Introduction: The Celtic King Without His Crown?

“I can’t go away and vanish like some people want […]

They’ll have to find a slot for me somewhere.”

Rory Gallagher, 1991[i]

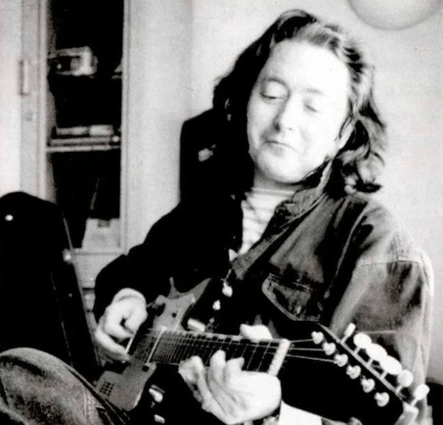

“What became of Rory Gallagher?” asked Françoise Rossi in her article on Gallagher’s return to Brittany in 1994.[ii] A decade had passed since Gallagher toured any of Brittany’s major cities, and his appearance at the annual Festival Interceltique de Lorient would be his first and final visit. Rossi summarises Gallagher’s ten-year absence with these noteworthy observations: “he has put on a lot of weight,” “he doesn’t seem to be particularly well,” “he hasn’t recorded for a long time,” “his bassist Gerry McAvoy is no longer at his side” and “[he] has remained loyal to his Canadian lumberjack shirts.” Reading over Rossi’s comments, we indeed repeat the question: what became of the man who was once described as the “fastest rising young star in Europe” following the debut of his band Taste (1966-1970)?[iii] An answer soon emerges when we acknowledge that Rory Gallagher’s career is typically framed within the hackneyed ‘rise and fall’ narrative, from a young man in the 1970s “with the world at his feet” to “fading [at] the margins” by the end of the 1980s.[iv]

The ‘rise’ in Gallagher’s narrative is shaped by a number of familiar accolades and performances that are, without question, astounding achievements in the initial stages of a professional musician’s life. Taste’s explosive presentation at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival left audiences anticipating the next step for this “best new group,”[v] while two years later, Gallagher—now a solo artist—“made Irish guitarists matter” when he topped 1972’s ‘Best Guitarist’ poll in the British magazine Melody Maker.[vi] As the Troubles hindered travel of international rock groups to Northern Ireland throughout the 1970s, Gallagher continued to tour the major cities, as demonstrated in the double album Irish Tour ‘74, with an accompanying film directed by Tony Palmer. This release in Gallagher’s catalogue is regarded as both a musical triumph (“Gallagher reaching a new height in his expression of blues”[vii]) and an important cultural moment in the Troubles by breaking “Belfast’s musical drought.”[viii]

Outside of touring, Gallagher occasionally participated in session work, his best known—and most highly regarded—contributions being The London Muddy Waters Sessions (1972) and Jerry Lee Lewis’s The Session: Recorded in London (1973). Another feat that is frequently featured in magazine articles (both then and now) is Gallagher’s jam with the Rolling Stones in January 1975, the chance at being a Stone sometimes earning more recognition than Gallagher’s own achievements. In 1976, Gallagher reached a “new peak” in his career, receiving critical acclaim for his album Calling Card. He would go on to further his “secure” reputation as “one of the most accomplished guitarists in rock” by headlining the Macroom ‘Mountain Dew’ Festival, both in 1977 and 1978.[ix]

Although 1977 was a “triumphant” year for Gallagher, biographer Julian Vignoles has suggested that it also marked “trouble” for the guitarist, acting as the precursor to the supposed ‘fall’ in his career narrative.[x] Vignoles highlights “a fork in the road” regarding Gallagher’s recording output, the release of Photo-Finish (1978) attained only after an abandoned album and change of band line-up.[xi] Gallagher’s “complex” and “satisfyingly interesting” blues style was now viewed in the music press as a “highly predictable” approach with “plenty of flash but very little genuine fire.”[xii] His media profile would further diminish over the course of the 1980s.

