory is in a musical decline. From trading fiery solos with Eamonn following the second chorus and towards the conclusion of the song, to providing electrifying suspense with slide interludes in the fourth verse (“silence in the courthouse, feel the atmosphere, jury passed the verdict …”), Rory proves that not only can he keep up with young talent, but thathe is still young talent himself.

In a 1995 interview for the Evening Herald, Eamonn shares with reporter Eamon Carr about the “tremendous experience” of watching Rory transform from a “shy, somewhat nervous” demeanour when arriving at the studio, to then putting on his guitar and “[becoming] larger than life.” Eamonn adds, “The whole studio shook with the sound. [Rory] was ten years younger. He was jumping around and you could feel the experience he had.” We as the listener can gain a sense of Rory’s enjoyment from not only his guitar playing, but his animated shouts in the background which echo a few of Eamonn’s verses (for example, the “yeah!” after “the DA won’t set bail,” or “alright!” after “some people are accused in the wrong”). Eamonn confirms in Carr’s article that Rory participated in every aspect of the session and showcased his wisdom in the studio, from “telling the sound engineer what graphics to change for sound,” to “pushing me on the vocals … he even changed a few of the words for me before I sang it.” As a final point in Carr’s article, Eamonn highlights the far-reaching influence of Rory:

It’s only when you travel that you realise how big Rory was, and how respected he was. He moved and influenced a lot of people to take up guitar. I don’t think he himself realised the impact he had on musicians, not just Irish ones, but throughout the world.

Photographer unknown

Despite passing away (almost) twenty-seven years ago, Rory’s impression on Eamonn’s life has not diminished. In a 2018 interview for a Dutch music blog, Eamonn was asked to name his favourite collaboration throughout his career:

Well, as always top of the list is my old friend and hero Rory Gallagher. Rory is always the most special one. I do what I do because of Rory. He owns a part of every note I play.

To commemorate the 25th anniversary of Rory’s death in 2020, Eamonn was invited to play at the International Online Tribute Concert, along with acts such as Dom Martin and Paul Rose. Eamonn told Blues magazine that he was honoured to be involved in the event.

‘Raga for G.M. Volonté’, ‘Voices From The Bazaar’

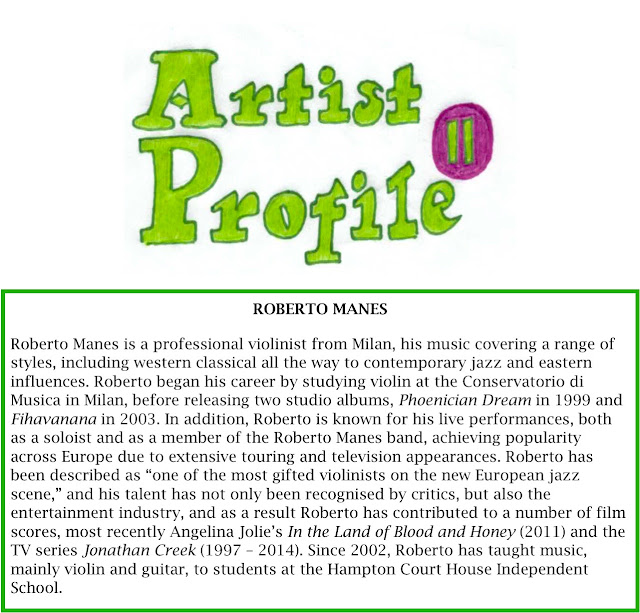

(recorded for Phoenician Dream by Roberto Manes, 1999)

On his 1999 album Phoenician Dream, Roberto Manes fuses violin with tabla percussions to create a harmonious blend of jazz, blues, and Eastern influences. On December 22nd 1994, Rory guested on two tracks for the album. Roberto shared his high praise for Rory in the album’s liner notes, describing him as “one of those rare people in whom art and life combine as one … [with] tremendous inner strength and belief.” Roberto added brief comments about the collaboration, reflecting on the contrast between how anxious Rory was in the studio compared to the “absolute calmness” he felt afterwards. Sadly, Rory passed away before the titles of either track were finalised, but he had told Roberto that he wanted to dedicate one of them (“Raga for G.M. Volonté”) to his favourite actor Gian Maria Volonté, who had passed away earlier that month, and the other to the spirit of a street market in Africa (“Voices from the Bazaar”).

