The story of Rory Gallagher, the Irish blues-rock guitar virtuoso, needs rewriting.

Most accounts of his life depict it as a rise and fall: from a fresh-faced youngster taking the world by storm with the power trio Taste in the late 1960s to an overweight, passé man whose “best years” were behind him by the early 1990s. This simplistic and inaccurate narrative reduces Rory’s career to a before and after, with the 1987 album Defender (or even 1982’s Jinx!) frequently marked as the dividing line: between success and failure, innovation and irrelevance, healthiness and sickness…

This sort of drivel might be expected from the media, keen to oversensationalise in order to increase readership, but it is disheartening to see these types of comments regularly surface in Rory fan groups. Whenever the official Rory Gallagher Facebook page posts a photo of Rory from his later years, I find myself tensing up, anticipating the inevitable flood of disparaging remarks about him. Over the years, I’ve seen everything from “pathetic” and “let himself go” to “shadow of his former self” and even “I only like looking at him when he was young and beautiful.”

These so-called “fans” claim that Rory had lost his talent by the late 1980s and was no longer producing high-quality music. Yet, when I’ve confronted them, many admit that they aren’t really familiar with his later performances or haven’t given Defender or Fresh Evidence a fair listen, proving just how damaging hearsay can be. I defy anyone to put on Montreux ‘94 without being moved to tears by Rory’s incredible rendition of ‘I Could’ve Had Religion’ or witness his performance at the Temple Bar Blues Festival without being utterly awestruck by the way he pours his heart and soul into every note.