In Colin Harper’s 1995 obituary for Mojo magazine, Gallagher’s life was described as coming “full circle,” with 21st-century accounts reflecting this interpretation, as demonstrated by Vignoles and his question: “did Rory Gallagher really want to live on?”[xiii] Documentaries such as Ian Thuillier’s Ghost Blues: The Story of Rory Gallagher (2010) impede any chance of settling Gallagher’s ‘rise and fall’ narrative, particularly when many of the musical works and accomplishments from the latter half of his life are absent. After all, this is the story of Rory Gallagher, and yet Defender (1987) is breezed over in less than a minute and 1990’s Fresh Evidence receives no airtime at all. The documentary also does not delve into Gallagher’s live work in this era, aside from the portion of ‘I Could’ve Had Religion’ at the 1994 Festival Interceltique de Lorient, which is juxtaposed with anecdotes of how poorly Gallagher was, thereby inferring to viewers that his music was poorly at this time too.[xiv]

“It’s so hard to tell someone’s career in ninety minutes,” Gallagher’s nephew Daniel said at a Q&A for the first Panhellenic screening of Ghost Blues at the 2022 Gimme Shelter Film Festival in Athens, “But I think we did a very good job [in Ghost Blues] of giving an introduction to Rory.”[xv] We would tend to agree with this assessment if written biographies on Gallagher provided a comprehensive equivalent on the final decade of his career.[xvi] Instead, they tend to lean on the familiar ‘rise and fall’ narrative, interpreting Gallagher’s withdrawal from the spotlight as a desire to withdraw from life altogether.

If you enjoyed this ‘teaser’ extract from our introduction, then please consider purchasing Rory Gallagher: The Later Years, available now at Wymer.

[i] Stephen Roche, ‘King of the Blooze’, Seconds, no. 15 (1991), http://www.roryon.com/blooze412.html

[ii] Françoise Rossi, ‘Rory Gallagher marche au blues’, Ouest-France (10 July 1994), n.p.

[iii] ‘Sound Sandwich’, Hit Parader (March 1970), http://www.roryon.com/sound.html

[iv] Colin Harper, ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’, Mojo (October 1998), http://www.roryon.com/mojo.html

[v] ‘Sound Sandwich’.

[vi] Kenneth J. McKay, ‘Tar liom’, Strum and Bang (March 2020) https://medium.com/strum-and-bang/tar-liom-2423328b8c8d

[vii] Mark J. Prendergast, ‘Rory Gallagher, Taste, and the Blues Guitar’, Isle of Noises: Rock n Roll’s Roots in Ireland (1987), http://www.roryon.com/isle.html

[viii] Steve Carr, ‘The Night Rory Gallagher Broke Belfast’s Musical Drought’, Every Record Tells a Story (27 January 2017), https://everyrecordtellsastory.com/2017/01/27/the-night-rory-gallagher-broke-belfasts-musical-drought/

[ix] Both quotes from ‘Live Lines: Rory Gallagher for Macroom Festival’, Hot Press (9 June 1977), http://www.roryon.com/liveline374.html

[x] Julian Vignoles, Rory Gallagher: The Man Behind the Guitar (London: Collins, 2018), 153.

[xi] Ibid., 156.

[xii] ‘Rory Gallagher, ‘Irish Tour ‘74’, The Scene (August 1974), http://www.roryon.com/it304.html; Mike Boone, ‘Gallagher Has But No Fire’, The Gazette (16 November 1979), 73.

[xiii] Colin Harper, ‘Rory Gallagher (1948-1995)’, Mojo (August 1995), http://www.roryon.com/colin.html; Vignoles, Rory Gallagher, 258.

[xiv] The recently released Rory Gallagher: Calling Card documentary (The Rory Gallagher Story in the UK) fares much better in this regard. However, it is disappointing that the 52-minute version broadcast on Irish television— cut by six minutes to account for RTÉ’s advertisements—chose to remove segments on Defender and Gallagher’s songwriting abilities, which led to a gap in the narrative on his continued musical excellence in the 1980s.

[xv] ‘Gimme Shelter Film Festival Q&A’ (14 March 2022), https://vimeo.com/698242549

[xvi] See, for example, Jean-Noël Coghe, Rory Gallagher: A Biography (Cork: Mercier Press, 2001); Dan Muise, Gallagher, Marriott, Derringer & Trower (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002); Marcus Connaughton, Rory Gallagher: His Life and Times (London: Collins, 2012); Marcelo Gobello Chapurri, Rory Gallagher: El Último Héroe (New York: Lenoir, 2016); Fabio Rossi, Il bluesman bianco con la camicia a quadri (Genoa: Chinaski Edizioni, 2017), Vignoles, Rory Gallagher (2018).

Leave a comment