November edition of The List,

issue 373

Since our first listen to these recordings, they have undoubtedly stayed with us, even haunted us, if you will. We didn’t know where to begin with our analysis, our minds carried off on this rich, musical voyage, and yet whenever we tried to pen these thoughts, our fingertips froze over the laptop keyboard. The music we heard was grandiose, yet organic, somehow foreign, yet addictively inviting. The chemistry between Rory, Roberto Manes, and percussionist Pete Lockett is explosive, very passionate and respectful, one talent does not dominate the other; together, all three elegantly fuse. We were entranced by how they crescendo as effortlessly as they simmer in “Raga for G.M. Volonté”, or how we could taste every flavour from spice, to grain, then dirt in “Voices from the Bazaar”. Every influence creeps into Rory’s playing, from Celtic to Delta blues to flamenco, and when combined with Roberto’s graceful lines on the violin and Pete’s fluctuating and expressive rhythms, the music created sharply contrasts to anything Rory had previously recorded. As we continued to listen and digest the sounds, our curiosity grew to the point of contacting both Roberto and Pete, eager to learn more about this collaboration.

To our excitement (and surprise), Roberto and Pete expressed interest in participating with our project. As always before our interviews, we were nervous. However, after a couple of minutes talking with Roberto, we discovered him to be extremely warm, the both of us simply in awe of his wisdom and enthusiasm to tell his story. We rarely had to prompt him with questions, one memory sparking a series of others, as we quietly listened. In 1990, Roberto relocated from his birthplace in Milan to London after he was offered a publishing deal with Warner Chappell Music. This presented many musical opportunities for Roberto, including forming his own band. “My style was jazz-rock fusion, so it was a band but it was instrumental, it wasn’t pop or rock with a singer,” Roberto tells us, and instead of a person, “the violin would be the singing part.” In addition to his group, Roberto worked on various projects at this time, including regular session work for television and movies, collaborating with artists in the studio, as well as joining a separate band to his own which covered American songs and featured a singer from Texas. It was around this time in the early 1990s that Roberto and Rory crossed paths.

So, [the band which covered American songs] we went and played in a club, a nightclub I would call it, in Fulham … uh, Fulham Road, and that’s where Rory Gallagher used to live. He had a little – on the corner there – he had a little apartment … But how we met was one night we had this gig in this club called The Polo, as in the Polo sweets, like that one. In fact, they had those little sweets on the bar as well

… So that club I think it just opened late, like it would open when the pubs would close … We would start and play at night, around midnight [or] one o’clock in the morning at that place … So what happened is that at that gig Rory was there … he was there for his enjoyment … [and] it was handy for him to come down from his apartment and just go there and have a couple of hours there. And I believe he enjoyed the gig, and particularly enjoyed my playing because after the gig we ended up having a chat. And of course I knew him from before because I knew Rory Gallagher – I even had [a couple of Rory’s albums] in my vinyl collection in Milan.

Roberto was unsure as to whether he was playing with his own band or the American covers band when he met Rory for the first time at The Polo. However, he recalls that he continued to see Rory at that particular club on different occasions, and Rory was complimentary on both bands Roberto was part of.

We clicked from the start … most of us when [we] meet someone new somehow you do connect or you don’t, most of us are like that, and in the case of me and Rory we alchemised entirely from the very beginning. I could feel he was entirely connected to me, despite the fact my English wasn’t very good … so it was beyond words, it was a connection on a musical level definitely; we had a similar way of doing music, especially the soloing.

One of the features from Rory’s musicianship, which Roberto strongly related to, was his natural sense of improvisation. “My violin playing has always been based on improvisations,” Roberto explained, which attracted him to the form of jazz, “and [on the Phoenician Dream collaboration with Rory and Pete] it was entirely improvised. We didn’t decide anything, which is like the jazz mentality, and it was one take.” Soon after meeting Rory, an acquaintance developed into a special friendship, which we could sense from Roberto’s words, was a friendship still very dear to his heart.