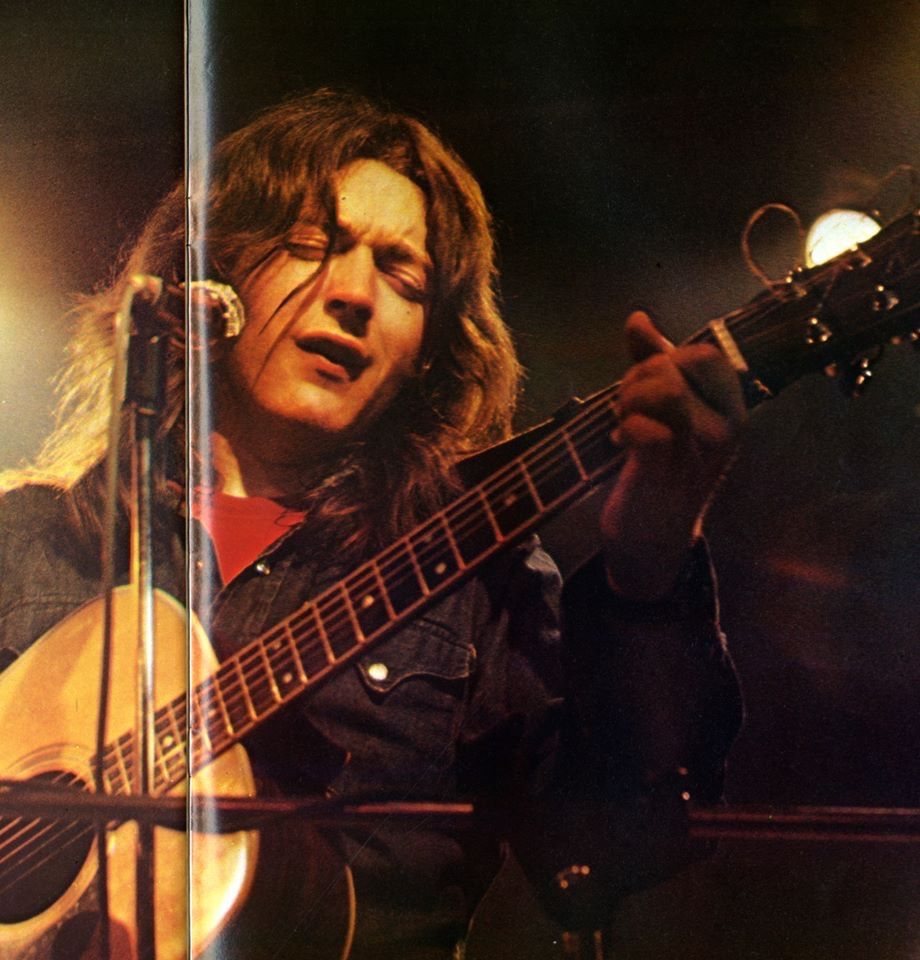

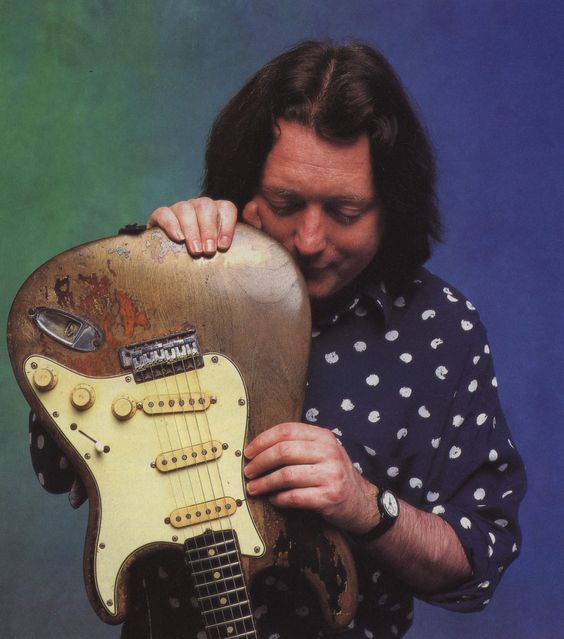

So, what are these assumptions based on? Well, largely on the fact that Rory struggled with increasing health problems in his final decade, which led to changes in his appearance, weight gain and an inability to move around the stage with the same energy as in his youth. For these people, Rory’s decline in health somehow equates to a decline in his musicianship, despite no evidence to support this. Even concert footage reflects fickle standards of society, with cameras that once frequently focused on Rory’s handsome face in the 1970s increasingly shifting their attention to just his hands and Stratocaster in his later performances.

You might be wondering by now what the fundamental problem is with all this. After all, it’s natural for fans to have preferences about different periods of Rory’s career. And you might be right in that regard. However, when it crosses into personal attacks on Rory or when people dismiss his later music based on misconceptions or unfounded assumptions, that’s when I feel compelled to speak up.

And that’s because I see these comments as showcasing an overwhelming lack of compassion and understanding for Rory, yes, as a musician, but even more so as a person. If I can perceive the man’s physical and mental anguish through a screen some forty years later, then it blows my mind that so many people alive at the time, who saw him in concert, who read his interviews in magazines, never stopped to think that something might have been wrong.

Although I suppose it is inevitable when the Rory Gallagher story to date has not done him justice. In biographies and articles, very seldom has his mental health been explicitly discussed, nor have the words “depression” or “anxiety” been openly stated. Instead, writers have skirted around the issue, describing him as overly “sensitive,” “melancholic” or burdened with a “sense of gloom” or “the weight of the world on his shoulders.” They almost scoff at the fact that he was a solitary person who found it difficult to form meaningful relationships with others.

Too often, writers are keen to attribute Rory’s challenges to eccentricity or abnormality, or label him with terms like autistic, asexual or alcoholic. This has been compounded by former bandmates, such as Gerry McAvoy, who dismissed Rory’s struggles in Riding Roughshod (Dónal’s words) and told Dan Muise in 2002 that he left Rory’s band because the guitarist had “lost the plot.” Now in 2021, a time when mental health is less taboo and more understood than it once was, it’s finally time to address the elephant in the room.

My aim with this unashamed rant is not to psychoanalyse Rory – I love him too much for that, and it’s not my place to do so, given that I never knew him personally. Instead, it’s to speak honestly as someone who has also faced their own mental health struggles, who recognises a kindred spirit in Rory and who wants to ensure that his story is portrayed with the balance and truth it deserves.

“What’s wrong with your brother?” (1950s-1960s)

In 1956, Rory moved to Cork with his mother Monica and younger brother Dónal. Dónal has often mentioned in interviews how Rory felt the pressure of being the older sibling and assumed a certain responsibility to look after his family in his father’s absence, even though he was just eight years old. Rory also worried about attending a new school – North Monastery Christian Brothers – especially as he would have to speak Irish, which was not necessary in Derry where the family had previously lived. To add to these anxieties, Rory feared that the notoriously strict Christian Brothers would discover his passion for playing guitar. And he wasn’t wrong to worry.

After performing Cliff Richard’s ‘Living Doll’ at a school talent contest, young Rory was severely reprimanded for playing what was considered “the devil’s music.” He ended up being suspended from school, along with Dónal who was seen as guilty by association simply for being his brother. According to Dónal, from that day forward, Rory became extremely reserved, spending more and more time alone and becoming unwilling to open up to others.

Unfortunately, the abuse from the Christian Brothers did not end there. In 1963, Rory and his showband made headlines in Cork after a riot erupted at one of their concerts, leading to an ambush by the crowd. Rory flung his body over his beloved Strat to protect it, resulting in him being beaten in the process. The incident badly shook him, and he spent three weeks off school due to the distress. When he returned, his mother wrote a sick note claiming that he had the flu, but the priests, having seen his photo in the newspaper, knew otherwise. As a result, they beat him even more severely. Rory suffered in silence, and it was only by chance that Dónal noticed the state of his legs one night when undressing for bed; they had become septic. Rory begged his brother not to tell their mother, but thankfully he did. Monica intervened, taking Rory to the hospital for treatment and then transferring him to the more liberal St Kieran’s College. However, the trauma of this event at such a young age stayed with him.

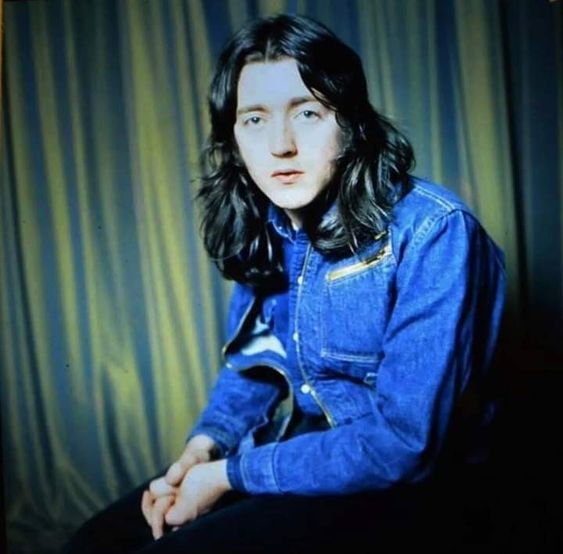

Reflecting on the days of Taste, bandmate John Wilson remarked that Rory spent twenty-two hours a day wanting to be the person he was for the two hours a day on stage and that he was “painfully shy” and had trouble communicating with others. During Taste’s tour with Blind Faith, Eric Clapton even asked Dónal directly: “what’s wrong with your brother?” There was nothing wrong with Rory; rather, these read as classic signs of a naturally shy and introverted person who simply feels self-conscious and insecure around others.

After the break-up of Taste and the ensuing negative press, Rory was unfairly portrayed by his former band members and the music press as a control freak and tyrant, despite it being their deceitful manager Eddie Kennedy who had spread lies and turned the three members against each other. This experience deeply wounded Rory, and he spent several months back in Cork, isolated in his mother’s house. According to Dónal, this was when he first became concerned about the “terrible depression” hidden within his brother and that it took a while for him to come back out of his shell. Even when Rory tenaciously re-emerged with his new band in 1971, the painful memories lingered throughout his life: he never played a Taste song again on stage and became increasingly guarded, only trusting Dónal and long-term friend and roadie Tom O’Driscoll with his affairs.

Throughout Rory’s career, he wrote many songs about Taste that, to an untrained ear, seem like classic break-up songs (‘I Fall Apart’, ‘For the Last Time’, ‘Bought and Sold’) and became very uncomfortable whenever the topic was broached in interviews. Nobody in Taste ever received any money for their music and legal battles persisted until 1992, with Rory spending almost 80% of his income on them. It’s unsurprising, then, that these experiences had such an enduring impact on his mental health.

The Golden Years? (1970s)

Looking at Rory’s smiling, confident face on stage throughout his successful years in the 1970s, it might be hard to imagine that he suffered from stage-fright. Rory’s transformation from backstage to front stage has often been described as “traumatic” and the Jekyll-Hyde paradox that he himself talks about in ‘Shadow Play’ is a familiar trope used by those who knew him to describe him. Leading up to a concert, Rory got extremely nervous and often did not eat until later in the evening. We catch glimpses of his nerves on film, such as backstage in Irish Tour ’74 where he paces the room wringing his hands before walking out on stage (also aggravated by the dangerous situation of playing in Belfast), in the Macroom ‘78 documentary where he accepts a Hot Press award and turns bright red and stammers, or in pretty much any interview situation over the years, where his voice wobbles and he strums nervously on his guitar. “Rory had an anxiety problem and always had,” harmonica player and close friend Mark Feltham later said in an interview with Colin Harper, while ex-sound engineer Phil McDonald described Rory as a “nervous fellow” who was “hesitant” and “not as confident as you’d imagine.” The mental strain of going out night after night to perform, give interviews, put himself in the public eye when suffering from anxiety and being so reserved is truly admirable.

By the late 1970s, Rory was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with his music and band. In 1977, he scrapped an entire album (what would become 1978’s Photo Finish) on the day it was to be presented to Chrysalis Records and then accidentally shut his thumb in a taxi cab, breaking it and putting him out of action for several weeks. The temporary inability to work added to Rory’s depression and, in moments alone with Monica and Dónal back in Cork, he would confess his worries about the direction his music was heading. This prompted him to change the line-up of his band and return to a three-piece format.

Around the same time, Rory started to develop a fear of flying after a particularly bad flight over Norway, where he feared that he was going to die. This was treated with anti-anxiety medication, but with the accumulated stress and pressure of his relentless work schedule (touring ten months a year on average), Rory began to rely on tranquillisers in his everyday life to help him deal with his anxiety. He worried particularly about his health, with band members noting how he would often take Paracetamol as a preventive measure for fear of getting a headache or if someone had a cold, he would be scared of catching it. Rory also struggled with insomnia, noting in an interview with Michael Kiely that he often lay awake at night worrying. For all his musical talent, he was plagued with self-doubts, constantly self-deprecating and never believing that he was good enough. Over the years, Rory mentioned many of his fears to journalists when asked, from claustrophobia, electrocution and flying to getting ill, hospitals and dying.

Torched? (early to mid-1980s)

Another blow to Rory’s self-esteem and morale came in the 1980s, a bad period for music where he was a “lone figure holding out against the march of pop glamour, the ever-present synthesizer and the decline of guitar rock,” as biographer Julian Vignoles has stated. During this time, the press started to make fun of Rory, calling his music old-fashioned and uncool and describing his check shirt as a gimmick. Things took a turn for the worse when Rory’s contract with Chrysalis finished and he spent three years without a record deal before forming his own label Capo. During this time, he also scrapped another album – Torch (which would later become Defender) – unable to achieve the desired sound he wanted. On a personal level, Jean-Noel Coghe notes that Dónal’s marriage in 1980 significantly impacted Rory, given their close relationship and his reliance on his brother. These feelings of loneliness and isolation were worsened by the death of his uncle Jimmy several years later, a man to whom he was very attached.

Rory’s hard-working attitude and refusal to slow down was also starting to take its toll and he had also developed a series of physical health problems for which he had to take steroids (although never officially stated, press reports from the period mention a thyroid disorder, psoriasis and asthma). Dónal also believes that Rory suffered a series of nervous breakdowns around this time, which were only apparent to him in hindsight. According to Dónal, Rory’s health anxiety led him to develop a somewhat blind faith in doctors, genuinely believing that they would help cure him. Rory would go out regularly for dinner with them and buy them paintings, unsure exactly of what he was being given and why and “naïve” to the fact that they were slowly poisoning him from the inside. Over time, his immune system became depleted from steroid use, making him highly susceptible to colds, flu and pneumonia. There is a terrible irony in this, given how staunchly opposed he was to all forms of drugs and cigarettes and had never so much as tried a spliff in his life.

Then, there were Rory’s superstitions. They had always been a part of his life – his mother read tea leaves and he followed horoscopes – but Marcus Connaughton states in his 2012 biography that these folk beliefs seemed to develop into, what some might consider, obsessive compulsive disorder at this point. Harpist Mark Feltham recalls Rory getting very upset when he only saw one magpie out of the bus window, while Gerry McAvoy recalls an incident where Rory got distressed after the bassist placed his shoes right to left on the floor. According to a 1990 Q article, Rory also increasingly struggled to walk into rooms with crooked paintings and worried about certain numbers. Rory himself acknowledged that it was “unhealthy mentally” and “dangerous to get that psychotic about it,” but that it was really “controlling [his] mind.”

“I’m not a quitter” (1987-1994)

It is often claimed that Rory’s depression emerged “suddenly” in the late 1980s. Rory himself said in an interview that he felt a strange feeling come over him during the recording of Defender and that he started to wear black because his check shirts had become like a “stigmata” to him. While things may have become visible on the surface from 1987 onwards, particularly in Rory’s changed appearance, there is a clear trajectory which shows how his problems had built up over time.

Biographers often point to the lyrics on 1990’s Fresh Evidence as revealing an insight into Rory’s psyche (“The darkness round your neck is like a metal claw”; “I feel suspended, got no lust for life”), but the signs were always there in earlier records, from ‘A Million Miles Away’ and ‘Edged in Blue’ to ‘Easy Come Easy Go’ and ‘I’ll Admit You’re Gone’, to name but a few. Rory may have been a man of few words and often had to be read telepathically, but you just have to listen to his lyrics to really get a sense of who he was.

Rory spent the last two and a half years of his life living at the Conrad Hotel in London. Increasingly reclusive, in July 1994, he started to experience suicidal thoughts. By sheer chance, Rory received a phonecall from his friend Rudi Gerlach as he was contemplating stepping out onto his window ledge; thankfully, Rudi managed to calm him down, although a transcript of a private conversation between the two during this time is very telling of Rory’s increasingly troubled state of mind:

I’ll play for the rest of my life, but there’s more to life than that, you know? I’m suffering a bit of damage […] I’ve had enough lawyers and ‘make your will out’ and ‘who’s gonna get this’. I’m a corpse now already. It’s too much. But I’m also grateful for what I have. The friends I know. But I’m a bit guilty. Being an Irish Catholic, I feel obliged to get the job done. […] I’m not a quitter, but I’m on the verge. I owe it to the people to keep going. I’m not a crybaby, but at the moment I’m a little bit of a crybaby. I must admit, I’m getting tired of a lot of things. […] It’s been a tough couple of years, Rudi, but I won’t cry on your shoulder. I’m not a quitter, but sometimes it gets too much. […] May the Lord allow me the talent, my nerves and health and things. I’m very precarious.

However, we don’t even need to dip into Rory’s private conversations to get a sense of just how bad he was feeling. His words in a 1993 interview with Guitar World truly cut deep:

To be truthful, I feel a bit used up after all these years. I’ve given so much of myself to this business that I really have difficulty getting enthused about anything. Often, I think that I’d be better off dropping everything and going fishing or back to my paintings. I don’t have a desire anymore to inspire sympathy in others or any other sentiment for that matter. When during many years no one has paid you the least attention, and to see some people in this business come back because it becomes the new trend, I can’t put up with that. It’s a fairly perverted attitude. You end up caring about nothing and you can only look at this circus with a distant and discouraged regard. For years, the ‘defenders of rock’ have in a way abandoned their responsibility, during the onset of punk and new wave, notably, whereas I continued to play and tour, to do the dirty work without the least bit of support, the least bit of publicity or coverage in the press. If today someone is interested in me in the least, I’m tempted to say stop by default. I have the chance to eat when I’m hungry and to be alive, but unfortunately that’s all that matters to me right now. Success, failure, honours or oblivion, none of that means anything to me.

Despite his increasingly poor mental state, Rory insisted on still performing. He gave a barnstorming performance at Montreux in 1994, yet locked himself away in his hotel room for three days after, convinced he had done terribly. Just a few months later, he was interviewed for the programme Rock ‘n’ the North and was described by the producer as “paranoid” and “anxious”, while in an interview for Swiss TV around the same time, he told interviewers that he was “happy as a musician” but “not happy as a person.”

Breaking the Stigma (1995 onwards)

A notorious perfectionist and workaholic, Rory continued to push himself right until the end. In January 1995, he undertook a tour of Holland, which was cut short due to illness. Following the tour, Rory isolated himself in his room at the Conrad Hotel. After much pressure from Dónal, two months later, he reluctantly agreed to be admitted to hospital, where doctors discovered that he had irreversible liver damage, caused by the long-term medication he had been taking (most of which is no longer on sale due to its link with liver disease). For many years, Rory had reported abdominal pains to his doctors, who prescribed him Paracetamol – a medication which exacerbates liver disease, especially if taken with alcohol – yet this was not picked up on until it was too late.

Shortly after his admission, Rory fell into a coma and Dónal was faced with the difficult decision to approve a liver transplant. Rory was recovering well and was due to be transferred to a convalescence home, but tragically, he contracted MRSA and died on June 14th at just 47 years of age. He had so much more to offer the world: there was talk of a collaboration with Bob Dylan, not to mention his own wishes to record an acoustic album, paint his own album cover and write a film soundtrack. It breaks my heart that he never managed to achieve this.

Too often, people hear the words “liver transplant” or see Rory’s weight gain and mistakenly assume he was an alcoholic. They often cite the ill-fated 1992 Town and Country Club gig in London where, after a reaction to his medication, Rory appeared drunk on stage. One bad night in a career spanning over thirty years and more than 2,000 performances. Cut him some slack. Other gigs from that same year, such as the Temple Bar Blues Festival (which features my favourite ever version of ‘Tattoo’d Lady’) show the incredibly high level at which he was still performing. Yes, Rory enjoyed a drink but, according to those close to him, he was never a heavy drinker, never drank to get him through a performance and, in fact, went through long periods of sobriety (Irish Independent, 26 June 2004). To misunderstand this part of Rory’s story is a true miscarriage of justice. While we can’t rewrite the past or Rory’s sad end, we can at least rewrite the present to correct misconceptions and ensure that his legacy is respected, untainted by misunderstandings about him.

Rory was quite simply an angel. A true gift from God. Not only was he almost superhuman in his talent, but also in his kindness, his humility, his grace. So, let’s take a moment to applaud Rory for his bravery, courage and resilience. To continue performing at such a high level for so many years, even as he was slowly falling apart on the inside, commands immense respect. Imagine being naturally shy and reserved, then adding depression and anxiety to the mix. Could you do it? I know I definitely couldn’t. And for this, I admire Rory so much. I’m so, so proud of him.

Rory is a huge role model when it comes to mental health, a powerful example of someone who had his fair share of demons yet kept persevering, kept going in the face of all challenges to achieve his goals. He’s taught me so much: he’s made me feel so much more comfortable in my own skin and given me the confidence to speak out about these important issues and my own problems in ways that I’ve never felt able to do before.

At the risk of sounding blasphemous, I describe finding Rory as a quasi-religious experience. Dónal himself has described Rory as “Christlike” in his purity, goodness and ability to turn the other cheek. I genuinely struggle to find any other way to explain his profound impact on my life without considering the possibility of a higher power being involved.

So, let’s stop ignoring Rory’s later years or viewing them as a sad coda in his life without taking the time to truly listen to his music, watch his performances and understand what he was going through. His talent did not wane at all at this stage of his career; if anything, it got better and better as he developed into a true bluesmaster. The world of rock often clings to notions of hypermasculinity, and many men find it difficult to accept or acknowledge this vulnerable side of Rory, but it’s time to break this stigma! Suffering from depression and anxiety isn’t a sign of weakness, it doesn’t diminish Rory as a man or as my hero, my inspiration, my guiding light.

Please let’s stop treating mental health as something taboo, let’s make it okay not to be okay and let’s ‘rewrite’ the story of Rory’s later years.

Leave a comment