“Other kids were driving down the street in their Holden station wagon with their stereos blaring Led Zeppelin, [but] mine was “Follow Me”. That was my jam in my car.”

For the past week I have been thinking about Rory Gallagher’s solo on Mike Batt’s 1979 track “(Introduction) The Journey of a Fool”. To many Generation X Australians, this solo is nostalgia. It is the jingle to their favourite radio station. It is Triple, Triple, Triple Your Music. But to me it is a measure of time. At some point in 1979 Rory agreed to play on this track, not even a whisper of this from him in a magazine until the album hit the record shelves, did neither good nor bad, and now decades later I am listening to it, simply amazed.

Triple M was launched in August 1980 and, along with 2Day FM, was the first commercial FM radio station in Sydney. The station predominantly played hard rock, and set out to appeal to a blue-collar audience, contrasting to other stations around the country. Throughout the decades, the ‘Dr. Dan’ theme song for Triple M has been re-recorded by different guitarists. The first in 1980 by New Zealand-Australian guitarist Kevin Borich stays close to the 1979 original (fiery, sharp, and wailing), albeit without Rory’s string pulling / tremolo technique. For the 1990s, Australian guitarist Dieter Kleemann chose to reflect the end of the decade by incorporating heavy synthesisers, with his version released as a single on Mushroom Records in 1990. Finally, in celebration of Triple M’s 30th anniversary, American guitarist Slash was invited to put a 21st century alternate rock / West Coast L.A. feel to the tune. What was once a long-lost Rory Gallagher solo hidden between the grooves has now become a tradition of re-interpretation in Australian radio history. Although an iconic riff that has accompanied the Australian population for years, the question has to be asked: do Australians even know who Rory Gallagher is?!

According to Australian blues musician Gwyn Ashton, the answer is quite simple: NO. I had the great fortune to speak with Ashton over the phone one afternoon in September as he drove around South Australia to his next show. Late in the conversation, he shared with me this performance ritual:

Every gig I [play in Australia], I go, ‘here’s a Rory Gallagher song,’ and the place goes quiet. I say, ‘are there any Rory Gallagher fans in here?’ and not one person will put his hand up. And I’ll say something like ‘you people need an education’. These people need to hear his music.

From 2000–2005, Ashton played lead guitar for Band of Friends, headlining the first two Rory Gallagher Festivals in Ballyshannon during this time. Ashton spoke of another anecdote that involved the possibility of a Band of Friends in Australia featuring “Kevin Borich, myself, and Rory Gallagher’s rhythm section.” Unfortunately, when Ashton contacted music agents across Australia about this fantastic line-up, “nobody was interested” and the idea was never revisited. Hearing these stories from Ashton, I reflected on the pattern of Australian musicians falling onto deaf ears by the music business. But the picture got bigger when I considered the small appreciation we have shown for Rory’s connection to Australia, beginning with his first tour here.

In 1975, following a night out with his mates, John Spreckley was “immediately excited” when flicking through the newspaper and discovering an advertisement about a Rory Gallagher concert in Adelaide on February 6. Spreckley was a “huge fan” of Rory’s, though to his recollection, “we hadn’t heard anything about [Rory] touring [in Australia] before seeing that ad.” On the day of the concert, Spreckley and a few mates endured a train ride to the Festival Theatre on a sweltering summer day, and then hung out at the pub before the show. Rory was “wonderful and intoxicating” on the day, with “lots of slashing slide guitar” that “filled the Theatre.” Rory indeed lived up to his reputation for an outstanding show (“Rory and his band blew the roof off, and had everybody going crazy!”), but as Spreckley reminiscences, he mentions that, “I didn’t really notice at the time [but] the Theatre was probably only half full.” To Spreckley’s account, there was an interview where Rory addressed the moderate ticket sales. In his humble answer, apparently, “[Rory] wasn’t [disappointed] because people didn’t know his music, but once people know his music, more people will come to the concerts.” Rory’s 1975 show at the Hordern Pavilion in Sydney on February 8 saw a repeat of Adelaide, although in a disclosed interview with Australian writer and journalist Paul Dufficy, when asked about low attendance at the Sydney show, Rory brushed it off as an issue with advertising.

When Rory returned to Adelaide in June 1980, Spreckley made sure to get a ticket, and this time he was incredibly lucky, because unlike 1975, the Festival Theatre was now “sold out” for Rory Gallagher. Spreckley and his family managed to grab front row seats, remembering that, “Rory worked his heart out that night, and held nothing back.” In addition, this concert demonstrates Rory’s heart warming connection with a crowd: “At that time [Spreckley’s ex-wife] was pregnant with [their] son [and] Rory reached down and held [her] hands and looked at her as the show was coming to an end.”