I asked [Rory] at some point if he wanted to come and join me [on the Phoenician Dream recordings]. I mentioned I had a friend playing the percussion [Pete Lockett] and I thought it could work altogether … I don’t remember whether I played him something before, [such as] previous recordings and then he heard the percussionist, or he just trust my word and then he popped in with his guitar. I don’t remember exactly how I present [the idea] … but he did come. It wasn’t very early [in the day], but he did come [laughs].

We sat amazed hearing Roberto’s details about this “smooth” collaboration, from the close privacy of the studio (“It was just Rory, Peter Lockett, the sound engineer [Andy Fryer], and me”) to the talk outside the studio, “in the corridor [and] office doors, [because] they were aware that we had Rory Gallagher … because he was quite a legend, I would call it.” Roberto continues:

We didn’t rehearse or anything … I allowed Rory – of course, he was the guest, and I want to be the host – and I said ‘you go, you start’, and we follow you, I follow you, Pete follow you … So we just follow, and create the sound together. And I think Rory was the only one who did a couple of overdubs afterwards, but not because of mistakes, just because he wanted to add. He wanted to add some slide guitar and then he wanted to have some harmonica, [which] you will hear at some point .

[Rory] was very kind. I would even use the words tender and sweet. But a couple of times … I did see him upset. And I remember once he even called me in the middle of the night, [and] he wasn’t too impressed with Warner postponing the release of what we did. He wanted to have it happen. Actually, he wanted to get them to help me more. And I remember he find me possibly [a] very soft type of person, but I perceived him as a soft person, but then he told me in the middle of the night … ‘Roberto, sometimes we have to get tough’. So I suppose … if he was disappointed, he could tell you.

Roberto remembers Rory as “also very clever, intelligent, curious, [and] a cultural person.” When listening to the Phoenician Dream recordings, Roberto recalled Rory referring to a specific passage of his violin playing as “‘very Prokofiev’, and [Sergio] Prokofiev is a famous Russian composer. So that means he knew not just his work.”

As our conversation with Roberto was drawing to a close, we felt we could have listened to him for another hour or two. One of the comments he shared with us has stuck out in our minds ever since, and had us reflecting on our own relationship with Rory’s music. When we picked up a Rory Gallagher record for the first time, we could have never predicted that we would come into contact with each other, form a friendship, and eventually create a blog, which has helped us not only on a personal level, but also with our professional careers. We never forced the fate of Rory into our lives; he naturally fell into it.

Somehow I felt that we were on the same wavelength … because I believe that somehow things happen magically in your life, you know? And [Rory] believed in the same way. You don’t force things to happen. If you are ready, things open and the connections are there also, it’s not you forcing them. And this philosophy of mine, it’s just been with me all my life. And I find it … was also Rory’s mentality; he had exactly the same thing. He believed it was magic, really … And when I see how my career went, somehow I can tell it’s all happening, I never forced anything, [like] meeting Rory. Some people would queue [to meet Rory], but for me it was just natural … I think he was a free spirit, so [we were] very similar.

Last week, we messaged Pete Lockett on his website, and to our delight (and astonishment), he replied to us in roughly an hour. Pete preferred to write a collection of memories about the collaboration for us to post, and so with his permission, we conclude our highlight on the Phoenician Dream recordings with Pete’s beautiful words:

Recollections – Recording and collaborating with Rory. Pete Lockett

I recall this recording very clearly. It was early in my career and to be in the situation to not only record with the great legend of Rory Gallagher but to also collaborate, improvise and compose with him as well. It was a massive honour. One always approaches such a situation with an air of caution. There is no way of knowing the personality type of the person you will be working with. There are some massive egos out there and getting caught in that steam is wholly unpleasant. Thankfully, Rory was the complete opposite. An absolute gentleman. Down to Earth, polite and to my amazement, not standing behind any ego whatsoever. Being so incredibly sensitive, one might even say he was a little vulnerable. In my humble opinion, artists who allow this degree of ‘feeling’ can really get into the emotionally creative side of music making in a much more intense and meaningful way.

