I cry at what’s become of me

But is it wrong to also feel comfort?

Knowing you felt the same

Somehow without intention

I’ve built my own Conrad Hotel around me

I wrote these sombre lines in my journal on a particularly low day in February 2021 when I hadn’t left my house in over three weeks. After a crippling panic attack alone in the middle of the street in November, I found myself slipping into a lonely world of agoraphobia.

Feelings of intense nervousness and fear have been a daily feature of my life for as long as I can remember and, at the age of 13, I was officially diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, but never had I felt this bad before. I had always been a very active person and loved nothing more than being outside walking and exploring my surroundings. Now, I had no desire or inclination to do anything or go anywhere.

Days would pass without going outside until the point where everything beyond my four walls felt so scary that I just couldn’t face it. I would spend hours standing in my hallway trying to accumulate the mental strength to open my front door. On the odd occasion, I’d manage, only to reach the end of my street and have to turn straight back around because I was gripped with nausea, dizziness, blurred vision and a barrage of other terrifying symptoms. I’d burst through the front door, heart racing, throw myself down on the bed and sob into my pillow at my inadequacies.

As my weeks became marked by the days – or sometimes just hours – between panic attacks, I felt hopeless, lost, forlorn. Lockdown may have come to an end and life was slowly returning to normal, yet mine was becoming increasingly abnormal. The door may have been metaphorically wide open before me, but I was unwillingly tied to a chair, unable to move. I had become a prisoner, yet I was also my own jailer. My body was fighting to survive, yet my mind was trying to die. Sometimes, I thought I would drown in the amount of tears I shed.

Christmas 2020 was absolute misery. It rained non-stop for twelve days. Apart from the 25th, which I spent with my partner, I was alone. All I had for comfort was music. So, while people around the country were sat with their families, eating, drinking and being merry, I found myself spending my Christmas curled up on the sofa in my pyjamas doing nothing but crying and listening to the soothing tones of Rory Gallagher. I’d quickly scrub myself up and paste a smile onto my face just before my partner came home from his long shift at the hospital, hiding my anguish so as not to worry him and reassuring him that yes, my day had been lovely.

Since becoming a Rory fan in 2016, I’ve developed a close connection with him in ways I’ve never felt with any other musician. I see myself in him so much that, at times, it scares me. Yet as I lay there on my sofa with ‘Easy Come Easy Go’ on repeat, sinking further into myself, my relationship with him intensified. “You used to fly and chase the wind, I don’t know you lately.” Those lyrics chilled me with their frightening accuracy. How could Rory have been writing about me back in 1982 when I wasn’t even born until 1991?

As ‘Easy Come Easy Go’ moved into ‘Walkin’ Wounded’ and the lines “I feel suspended, got no lust for life” poured out, it hit me. That was the precise moment. Rory went from being my kindred spirit to me somehow transmogrifying into him. Heart in a sling? Check. Injected and don’t feel a thing? Check. Wounded like a fox in a snare? Check. If I had some sense, I would indeed have gone back to my hometown on the southern coast, at least temporarily, to “feel like a normal human being again,” as Rory said in his 1993 Leeuwarden radio interview. But instead, my house had become the Conrad Hotel.

Rory moved into room 701 of the Conrad Hotel at the beginning of 1993 and lived here for the remaining two-and-a-half years of his tragically short life. His brother Dónal was concerned that Rory had a tendency to become depressed when not touring and was unable to look after himself. The Conrad, therefore, was supposed to provide him with a home-from-home environment that would replicate life on the road and make him feel less lonely. However, it had the reverse effect.

Rory became increasingly reclusive, spending more and more time isolated in his hotel room. He used the pseudonym Alain Delon (his favourite actor) so as to be uncontactable and wouldn’t even let the maid in to clean. For anyone who’s seen photos, Rory’s room was no luxury. Its beige curtains, walls, carpet and furniture look bland and clinical, while its poky size meant that all Rory’s instruments – his prized possessions and life work – were encased and shoved in a dark corner, like a poignant visual analogy of what the music industry and media had gradually done to him throughout the 1980s.

Photographer unknown

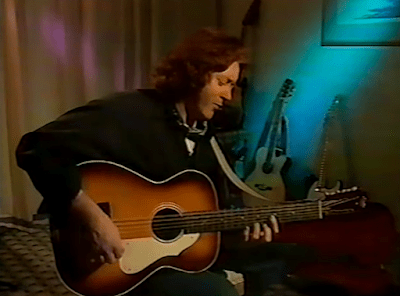

Rory barely left his room or let people in and, when he did, he did so with much fear and trepidation. Guitarist Eric Bell recalls bumping into Rory on Denmark Street looking extremely disoriented and helping him back to his hotel to calm him down, while director Brian Reddon recalls him being “paranoid” and “anxious about everything” when he was interviewed in his room for Ulster Television’s Rock ‘n’ the North.