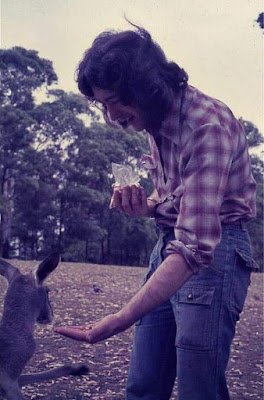

Photograph by Ross Buchanan

Australia in 1975 seemed to be a time when “people didn’t know [Rory Gallagher’s] music.” However, this is not to say that there wasn’t an effort to make Australians aware of who he was. Paul Dufficy became a Rory Gallagher fan during his final years at boarding school, remembering his first exposure to the Taste debut as “unbelievable.” As he recalls, “I hated being [at the boarding school] […] [and] Rory Gallagher’s music took me out of that place and made me think of things beyond that situation, so therefore I loved it.” If you would like to know more about Dufficy’s introduction to Rory, we encourage you to read it in his own words on the Stereo Stories site, or by clicking this link. When Lauren and I reached out to Dufficy several months ago, we were welcomed not only by his kindness, but also generosity, which included the passing down of some of his Rory memorabilia to us, such as newspaper clippings. A few pieces in his collection are his own work published in the 70s for Australian magazine publications. One such article (circa. 1975) opens with the current problem (“Rory Gallagher has had limited exposure in Australia”) and offers a solution to “fill this gap” by providing a summary of Rory’s career from Taste, as well as covering all albums, (“His latest ‘Irish Tour ‘74’ gives us Rory Gallagher in his most expressive environment, before a wildly enthusiastic crowd”). Five months after Rory’s tour of Australia, Dufficy wrote about the bootleg release In The Beginning, which features the perfect in-depth overview of Rory’s career for the casual music reader. A personal favourite from the collection is RAM’s 1978 “Requiem for R.G.B” (Rory Gallagher Band) following the announcement of Lou Martin and Rod De’ath leaving the group. Dufficy discusses the strengths of this line-up, referencing specific musical moments on records, as well as some reflections from his own memories of seeing Rory in Sydney, 1975 (“For we who saw him in Oz in Feb ’75, it was like standing in the eye of a cyclone”). Though (assumingly) Dufficy wrote these pieces as a fan first and journalist second, these examples contribute to the larger picture of presenting Rory to the Australian press and public sphere.

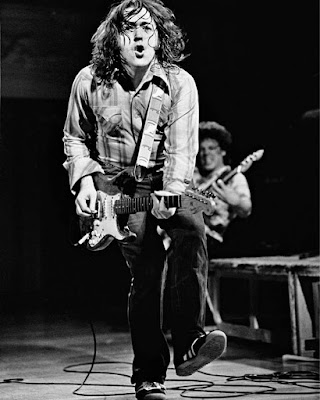

The music critics for the Sydney Morning Herald showed high hopes for Rory’s visit in 1975 (“it should be a good tour”), and Grant Thompson was a converted fan after a “few days” with Irish Tour ’74, hailing it as the “best tradition of rock and blues.” Rory’s character is portrayed in the Australian press with the usual adjectives of a “quiet, soft-spoken” Irishman that delivers a “dominating,” “fine, driving blues,” (Sydney Morning Herald, February 2 1975). In Rolling Stone Australia, Paul Comrie-Thomson praised Rory’s show at the Hordern Pavilion as “one of the finest showings of white blues guitar we have seen in Australia.” Comrie-Thomson describes in great detail the physical exertion of Rory’s performance (“he crouches coaxing the audience … in three seconds the slide has shot up ten frets … he has crashed an open chord resolution and spun around”), to crowd diversity (“Most of the people dancing were guys. Eastern suburbs surfs, North Shore denim overalls, Mediterranean’s, a couple of Chinese, sweating, everyone sweating”). Above all, Comrie-Thomson highlights Rory’s “total lack of pretension” (his “no flash clothes” or “no flash talk”) as the catalyst that “won” over the Australian audience. “Australians love a ‘battler’,” Donald Horne wrote in his 1964 book The Lucky Country, “an underdog who is fighting the top dog,” and as suggested by Comrie-Thomson, it is Rory’s ‘underdog’ quality that left the greatest impression on the Australian people and “made us all feel better.”

While in Australia, Rory managed to make a visit to the studios of the radio station Triple J in Sydney. Triple J started a month prior to Rory’s February 1975 tour, and was created under the Gough Whitlam government as a ‘National Youth Radio Network’. As former presenter Mark Colvin states, Triple J was “a voice of youth [when] there had been no real voice of youth heard before. There was a sense of rebellion, radicalism, [and] trying not to do what everybody else was doing.” The station took influence from overseas broadcasts, including live rock and pop performances, as well as playing primarily Australian popular music rather than international acts. Paul Dufficy remembers sitting in the car with a few friends at Central station when the broadcast came on, listening to Rory playing acoustic while “stoned and enjoying ourselves thoroughly,” before driving to the gig at the Hordern Pavilion. Afterwards, Dufficy and his friends drove up to Brisbane for the concert on February 11, this time scoring front row seats. Dufficy had this to say about the event:

I remember after [Rory] played “Goin’ To My Hometown,” I stuck my hand out as you do, and he came along and shook all these hands, and he shook my hand and he said ‘thanks for coming’. And I was just blown away, you know? [laughs]. So there you go. Very humble man.