The studio was one of those old Warner Chappell studios upstairs off the back of Oxford Street in London. A pretty unassuming small studio for such a personal collaboration. It was the perfect fit. We spent the day exploring a few different set ups and improvisational approaches and went with the flow. Rory was great at ‘allowing’ it to happen and let the music grow organically from the situation. Seeing how he thought and felt about the energy and music was incredibly inspiring and truly pulled out the best from Roberto and myself. Once his ‘sound’ kicked it was like being pulled into an infinite musical vortex. I honestly had never experienced anything like that before. Words are poor messengers in conveying exactly how that manifested. It was not long after this that Rory sadly passed away. It was devastating to realise that he was gone and that his apriori energy was only going to remain with us as recordings and audio.

I have been lucky to have worked with a lot of great performers over the years. Two really stand out for me are Rory and Steve Gadd. They both had that incredible degree of ‘purity’. In creating with them you become intensely aware of the ‘gravity’ they generated. They pulled you into their orbit in such an inspiring way that tuned in all your receptors and allowed your creative integrity to remain perfectly intact. It’s a rare thing indeed.

As always when we prepare a blog post, our first point of research is to check prior literature on Rory. Quite frankly, we as researchers, historians, and – most importantly – fans, find the lack of information and analysis regarding Rory’s session work from 1985 – 1995 appalling in past publications. If mentioned, then these sessions take on the format of a footnote at the back of the book, and in terms of documentaries, well, we might be lucky if there is a whisper of acknowledgement. At Rewriting Rory, we recount Rory’s career by not only balancing the narrative and filling in the blanks, but also striving to understand the cause of this misrepresentation, this (perhaps) unintentional damnatio memoriae, on the way in which the memory of the last ten years of his life was placed out of sight, and hence, out of mind.

We notice a pattern whenever reading about Rory, from the brief – though startling – comment in Colin Harper’s obituary in Mojo magazine (“Gallagher’s life was coming full circle”), to the question posed in Julian Vignoles’ Rory Gallagher: The Man Behind The Guitar (“Did Rory Gallagher really want to live on?”)

Rory’s life is portrayed within the predictable rise and fall, the potency of his youth to his creative barrenness of middle age. Journalists rely on the familiar interpretation of Rory’s withdrawal from the spotlight during his later life as a desire to withdraw from life forevermore. However, in our opinion, these are lazy explanations. If anything, as this post (and many more) uncover, Rory was broadening his musical horizons. Against all odds (from popularity decline, to worsening physical ailments), Rory was embarking on a new phase in his career, from forming a new band, to experimenting with styles. Roberto Manes mentioned in our conversation that he believes one of the many reasons Rory and him connected was because “[Rory] needed some fresh energy, and you could see all around me it was happening, because I had the band there, [and] new sounds.” And if we look at his final recordings, Rory appears to be searching for a new inspiration, this “fresh energy”, due to the fact he participated in a diverse range of music: new wave rock (Energy Orchard), country blues and bluegrass (Peter Green tribute), eastern and jazz (Roberto Manes and Pete Lockett), and raunchy blues (Eamonn McCormack).

So, we had to shake our heads as we read Colin Harper’s words “full circle”, because, to excuse our blasphemy, hell, Rory’s life was not even mid circle. As we reflect on our post for this month, we read of a musician progressing from his, if you will, blues to Cubist period, and in any other universe the stars would have lined up, but Rory’s body gave out before another destiny could take its course.

A section from our interview with Shu Tomioka, which we would like to share here, highlights the change in narrative we are hoping to achieve with our site:

In the early 90s, Rory was underrated in the rock world. When some magazines made special articles like ‘Great Blues Guitarist’ or ‘Great Fender Guitarists’, Rory’s name was often omitted. This made me so angry with it, and Rory was really hurt too. However, now people like you (Rewriting Rory) recognise him as one of the greatest guitarist of all time. I wish Rory would have known that still fans around the world love him.

On a final note, this article would not have been possible without the contributions from the following people: Joby Fox, Kevin Breslin, Shu Tomioka, Pete Lockett, and Roberto Manes. We are indebted to their kindness, willingness to help, and taking the time out of their schedules to chat with us.

Music of Peter Green, 1994. Photograph by Shu Tomioka

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply