RORY GALLAGHER – DEFENDER OF THE FAITH

For a while, we’d forgotten about Rory Gallagher: no albums in 4 years, no record company, some sort of mental block. We weren’t counting on the incredible vitality of this little plump Irishman who landed at the right time to tell us once again, with a few well-placed solos, the famous and smoky history of rock.

Years have passed since the world of rock, now a true suburban microcosm, discovered Rory Gallagher, the supercharged Irishman, at the Isle of Wight Festival where his energetic blues stopped the hippies in their tracks.

The world has changed. The universe of rock has mutated into a refreshing microcosm, a vehicle of prefabricated, even tendentious ideas. However, Rory Gallagher is always faithful: faithful to his roots, to his urgent and pressurised rock and roll, still loyal to his fans of yesteryear, still loyal to his western shirts, his jean jacket and his good old Stratocaster which has witnessed all sorts of things.

Rory was in Paris last month and he delivered to us pell-mell his memories, his plans and his reflections on his place in the 4th generation, even 5th generation, of the world of rock.

We all thought that Rory Gallagher had disappeared: no new album since 1982, no concerts apart from a short appearance at the Mont-de-Marsan festival last year and, even worse, no record company. What have you been up to recently?

The fact that I don’t have any record company currently is because I wanted to. My contract with Chrysalis required me to produce six albums. After Jinx came out, the contract came to an end, and through a common agreement between me and Chrysalis, we decided not to renew it.

With the emergence of new wave, synthesisers, new pop music, mohawks and sequins of all sorts of colours, I felt that I no longer fit well with the tastes of the general public and as I didn’t want to change my music at all, I thought that staying for a while outside of all that business wouldn’t be a bad thing.

In 1984, I went on the road again. I did two American tours in 1984 and 1985. We did some festival appearances. We even played in Yugoslavia.

So, it would seem that a new album is on the horizon?

The album is ready. Everything has been recorded, mixed. The sleeve is done. All that’s left to do is press the disc. For that, we’re looking for a record company that is ready to support the music that I play. It’s very hard currently because all the companies are looking for hits. It’s been a few months since everything’s been ready, but we’re having no luck. It takes time to get back on your feet. I don’t think that the album will come out before October 1986.

Can you tell us a bit about your new album?

It’s called Torch, you know like the Olympic torch that athletes pass from hand to hand from Olympia until it reaches the host country. It’s a symbol of light and continuity. Musically, it will be in the great Gallagher tradition of albums. I mean, a mixture of pure rock and roll, blues, rhythm and blues and part acoustic. We have recorded more than 20 tracks, and I have kept 10 for the album. However, because of all this delay, I have recorded some others too, so I might go back and revisit my initial choices.

Which musicians are playing on the album with you?

As usual, there’s Gerry McAvoy on bass and Brendan O’Neill on drums, as well as Lou Martin on keyboards for one track and another keyboardist, John Cook, on a few other tracks too. He accompanied us on our two US tours. Let’s say that the definitive formation remains the basic trio of Gerry McAvoy, Brendan O’Neill and me. The other musicians only appear when necessary.

In which style is the music on this album situated?

I think that Torch, in terms of inspiration, is most similar to Tattoo. In terms of sound and production, it’s closer to Against the Grain. All of this is approximate, of course, because the songs are new and the inspiration is new.

You have been in the music industry for 20 years now. You have seen the world of rock, hard rock and blues evolve and, above all, you have followed the development of new technology. Talk to us about your first recordings.

It’s incredible how much technology has evolved. In 10 years, we have gone from the stone age to post-industrial society. Just yesterday, we were recording in 4 track, whereas today, they’ll likely force you to record in 48 track. A good 24 track is more than enough for me. 15 years ago, I recorded Deice, my second solo album, in an 8-track studio. For me, it was one of the peaks of modern technology. Today, I think that I would like to remix that album because it’s one of my favourites.

At the time, we found this studio which was in East London, very close to the black ghettos. In fact, this studio was a reggae studio with absolutely incredible work conditions. Just next to the recording studio, there was a bingo hall. You just had to open the door and you fell into the slot machine bar.

Actually, we couldn’t use special effects like delay, echo or reverb, except for after 6am and before midday because that was the only silent moments. The room was very badly soundproofed. We had to do it very quickly, especially since we didn’t have much money. See, we did it anyway without worrying about the work conditions. I just wanted to play my rock at all costs.

Do you not think, to a certain extent, that Deuce synthesises in one album all the music that you have done throughout the course of your following albums, whether Tattoo, the blues album par excellence, Photo Finish, much harder than the rest, or even Against the Grain, which is very rock and roll?

Perhaps, yes, if you look at my career retrospectively. Deuce was the album of a kid who put all his passion into music. I wanted to make a harder album than the previous one, while still retaining my style at the time. I had just left Taste. There was still the furious madness of rock and roll, the Isle of Wight, the tour buses, a sort of speed. That album was done in 10 days, can you believe, no overdubs, no tricks, completely authentic and nearly all the songs were recorded in one take, which might make each title particularly seem like a base for what I did later. I like that album because it marked a huge turning point in my career and in my life. It has everything I love in it, even if it might have aged a bit with time: blues in its raw state with I Should’ve Learnt My Lesson, Irish folk like I’m Not Awake Yet and then more violent rock like Used to Be, which is my favourite song, and Crest of a Wave.

As you just mentioned it, you performed at the Isle of Wight festival with Taste in 1970. What does it mean to you to still be here today when the majority of artists from that era have disappeared?

It feels quite strange for me. As if I myself had missed the great moments of this era, when I was right in the thick of it. What I mean by that is everything has happened too quickly, perhaps too quickly, so quickly that I have never had the time to reflect on my career and to analyse what I’ve done. In fact, from 1968 to 1971, I was under a lot of pressure so only found out what was happening on an ad hoc basis. One day, I was in London, the next in Germany, then in the United States, just to come back immediately for the Isle of Wight festival. Perhaps that’s what has changed today. Everything is centralised, planned, calculated precisely. 15 years ago, we lived day by day and you to be wild to be able to survive.

But today, I feel like everything that I experienced in that period is a sort of dream for me. One day, I put together a group, we recorded an album and we found ourselves in the middle of a storm, a sort of cultural revolution, of which one of the engines was the excitement of youth thanks to rock and roll and which I followed.

Talk to us about the Taste era.

Taste was formed in 1965 in Cork in the south of Ireland. I had met a drummer, Eric Kitteringham, and a bassist, whose name I forget, in a pub. As we all liked rock and roll and blues, we decided to put together a proper professional group: and so Taste Mark 1 was born. We toured for almost two years, at our own cost, without a record company contact, and we did all the pubs, from Hamburg to Belfast passing through Glasgow. After two years, the experience not being particularly convincing, my musicians left and I found myself alone.

In fact, the true history of Taste starts from that moment where I found true blues musicians – Richard McCracken on bass and John Wilson on drums. With this line-up, the last by the way, of Taste, we recorded two true studio albums Taste and On the Boards and two live albums Live Taste and Taste Live at the Isle of Wight. All the other albums are just skulduggery arranged behind our backs by our manager at the time.

In the middle of the blues boom at the time, what made Taste more successful than any other group of the period close to your musical style?

I can’t really say. I think perhaps it’s because we had an original repertoire and that even if our musical register was perfectly situated, it was, nonetheless, difficult to put us in a strict category. On stage, we played 90% of our own music and 10% covers, no more. You can find many influences in our music, from jazz to heavy metal, if you can call the music of that era heavy metal, with many improvised parts. And then, there was often a dose of rebellion in our music that perhaps had an impact on the public at that time. Perhaps my Irish side also transpired in the music. I don’t know because at that time, we didn’t have the time to analyse ourselves. Everything was moving so quickly!

Tell us about your performance at the Isle of Wight.

Everything happened in a relatively confusing way. At that time, we were in the middle of a European tour. One evening in Hamburg, at the end of the show, our manager came to see us and said, “Stop everything. We’re playing the Isle of Wight tomorrow.” We said to him, “Okay.” We threw our equipment into the minivan we had at the time, we squeezed four people into the front, the others in the back, and we left. For us, at that time, the festival was nothing more than just another concert.

Of course, we arrived late and then I saw everybody, all these hippies. I thought that something was going to happen. We got up on stage with rage, a rage to convince, a rage to communicate. Like on stage, we didn’t get along, at first it was tough, but I was screaming and the audience immediately liked it. Then when we did Sugar Mama, a human wave approached the stage and then we unleashed our whole repertoire. The crowd went mad and everything finally went well. Apart from my nerves and emotions, it was one of the best experiences in the life of a musician.

So, why did Taste split up a short while after the show?

There were a lot of problems in the group, human problems that could no longer be resolved other than by splitting up the group. During that European tour before the Isle of Wight festival, I knew clearly that the group was already dead. We no longer enjoyed playing together and the fact that our manager was tricking us according to his will was largely the reason for the group breaking up.

We thought that it would be great to finish with this big festival, even if, just before, we didn’t know the extent to which the Isle of Wight festival would become important in the history of rock.

How does that era compare to today?

To tell you the truth, I prefer the way that things are done today. In that huge excitement of rock music at the end of the 1970s, everything was crazy and wild. I never had the time to reflect, to check what I was doing. It was exhausting in the long run to be always walking on a tightrope. Technically speaking, we had nothing: an amp, a guitar, a few spare strings, and that was it, so we were playing without a safety net. At the Isle of Wight concert, I didn’t hear myself sing or play for one minute. I could very well have been mistaken mistakes throughout the concert without realising it. Today, everything is much more relaxed and I am much better at checking what I do, which enables me to reflect and be more critical.

After the break-up of Taste, you started your own solo career. How was it at the beginning?

After our last concert, there was a certain amount of time needed to sort out the numerous legal problems we had. Then I needed a period of reflection to think about what I was going to do and write new songs. I called an old friend in Cork who was called Wilgar Campbell and who I met in Belfast at a Taste concert because he was playing in the group who opened for us called Deep Joy. It’s Wilgar by the way who introduced me to Gerry McAvoy who became the bassist in my group. Together, we left, we rehearsed and then we did some concerts under our name and we were signed. There you go!

Then we went to Advision studio in London, under the direction of Eddy Offer who had worked with John Lennon’s group, and 10 days later, we had put together our first album.

Without counting the compilations, you have brought out 12 albums to date, of which 3 are live. Which ones satisfy you the most and the least?

Of my 10 studio albums, I am not totally satisfied with any of them. I would really like to remix all my albums, even see about rerecording some songs. I think that all my albums only please me about 60%. For me, making a record is always embarking on a new adventure with a passion that oscillates between love and hate. On every record, there are songs that I love, others that I hate because they haven’t turned out how I would have liked them to turn out now. My favourite albums are Tattoo for the songs, Against the Grain for the production and Top Priority for the professionalism of everything. In terms of the album that I like the least, that’s Blueprint, which I will remix whenever I have the time.

When we see Rory Gallagher on stage, we desperately look for a show. But there isn’t any. Do you not sometimes feel out of place or outmoded by a rock scene that is more and more centred around visuals?

… to the extent that the music is forgotten, by the way! To tell the truth, the look, the show, the lasers, the special effects, all that circus, I want nothing to do with it. Perhaps I will do a video if the record company asks me to, but that’s not my concern. When you go back to the origins, you see that artists like Elvis Presley or Muddy Waters put entire concert halls into a trance simply with their voices or their instruments. I have been to that school and I continue to prefer authenticity rather than playing the fool with a feather in my backside…

[article below from red text box alongside interview]

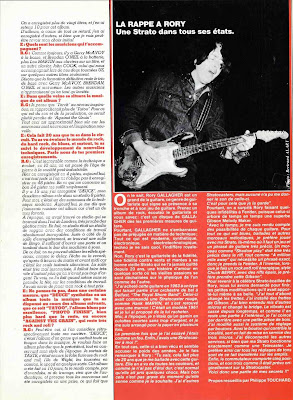

RORY RAP – A STRAT IN ALL ITS STATES

We know, Rory Gallagher is a guitar great, that sort of guitarist who marks his presence with his face and guitar playing. Take a rock album, listen to the guitarist and you know: it’s a Gallagher album from the first sounds of the guitar.

However, Gallagher is not embarrassed by his prejudices towards technology. He is hugely indifferent to everything that is modern, synthetic, electronic, electrotechnological, techno I don’t know what.

No, Rory is a loyal guitarist, loyal through thick and thin to his good old Strat who hasn’t left his side for 20 years, a love story of sorts where old passions are just as much stirred up by the physique of one as the other.

“I bought this guitar in 1963 from a guy who was part of a showband in Belfast ‘The Royal Showband.’ He had ordered a red Stratocaster like Hank Marvin and he had ended up with a brown one! It was a 1961 model and I asked if I could buy it from him. At that time, I was just a young boy in shorts without any money and I arranged to pay for it in several instalments. The first time that I tried it, I was in heaven. Finally, I had my own Stratocaster!”

Anyway, this Strat seems to have lived well and is certainly showing the wear and tear of its age. I said as such to Rory. “Do you know, I’ve been using that guitar for more than 20 years. It has seen all sorts of things and as I don’t have a hard case, it’s taken many hits. But it doesn’t matter at the moment because it sounds just as I like. I have other Stratocaster’s, but none of them give the sound of this one. That’s why I keep it.”

However, we were surprised that Rory was disloyal to his Fender sometimes, as from time to time, he uses a superb Gibson Melody Maker instead.

“Over time, I have realised the possibilities of each guitar. For blues, ballads and other melodic songs, I prefer to use my Strat, particularly when you need a very precise sound and tone. A song like Shadow Play must be very precise on the riff, just like A Million Miles Away, which needs an exact sort of sound, so I use the Fender. However, if I’m doing an energetic rock and roll piece in the style of Chuck Berry, with rough riffs, I prefer to use the Gibson.

To go back to Rory’s famous battered Strat, we asked him to finish by telling us about the small modifications that he has done himself to the beauty: “First of all I changed the frets. I put Gibson frets. I also learnt how to change the other pickups and change the bridge. The vibrato was blocked a long time ago and as there is still a part inside, I have blocked it inside with a piece of wood. I have also modified the tuning system with buttons. In fact, the button that controls tone, is actually used for the three pickups. I disconnected the other ones, so my Strat works exactly like a Telecaster. I actually prefer it because all the tone adjustments are transferred to the amp instead. Finally, the switch has five positions and not three as was the case originally on the Stratocaster. So, now you are privy to my secrets!!

Leave a comment