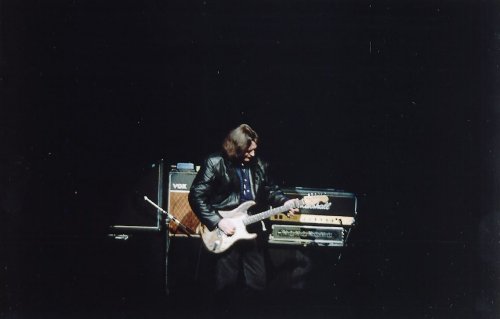

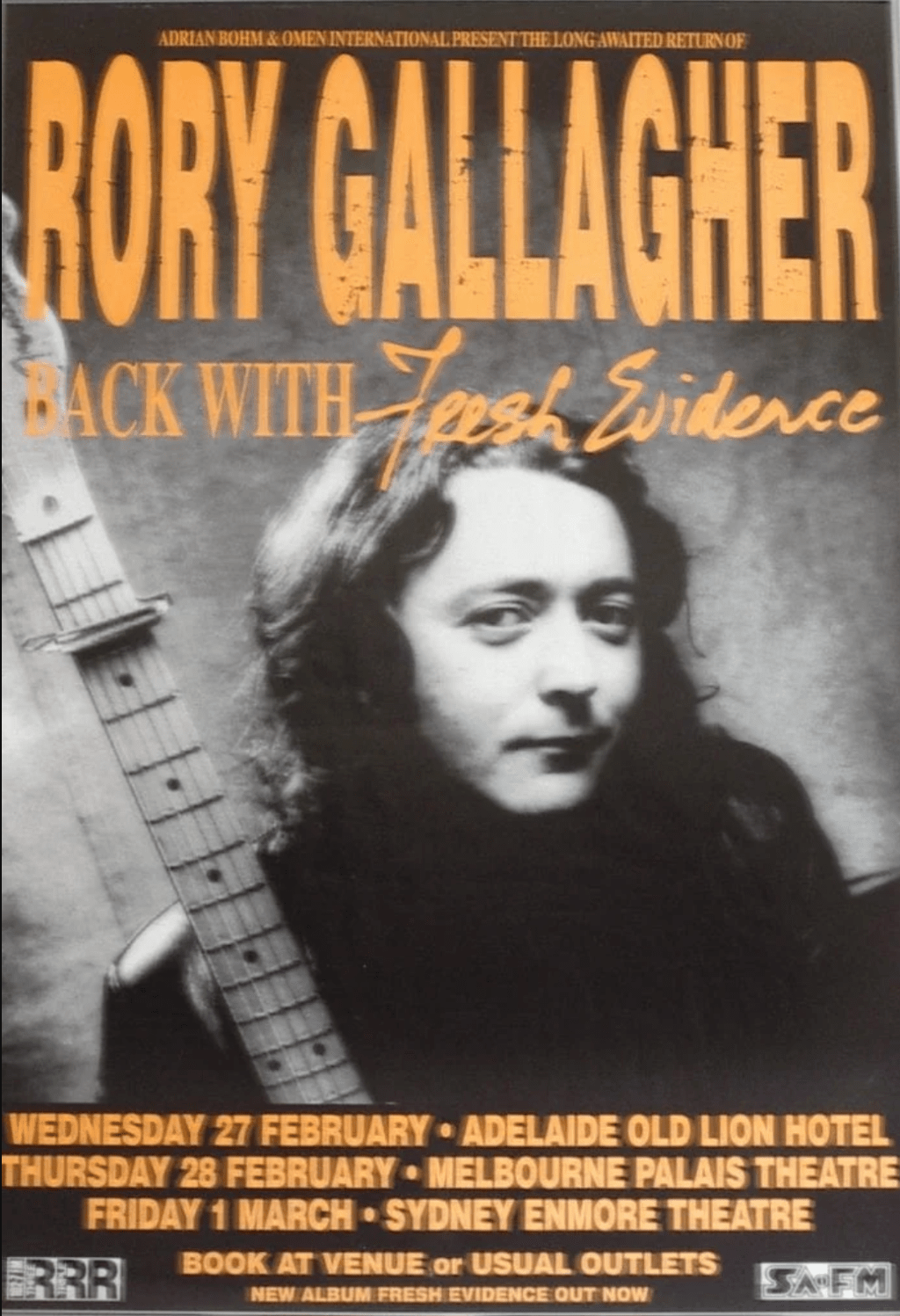

I have demonstrated in these few examples both Rory’s connection with the Australian people and integration into Australian popular culture and memory. My article will further explore this relationship with examples from fan testimony, archival research, and our own interviews. Neither the international press nor Australian press in the decades since Rory’s passing have tried (or cared) to acknowledge and document Rory’s ties with Oceania. Although my article primarily addresses Rory and Australia, effort has been made to include as much information we could find in the last six months of research about Rory’s 1975 and 1980 tours in New Zealand. Rory visited Australia in 1975, 1980, and 1991. According to local newspapers, there was a cancelled tour in 1976, and a visit to America was scheduled instead. There has been suggestion that Rory visited Australia in 1977, however, archival research does not support this. In addition to making a mark in our history, Rory’s 1980 Top Priority tour proved important in his recording history, with tracks recorded in Melbourne for his 1980 release Stage Struck, as well as photographs by Patrick Jones of Rory both backstage and in front of the Playroom on the Gold Coast used for the inner sleeve.

Rory’s dates in Australia on his 1980 Top Priority tour can be viewed as his most successful visit. As advertised in the Sydney Morning Herald, management was forced to add a show in Sydney at the Capitol Theatre for June 29, contrasting significantly to the “half full” attendance five years earlier. Kim Trengove described Melbourne’s Palais Theatre as “numb” and “reeling” following Rory’s “high-power” and “fiery” performance on June 24. Melburnians were so captivated by Rory, that they “demanded three encores from him, and Gallagher’s playing seemed to improve each time.” As a matter of fact, the entire continent seemed to be struck with a case of ‘Rory-fever’ in June of 1980, with the tour deemed “a success beyond expectation,” which lead Rory “to pledge a return in 1981.” Newspapers reported of the rise in radio play of Rory’s song “Philby”, despite being “completely ignored on original release” as a single earlier in the year. Besides a passage of time, what had changed for Australian’s to suddenly become Rory Gallagher fans? For a start, by this stage in history, Australia’s popular music landscape had significantly developed into its own brand of hard rock and punk, as an influx of bands defined the lives of Australian listeners, including Midnight Oil, Dragon, Cold Chisel, and Australian Crawl. This gritty, rock edge coincided with the hard rock style of Rory’s sound towards the late seventies and early eighties, appealing to this wide group of music listeners in Australia. Furthermore, if the first tour was tainted by advertising problems, then this issue appears to be resolved by the second tour. New Zealand artist Chris Grosz, known for his tour posters of blues acts such as Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder, designed the 1980 Top Priority tour posters for Oceania. Chris discovered Rory’s music through Taste, and particularly liked the “passion and unstoppable action-packed-attack” of Rory’s sound and soloing. At the time, Chris was working for Australian Concert Entertainment when he was approached to design the poster, tour program, and backstage passes. Chris revealed to us his creative process and what inspired him for this project:

I would listen to the artist’s albums before starting a design [and] get a visual feel for their artistry (musically and lyrically). This usually influenced the visual look and provided an idea for the design. In the case of Rory, I used the orange and the green to suggest some form of coming together during the Troubles […] [as well as to convey Rory’s] slash and burn style of Fender Strat playing.

If you are interested in learning more about Chris’ career and art, please visit his website by clicking this link.

‘Takes away the aches and pains’: Rory and the Australian Public

In the 2011 Census, approximately 1 in 3 Australians claimed to have Irish heritage. Since the transportation of Irish convicts in 1788, Australia and the Irish people have shared a long history. Unfortunately, this history has been tinged with class discrimination, racism, and religious segregation. As discussed in Mick Armstrong’s 2017 article, “anti-Irish racism” in Australia “was a direct product of British imperialism,” with Irish communities perceived as “lazy welfare cheats, drunken, dirty, uneducated, violent, criminal, stupid, [and] with hordes of kids.” The subhead in Trengrove’s review of Rory’s 1980 Melbourne concert claimed that, “Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher hit the Palais Theatre last night with more force than an IRA raid,” briefly reinforcing the connotation of the Irish as violent, particularly within the context of the Troubles. However, display of the hostile, anti-Irish attitude embedded in the Australian character was worse the following night when Rory was “abused” and called an “obnoxious little bastard” as he was ejected from the Wrest Point Casino in Hobart. Rory was deeply shaken by the event (even referring to it as “the most disgusting incident of my fifteen years on the road”), that he caught the next plane to Queensland ahead of schedule.

Although some factions of Australian society reflected prejudice, others found points of connection and solidarity with their Irish roots through Rory’s visit. Paul Patrick Martin recalls first seeing Rory on television in Ireland, where he performed “Blister on the Moon” with Taste. However, it was while Martin was living in Adelaide that he saw his musical idol in concert. Martin’s recollections of the Adelaide show in 1975 reflect the sentiments explored in the beginning of this article (“[Rory] was so humble and polite to the audience, and tore the roof off the place! His energy onstage could light up a city!”). After the show, Martin was fortunate enough to meet Rory, and this was what he shared with us about the occasion:

A mate of mine worked for Festival Records, who distributed Rory’s label, Chrysalis in Australia. He picked Rory and the band up at the airport and drove them to the gig. I saw him in the foyer at interval (his band did the support slot), and he invited me to a wine bar where he was taking Rory for a drink after the show. I didn’t have to be asked twice! Rory spotted the t-shirt I was wearing, with a Celtic harp and the Irish Gaelic greeting “Cead Mile Failte” (a hundred thousand welcomes) on it, and he walked over and said the greeting and asked me where I was from! I was blown away that he came over to talk to me, no big star bullshit! He asked my name, how long had I been here, and [we had] a general chat.

Years later, Martin and his wife saw Rory’s “fantastic gig” at the Old Lion Ballroom in Adelaide during his 1991 tour.

When [the band] had finished, I gave a bouncer a piece of paper with “Cead Mile Failte a Ruari” on it, and asked him to please give it to Rory. He came back and said “I don’t know what you wrote mate, but he wants to see you”. We went backstage to the dressing room, I shook hands with Rory and said that he might not remember me from our previous meeting, but he said, “I do, yeah”. I introduced my partner, and then told him that I had named my son after him. His reaction was very gracious, he said, “ah, that’s lovely”, and actually looked a bit embarrassed! He then told me that they had just arrived at the airport, checked in to their hotel without any time to relax first, and that all he wanted to do was to stand under a nice hot shower. I thanked him for seeing me and wished him well.

To the present day, Martin cherishes his memories of Rory as a “very lovely, humble gentleman,” demonstrating Rory’s impact on the Irish-Australian community on both a personal and musical level (“He inspires me to do my best when I perform”). Coincidentally, on the last night of his 1991 tour, Rory bumped into a few musicians from home hours before his flight from Sydney to the United States. Fiachna Ó Braonáin, guitarist and vocalist for the Irish group Hothouse Flowers, remembers having a chat with Rory at Sydney’s Sebel Townhouse Hotel bar, describing the experience as “like meeting a hero.” “Rory was nervously preparing for a long haul flight,” Braonáin told us of the short exchange, “and Hothouse Flowers had just arrived into town to kick off an Australian tour. So we sat and shot the breeze about music and touring and what a wonderful way of life it was.” As Braonáin looks back on the moment, he recognises the privilege of sharing “the company [with] a kind, gracious, and generous human being” – a feeling that has stayed with him ever since.

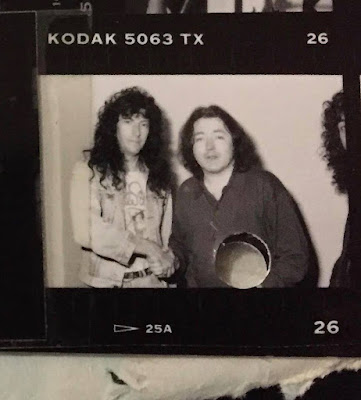

Photograph by Tom Byrnes

‘Teenage salvation on a twelve inch disc’: Rory and New Zealand

Graeme Downes, founding member of the Dunedin punk band The Verlaines, explained in a 2005 article for Stylus magazine the musical landscape in twentieth century New Zealand. “In Dunedin we were extremely isolated,” Downes wrote in an email to journalist Dave McGonigle, “and it took a long time for musical trends to filter down this far.” Downes described how a record from the United Kingdom could take up to “two years” to make its way to the pressing plants in Wellington, using the example of Joy Division: “Ian Curtis was dead and buried before any JD records were released here.” We discovered that Rory Gallagher fans in New Zealand made similar statements. Peter Garrett was introduced to Rory though the Irish Tour 74’ LP, and described discovering his music as a “privilege” due to his unpopularity in New Zealand. “Rory’s music was a huge part of my life in my teenage years and still is,” Garrett wrote to us, and although Rory never made it back to New Zealand during his final tour of Oceania in 1991, Garrett and his friends flew to Sydney for the concert at the Enmore Theatre. Garrett remembers how the packed theatre turned into “mayhem” as everyone “leapt out of their seats and ran to the front of the stage” as soon Rory played the first note. The concert was a “dream come true” for Garrett and his friends, in part because “we had never found a cover band in New Zealand that did Rory songs, [and] so it was unreal that the first time we hears them live was from the man himself.” Thirty years on, Rory’s performance at the Enmore Theatre is an experience Garrett and his friends talk about.

Greg Cotmore grew up in Wellington listening to the local pop radio station Wellington 2ZM, which provided the greatest “escape, hope, [and] joy” to the life of a teenager in New Zealand suburbia. 2ZM began in 1937, and during the 1970s played a rotation of Hot 100 singles from the UK, America, Australia, and New Zealand. On the weekends, DJs often played both sides of a record, and on one Sunday evening in 1972, Cotmore first heard Rory’s Live! In Europe, and was immediately “hooked.”

It was raw, it was relentless, [and] it was real. This was no wham bam glam pop shite—this was a blast of white-hot intensity. Teenage salvation on a 12-inch disc. I saved-up my pocket and paper round money and bought the album. My mum and dad’s home hi-fi never knew what hit it. I would sit gaping at the album cover, focused on the battered sunburst Fender Stratocaster, and imagining myself at the concert.

Fantasy became reality in 1975 when Cotmore won tickets from 2ZM to attend Rory’s Wellington concert. The radio station also gave away a signed copy of Rory’s 1973 album Tattoo, which Cotmore “cherishes” to this day. According to Cotmore, Rory’s playing was “mesmeric,” and the entire performance “explosive,” that listening to tracks such as “Cradle Rock” and “Tattoo’d Lady” cause a “searing chill up [his] spine” as memories flood back from the show in Wellington. In some cases, a live show was the gateway into becoming a Rory fan, like what happened to Stephen Kilroy in 1980. Kilroy was learning to play guitar when a friend suggested that he go see Rory at the Regent Theatre in Dunedin on July 4th. Kilroy remembers that before the show started, Rory announced that the support act failed to show up, and therefore he played for three hours with a break in-between to make it worth the crowd’s time and money. By the end of the three hours, Kilroy had been “converted” to a Rory fan, and his lasting impression was of a man that “could play [with] no pretensions, [but for] the joy of music, [which] seemed to come from him so effortlessly.” On this note, through our research, we found many connections with Rory and Australian musicians, and we were quite alarmed by the lack of recognition this impact (both personal and professional) has had in the Australian press and music history. We aim to fill in this gap for the final section.

‘It was like an epiphany’: Broderick Smith, Ron Smeeton, Dave Hole, Jeff Lang, Marc Lee De Hugar, Gwyn Ashton, & Rory

It’s easy to be struck by the presence of Rory’s shadow in Gwyn Ashton’s musical career and life. Ashton first became aware of Rory as a teenager in the seventies and at this stage in his life he was already a music fanatic (“like a sponge,”) absorbing “twenty years of music in about two years,” from the British blues boom, to the California sound, and the fifties rock n rollers. Ashton was introduced to Rory’s music by a fan in his neighbourhood, who had often heard Ashton and his band rehearse. As a starting point, Ashton was given three albums: Live! In Europe, Irish Tour ’74, and Calling Card. “That night I listened to them, and it was like an epiphany,” Ashton told me over the phone in our interview, “I thought, ‘wow, why haven’t I heard this before?’ It was probably the best guitar playing I’d heard, and the songs were really good as well.” Rory’s impression was so immense that it caused Ashton to take a three-month break from his band in order to “study Rory,” spending endless hours rewinding the needle on his records to decipher the guitar work. Although other bands such as ZZ Top and Budgie were also in the rotation on Ashton’s turntable, it was Rory that was “on top of all the other ones,” partly due to the predominantly blues foundation of Rory’s music.

In 1980, Ashton had the chance to switch the records for a seat in the Festival Theatre when Rory played in Adelaide, remembering it as a “blinding show.” The concert was important to Ashton for many reasons: foremost, as a fan (“I hadn’t seen him before, I hadn’t seen videos, [and] I had no idea what he looked like apart from the album covers”), and secondly, as an inspiration (“I took all of what I’d seen and adapted it to how I played, and sort of added it to my textbook of guitar licks”). “I always thought if you learn too much of another guitar player you start copying them,” Ashton advised, and instead approached a solo with the thought: ‘what would Rory play here?’ Luck was certainly on his side on that Adelaide night, as Ashton had purchased tickets for the concert at the last minute. “The only ticket to get was right at the back, and I’ve been to concerts before and right up the back of the room is not a fun place to be.” Nevertheless, “Rory was on fire that night and it was so good that the energy even hit the back of the room, and that’s really unusual for any gig. You’ve normally got to be right down the front.” Seeing Rory live only intensified Ashton’s passion for the Irishman’s music, and now he was permanently “hooked.”

In 1991, after “begging the promoter” to let his band do the show, Ashton found himself moved from an offstage observer to instead on the stage as the support act for Rory’s performance in Adelaide. The opportunity deeply impacted Ashton, both as a “fan of Rory [and] as a musician and a peer,” and has resonated with him differently in retrospect, partially because of his time with Band of Friends, which “was totally unexpected.” The timeline of Rory’s entanglement in Ashton’s life, from “discovering the music to seeing Rory, then doing a gig with him, and [then] I’m in the band,” has played a significant role “as far as the stepping stones in music go” in Ashton’s career. Before the gig even started, Ashton experienced his first taste of Rory history when he struck up conversation with Tom O’Driscoll at sound check, and was offered the chance to play Rory’s 1961 Fender Stratocaster (“I said I’d love to”). Ashton has fond recollections of chatting with Rory backstage, noting how “quiet” and “quite shy” he was, and that although “he didn’t look particularly healthy” at this stage in his life, Rory’s set was “brilliant” that night at the Old Lion Hotel. Rory’s stage gear for the show had been supplied by Adelaide’s Derringers, and the next day Ashton and his band happened to rehearse with the same gear, with Ashton playing through the same amp Rory had. “I didn’t touch a single knob. I just wanted his sound, [and] to tap into a little bit of his psyche.”

Perhaps some of Rory’s “psyche” did indeed stay with Ashton as his career progressed, beginning in 1996 when he left Australia for England. During a quick stop in America, he managed to get Gerry McAvoy’s phone number, which eventually led to him joining Band of Friends in 2000. Ashton replaced both Brian Robertson and Robbie McIntosh in the band, the reality soon hitting him: “I had to replace not only Rory in this band, but I also had to replace these two hot shot guitar players. I thought, ‘I better pull my socks up here and do something right’ [laughs]. Prior to joining Band of Friends, McAvoy and Brendan O’Neill played on Ashton’s 1999 release Fang It! (which featured a cover of Rory’s “Who’s That Comin’?”). To coincide with its release, Ashton was featured in the Rory fanzine Stagestruck, created by Dino McGartland. In the early 2000s, Ashton collaborated with Lou Martin as a short-lived duo, performing a few times across England, and speaking fondly of the musician that he “learnt a lot off.” Ashton also befriended the late Ted McKenna, the two collaborating on Ashton’s 2007 release Prohibition(the album included another Rory cover, “Secret Agent”). Concert footage of Ashton, McKenna, and bassist Chris Glen from 2006 in Glasgow can also be found online. Ashton’s position in the preservation of Rory’s legacy and music continues to the present day. To celebrate what would have been Rory’s 73rd birthday, the estate uploaded a video of Ashton’s ‘Pickin’ on Rory,’ which included renditions of Rory songs, as well as Ashton originals. These recordings are in the current process of being remixed for a studio release in the near future. In addition, Ashton has recently promoted upcoming dates for a UK tour next year, featuring a spot on the 2023 line-up for the Rory Gallagher Festival UK in Nantwich. As with all musical guests that feature in this article, we direct our readers to Ashton’s website for further information about his career and music.

Photograph by Starman Brooks

Following two years of service in the Australian Army, English-born multi-instrumentalist Broderick Smith began his career in music singing and playing harmonica in the blues and boogie band Carson. From 1973 – 1978, Smith was involved in The Dingoes, which blended blues with Australian bush country music. The Dingoes are known for their hit singles “Way Out West” (1973) and “Boy on the Run” (1973). While on his first tour of Australia, Rory first met The Dingoes following his concert in Adelaide. “[Rory] turned up with a promoter we knew and asked if he could jam,” Smith shared with us via an email exchange back in March, “Naturally he played very well, and was a quiet guy as I recall. [He] complimented us, and was very nice.” This relationship continued when The Dingoes left Australia to work in America in 1976, coincidentally meeting in the His Masters Wheels studios in San Francisco as Rory was recording his new album (which would eventually be re-recorded and released as Photo-Finish). Rory jammed with The Dingoes once again, and Smith revealed that he was invited by Rory to tour Ireland playing harmonica for him and his band, but due to commitments with The Dingoes, Smith had to pass on the offer. After the split of The Dingoes, Smith formed Broderick Smith’s Big Combo, and was the opening act for Rory in Melbourne on his 1980 tour. Although Smith and Rory met on only a few occasions across the decades, the impact of Rory as a musical peer and acquaintance nevertheless stayed with Smith, as he ended his statement with these words: “I connected with [Rory] very easily, and over the years I have thought back to his demise in a sad, poignant way. Some musicians you meet over the years you tend to bond with, and he was one of them for me.” Following his visit to Japan, Rory’s first tour of Australia had a problematic start in Perth on February 4, 1975. This week we reached out to Australian slide guitarist Dave Hole, who had this to share about the incident:

The band’s gear didn’t arrive on the flight from Japan, so I received a call from Dónal to see if I could help rustle up some gear – in particular a Strat that was similar enough to his own for Rory to feel comfortable playing. I had a Strat but it was heavily customised for my own style of slide playing so I phoned around and we ended up with several for him to try out at sound check. He picked the most comfortable one and the show went ahead and was very successful […] [Rory] invited me back to the hotel (The Sheraton) after the show to hang out. He really was the most down to earth and genuinely modest guy.

At the Perth show, guitarist for the support act Bitch, Ron Smeeton, fondly remembers meeting Rory backstage, in particular his “quietly spoken” manner and “soft handshake.” Smeeton was aware of Rory’s music through Taste, and shared the same influences, such as the Delta and Chicago blues artists.

In addition to forming connections with Australian musicians, Rory also expressed encouragement to new blues talent, as demonstrated in our exchange with Australian singer-songwriter Jeff Lang. His style of roots-orientated rock, blues, and folk has attracted attention with the critics and the music community alike, as journalist Michael Bailey wrote in a review of Lang’s third LP Cedar Groovein 1998: “In an era where no guitar Gods have emerged, Lang finds himself the king of the six-string from Down Under.” During our research, we enjoyed familiarising ourselves with Lang’s extensive catalogue, as well as discovering a very humble and salt of the earth character in online interviews (find more at his website or YouTube). Lang met Rory as the support act for his Melbourne and Sydney shows on his 1991 Australia tour:

I didn’t get to hear Rory’s set in Melbourne as my band and I had to drive overnight in order to made the next night’s show in Sydney. But I watched the entire Sydney show. I loved his guitar sound on electric. He didn’t get the same Stratocaster sound that every second electric player was aping at the time from Stevie Ray Vaughn. His sound was his own, a purring, buttery, touch sensitive sound that could really sting the notes. The brief acoustic portion of his set was the thing I really dug […] He just played into a microphone in these fairly large venues, right in the middle of a raucous electric gig. Took it right down in dynamics.

Lang highlighted Rory’s practice of weaving “traditional Irish music into his blues-rock music” as an influence on his own song craft, as well as the “intensity” of Rory’s performances, “which was something to witness.” Similar to Smith’s remarks, Lang confirms that Rory was “complimentary” of his playing, adding that it was “kind of him, as I was pretty young and just finding my way with my music.” This friendly bond between Rory and young Australian musicians extended beyond the blues world, but also into the glam rock scene, as Candy Harlots guitarist Marc Lee Dé Hugar reminisced on The Australian Rock Show in 2021: “I got to know [Rory] really well, which was great. On his Enmore Theatre show [in Sydney], I was invited for a backstage thing, and next thing you know we just fucking hooked it […] They let us use the studio, and he told me how to wire pick-ups [and] it was like [being with] my grandpa or my dad, you know?” Despite the session being short, Hugar claimed that Rory and he “bonded.”

‘Are there any Rory Gallagher fans here?’: Building on Rory’s legacy in Australia

Since becoming a fan two years ago, Rory’s presence in my life has metamorphosed from a CD spinning through the machine, to making international friendships, expanding my musical tastes, and co-creating and writing this blog. To use Ashton’s phrasing, I wonder how this experience will impact the “stepping stones” in my journey, my career, and my input in Rory’s written legacy, particularly as I finish my final semester at university. In this example alone, we can see that Rory crosses over to a twenty-first century audience, staying relevant to a generation that has grown up far differently than his. As I come to the conclusion of this article, I return to the question posed at the start: do Australian’s even know who Rory Gallagher is? The answer: perhaps not.

Although his visits were infrequent and often brief, it is clear that Rory made an impact on the Australian public, even if unremembered. Rory’s legacy here has ridden the tidal wave, shifting from the unknown, to the known, and back to unknown. But if the case of ‘Rory fever’ in 1980s Australia has been cured, then how do we get another outbreak? Fans hold a candle to their hero through international Rory Gallagher tribute bands and festivals (Germany, Ireland, Japan, Italy, France, UK), but when it comes to Australia, the wick has extinguished, and we fail to see our appreciation for a musical figure that was the soundtrack (even the radio jingle) to many in this country. As stated previously, Rory’s visits to Australia and New Zealand have gone ignored in the international and Australian press, biographies, and documentaries. This article contributes to the long-overdue exploration of Rory’s connection to Oceania, and can hopefully initiate a rise in those Australians reading to pick up their Rory albums and catch that Rory fever again. While I have included only a small percentage of examples, I conclude this article with the goal of starting a conversation between fans of Rory Gallagher in Australia, encouraging them to reach out to this site, share their stories, and hopefully the process of documenting these experiences can begin.

Photograph by Tom Byrnes

We thank the following people for their contributions: Gwyn Ashton, Jeff Lang, Dave Hole, Broderick Smith, Ron Smeeton, Paul Dufficy, Paul Patrick Martin, John Spreckley, Greg Cotmore, Stephen Kilroy, Peter Garrett, Trevor Coppock, Chris Grosz.

Part 3 will be posted next month, and explores Rory’s final tour of America across the month of March in 1991.

Thank you for reading!

Leave a comment