Every time I see a letter written by Rory on a piece of headed paper from the Conrad, my stomach churns at the thought that he spent so long there alone. I think of how he told friends that his flat had a leaking roof and that’s why he couldn’t live there, of how the hole kept getting bigger every time he told the story to somebody new, of how Dónal had climbed up on the roof and found no hole and of how that hole was actually a metaphor for Rory’s own life falling apart. The story had always saddened me, but as I reread it over the Christmas period, I cried uncontrollably, realising that this was me. Like Rory, I had a perpetual drip, drip, drip that was threatening to flood, overwhelm and sweep me away if I didn’t get it fixed.

Christmas passed and I told myself that it was the start of a new year; things would get better. But nothing changed. I still stayed trapped within my Conrad. Then came my 30th birthday in March, a date that I should have been celebrating in Cork. Things would get better, I said. But again, nothing changed. I still stayed trapped within my Conrad. And with each passing week, I set new milestones. I’ll be better by my brother’s birthday… by Easter… by my niece’s birthday… and so on and so forth. Yet try as I might, I just couldn’t achieve them.

I was reminded daily of the Rory quote “I’m happy as a musician but not happy as a person,” which he said in an interview for Swiss TV, given in his hotel room in summer 1994.Those lines chipped away at my soul. I couldn’t have felt them more if I had written them myself. While I remained trapped within my Conrad, I was still able to somehow perform successfully at work. To my colleagues, nothing was wrong. I delivered presentations, wrote papers, carried out my daily activities and met deadlines effortlessly, just as Rory continued to perform night after night despite his worsening mental and physical pain. I thanked the Lord for the ability to work from home (or at least my employer!), yet at the same time cursed this ability for keeping me in what had paradoxically become both my prison and my sanctuary.

Still from Rock ‘n’ the North documentary

In May, I reached breaking point. I just couldn’t cope anymore. It was starting to affect the relationships around me. None of my family or friends could understand why I didn’t want to see them now that we had freedom to travel once again and especially after not having seen them for over a year. How could I explain when I had spent all my life trying to hide my anxiety? Feeling too embarrassed to speak up, no matter how awful I was feeling. So, taking a deep breath and plucking up the courage, I submitted a self-referral to see a counsellor.

I’ve had counselling on and off for the past 15 years, usually at moments of extreme crisis, and it has always helped. The trouble is that I have a tendency to fall back on bad habits as soon as the sessions stop. But now I was experiencing a crisis like no other and had nowhere else to turn. I thought often of Rory during this time, of how he never got the support he so desperately needed, how he could still be here today if counselling was more readily available back then. It was Rory who gave me the strength to go forward. I closed my eyes and I could so clearly see his tired, sad face looking back at me, but urging me with a warm smile to persevere, not to give up.

I was so nervous on the first day of my counselling (via Zoom thankfully!), having to meet a new person and explain my problems in detail. Imagine my surprise when I logged in and was met by a kindly woman with a strong Cork accent! I instantly relaxed, even smiled to myself feeling that my guardian angel Rory was somehow watching over me. I hit it off immediately with my counsellor and, over our months together, I found myself actually making progress for the first time since that fateful panic attack back in November 2020. Granted, very slow progress, but progress, nonetheless.

With her help, I started to go out every day. Just standing outside my front door at first and breathing in the fresh air, before building up slowly from one minute to two to three. By the third week, I was managing ten minutes outside alone. I felt incredibly sick and my legs were like jelly, but I had my MP3 player charged with Rory interviews and I tuned into his calming spoken voice to help me on my way.

I lacked the confidence to stray far from home, so I stuck to the same circular route, yet gradually built up to repeating it several times until I could last the whole of Cleveland Calling, the whole of the Guinness Masterclass, the whole 1991 Japan interview. Sometimes on a particularly good day, I even managed to sit in the park near my house for a short while. I also began to embrace creative outlets for my anxiety like painting, story writing and poetry – activities I hadn’t done since I was at secondary school.

By June, I had even worked up to seeing my family again. I went to the zoo with my dad on his birthday, out for coffee with my mum on hers and to the city centre with my partner for the first time in 18 months to pick up Cleveland Calling 2 on Record Store Day. I did all these things with extreme anxiety, yet feeling slightly more secure knowing that I was with my loved ones and they could help me should a panic attack happen.

Back in November 2020 – shortly after that debilitating panic attack – I set up an Instagram account dedicated to Rory. What started as a place to just post random photos turned into a fan account to which I now dedicate much time and energy. Social media has many valid criticisms, but it can also be a godsend for some people, especially those like me who are socially anxious agoraphobics! Rory wasn’t part of the social media age and had nothing but his daily phone calls to his mother Mona to keep him company when locked in the Conrad (although to be fair, I don’t think he would have embraced it, at least without some coaxing from Dónal!). But through my Instagram account, I have been able to connect with people all around the world and make many dear friends.

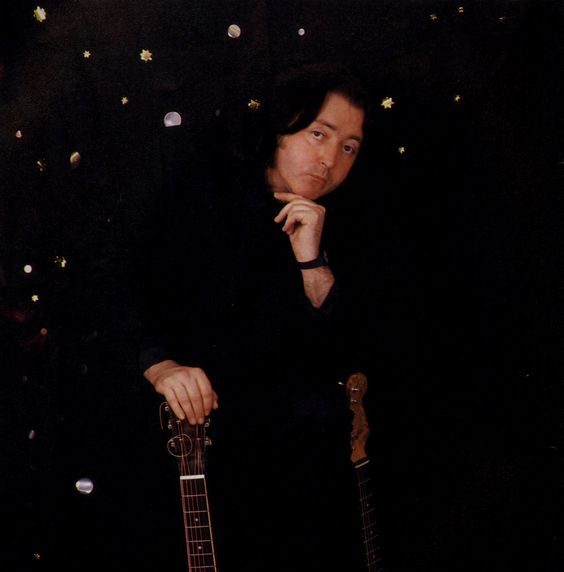

Photograph taken by Rory himself

As I accumulated more followers, I came up with a plan: to use my account, not just as a platform to remember Rory but also to raise awareness of mental health through him. On the one hand, I hoped to tell the truth about Rory’s story, build compassion for him and correct the overwhelming focus on the 1970s in pretty much every other Rory fan account. However, on the other hand, by writing, I hoped it would help me understand myself better, feel happier in my skin, accept and, dare I say, even love myself more. I dearly wish I could go back in time and save Rory from his fate, but given my inability to do this, the least I can do was something positive in his memory to help others.

In my posts, I started to speak candidly about my own experiences with mental health, as well as Rory’s, and how he had helped me so much in all aspects of my life, particularly over the past two years. This culminated with a mental health awareness week that I launched at the beginning of October 2021 focusing particularly on the latter years of Rory’s career. Through my posts, I aimed to show people just how much Rory continued to achieve despite his struggles with depression and anxiety, how he should not be defined by his ill health and how he should be treated with compassion and respect in all eras of his life. I was so nervous about how people would react (especially as responses to Rory’s later years on Facebook have always been rather negative), but the support I received from Instagram followers was overwhelming.

The success of this week gave me a newfound confidence. So, instead of reacting in my usual ‘keyboard warrior’ style to the negative comments about Rory on Facebook when 1994 photos from Nancy were posted, I instead began to think about setting up a positive blog space dedicated to these final years. I decided to call it Rewriting Rory and it would serve as a place of reflection dedicated to rethinking the last his years of Rory’s career, while fostering a friendly and understanding attitude towards mental health. I invited my friend Rayne to join me on the venture and, together, we set out to showcase what an exceptionally remarkable human being Rory was and encourage others to explore the 1985 to 1995 period in more depth. We saw it as our little way of giving back to him for all he’s done for us.

Thanks to Rory, I became empowered for the first time to speak honestly with my family and friends about my problems. It’s amazing what a difference it makes to be open and what a weight it lifts from your shoulders. You feel more in control, you can set your own boundaries and, on the whole, people generally respond with empathy and kindness. And those who don’t, quite frankly they’re not worth having in your life anyway. I have also collaborated with the wonderful Heavy Metal Therapy and have written blogs through my job on the topic of living with social anxiety.

Now over a year since that “panic attack to end all panic attacks”, as I call it, I’m still making very slow progress. Yes, it’s a long road ahead. I still receive counselling. I still have an invisible barrier stopping me from walking any further than I have for the past few months. I still get setbacks. I had three panic attacks on the anniversary of Tom Petty’s death back in October, for example. But I keep marching forward. And gradually, the setbacks and the panic attacks are coming with more space between them, time for me to breathe a little rather than to feel as if I’m constantly hyperventilating.

A major achievement for me was 7th January 2022. After months of psyching myself up and working with my counsellor, I made it to the 1971 Reading Festival exhibition. To my surprise, there was nobody else there and I spent a good 90 minutes alone with Rory’s Telecaster. And there before the guitar, I knelt down and I cried like a baby. To me, that Tele was a physical representation of Rory himself, as if he were standing before me, as close as I could possibly be to him. Amid sobs, I spoke quietly, thanking him for everything and telling him about the journey I had taken to get there today. Before leaving, I patted the glass case affectionately and whispered: “I’m doing it, Rory. I’m tearing down the walls of my Conrad Hotel.” And with that, I left the room, not turning back for fear of crying once more, yet my heart bursting with pride and love for Rory and all he has helped me to achieve.

Lauren, February 2022

Photograph taken by Lauren Alex O’Hagan

Leave a comment